Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films, TV shows, and video games that kept us staring at screens. More from this series

For many people, 2017 was a year endured rather than lived. If 2016 was marked by the sheer immediacy of survival, then that sense of heightened awareness led us to wonder just how the fuck we got to where we are now. As reality continued to morph into the cartoonishly hyperreal landscapes of a nightmare, the cinema of 2017 brought forth a much-needed wave of pragmatism, forcing us to take a long, hard look at our collective histories — both recent and long ago, historical and fictional — as a means of regaining our bearings in a world where the rug had seemingly been pulled out from under our feet.

Whether these films were tackling issues of race (Mudbound, I Am Not Your Negro), sexuality (BPM, Call Me By Your Name), or even our youthful connection to the towns we grew up in (Lady Bird), there was an urgent sense of gazing back in time to reckon with our mistakes. And these contemplative reevaluations wisely skirted pure nostalgia, paving the way for thrilling narrative and visual experiments, from slowly peeling back the perfectionist veneer of the 1950s London fashion world to reveal its psychological kinks (Phantom Thread) and extolling the humor and wit of a reclusive poet (A Quiet Passion) to examining a collision between personal obsession and imperialism (The Lost City of Z) and a daring retcon of the world’s most ubiquitous film series (Star Wars: The Last Jedi).

Even topics that have been long since rendered inert were made exciting once again in 2017. Christopher Nolan’s use of World War II (Dunkirk) as an experiment in crosscutting and tension-building and Albert Serra’s wry Renaissance-painting-come-to-life (The Death of Louis XIV) displayed new aesthetic strategies for representing and grappling with the past, while James Franco used the behind-the-scenes on-set comedy (The Disaster Artist) to explore both the authenticity of our attachment to so-bad-it’s-good cinema as well as the emotional and economic intricacies behind its own making.

But where many films looked behind us, there were still plenty drawing inspiration from the urgency of our current and near-future predicaments. Some of our favorites managed to touch on the potential repercussions that technological advancements will have on our consciousness and memory (Marjorie Prime) or our sense of self-worth (Ingrid Goes West), while others remained firmly grounded in the struggle to simply exist and make it to the end of each day (The Florida Project, Good Time). These 30 films demonstrate that the art of filmmaking can still be emboldened by sociopolitical turmoil to re-examine its own means of production, simultaneously breathing new life into once-stale forms and breaking boundaries to create new ones.

30

BPM

Dir. Robin Campillo

[The Orchard]

If the personal and the political are inseparable, then so too are life and death. Robin Campillo kept these stakes entwined at the front of BPM, emerging with something miraculous: a film about unimaginable tragedy that makes every effort to assert humanity. Set within the Paris branch of ACT UP in the 1990s, BPM followed a cluster of young activists — largely HIV positive — fighting not only to be visible in the public eye or tolerated as part of French culture, but also to create actual, tangible change. Campillo made clear that, in this world, political action is not optional: these characters were fighting, quite literally, to save lives. The film’s genius was in building these lives to their full complexity — whether the bliss of the club, the joy of belonging to a community, or the pain of watching the person you love pass away. Much more than a sober, “important” film, BPM was fully alive with all the contradictory truths that life embodies, including death. To paraphrase one character’s eulogy of another, it was a film that lives these truths, beautifully, in the first person.

29

Nocturama

Dir. Bertrand Bonello

[Wild Bunch]

Is radicalization without a political agenda possible? Bertrand Bonello’s latest film Nocturama explored such an idea, a thriller with no time for ideology but all the more provocative for it. Indeed, the homegrown terror attacks it depicted were executed by a group of French youths with no unifying purpose, not even a common cause for complaint. The bombings and murder were a simple product of teenage ennui. Or so it seemed until the film’s second act. After a meticulously coordinated execution resulted in chaos-unleashing attacks all over Paris, the teenagers took refuge in an upscale department store. Ostensibly waiting for their reckoning, they watched TV reports of their actions with little interest. No revolutionary proclamations were issued or contingency plans for the attackers to escape outlined. Instead, they donned designer clothes, drank expensive wine, and blasted “Whip My Hair” on high-end stereo systems. Then we realized these French teens couldn’t possibly rise against the only system they knew. They couldn’t survive outside of it, so they chose to end their lives as perfect citizens of it as they could. Subversion and consumption have long been reduced to the same process, terror redefined as the ultimate consumerist temper tantrum, the wildest of animals a neatly displayed part of the spectacle.

28

Ingrid Goes West

Dir. Matt Spicer

[NEON]

The ultimate joke behind Ingrid Goes West, Matt Spicer’s on-the-nose stalker comedy for the iPhone age, is that as much as we might want to see the film’s gaudy SoCal personalities as caricatures or view its characters’ relentless social media dependence as blown out of proportion, the truth is that the movie pretty much told it exactly like it is. As we watched social-media addict Ingrid Thorburn (a never-better Aubrey Plaza) pry her way into the personal life of minor Instagram celebrity Taylor Sloane (Elizabeth Olsen, fake to perfection), it might have seemed like Thorburn’s sociopathic road to destruction lay outside the realm of what a sane person would ever do. But the horrifying reality, of course, is that privately stalking one another has become a normalized facet of our society, and depending on the reassuring approval of strangers is how our entire generation has been taught to value its self-worth. Of all the film’s insufferable, narcissistic characters, not one of them didn’t directly remind me of somebody I know, their food hashtags so painfully familiar, their insistence on calling each other their “favorite person ever” like an emoji knife straight to the gut. But most harrowing of all was the simple image of Ingrid, sprawled out on her couch, trying to find the perfect response to a comment, re-typing her reply over and over again, each “haha” a desperate, maddening cry to be loved.

27

Okja

Dir. Bong Joon-ho

[Netflix]

Any kid who grew up on a farm will tell you that pigs are smart, friendly creatures, more pets than meat products. At least until they end up on the dinner plate. Bong Joon-ho’s Okja took this macabre piece of folk sentiment and crafted it into a darkly fantastic fairy tale about cross-species friendship, radical activism, and the agricultural-industrial complex. While this may not have been the classic Spielbergian formula nostalgists were seeking from a film like this, the friendship between a young Korean farm girl (Ahn Seo-hyun) and the giant, genetically modified pig creature of the title was ironically among the most honest human relationships of 2017. Of course, it helped that the actual humans in this film included Jake Gyllenhaal in his most natural state of twisted glee, two Tilda Swintons, and Paul Dano at the radical edge of sincere bro activism. The nightmarish final sequence in the slaughterhouse may have been disturbing, but if you ask us, that was kind of the point. The sole purpose of art isn’t necessarily to make us feel good about our place in the world.

26

The Lure

Dir. Agnieszka Smoczynska

[Janus]

A real event movie, a total spectacle that careened from gritty violence to pop culture gloss, swaggering through multiple genres, Agnieszka Smoczynska’s The Lure tackled the latest incarnation of the battle of the sexes from a totally unexpected angle. Golden and Silver were a pair of innocent/feral mermaid sisters who got dropped into the thick of the politics of exploitation when, fresh from the river, an old barnacle put them onstage at his cabaret/strip club. Using fishiness as a metaphor for female power, identity, and sexuality, Smoczynska created a brilliant portrait of what male fascination, fear, disgust, and desire look like from a woman’s perspective. She took men’s bad behavior as a given; far from rolling up her sleeves with an American determination to correct the problem, the question she posed was whether to love men anyway — risking self-annihilation — or kill them. Golden and Silver embodied the two options, and their adventure living amongst humans, punctuated with pop song and dance sequences and populated with rich and vivid characters, was gorgeously shot, provocative, wise, and dangerously fun.

25

Baby Driver

Dir. Edgar Wright

[TriStar]

Total, idle speculation here, but it seems pretty apparent that Edgar Wright is what we in the biz like to call a “fan of music.” Giving a film a memorable soundtrack is one thing. Choreographing an entire film to its soundtrack, making sure every scene down to individual sounds like gunshots or squealing brakes sync up, is another thing completely. But that’s just what Edgar Wright did with Baby Driver, a film that managed to take his already apparent love for memorable scenes set to music and *checks exhaustive list of car terms* shifted things into fifth gear, remembered to signal before turning, and burned all the rubber with it. From rock to soul to hip-hop to one very specific Simon & Garfunkel song, music breathed a frenetic energy into the film, which returned the favor in kind. Whether a climactic chase set to “Hocus Pocus” or a casual coffee run to “Harlem Shuffle,” everything felt original and exciting. On a sound editing and design level alone, Baby Driver had few equals in 2017. And as a ridiculously fun and tense entry into the heist/car chase sub-genre that managed to pay homage to its forebears, while also carving out its own spot among them? It was certainly unmatched there, too.

24

Mudbound

Dir. Dee Rees

[Netflix]

It’s World War II, and America is a golgotha. The sky is somehow more civil. Folks speak in poetry. Rees’s historical epic achieved much in its short length; it was an unflattering portrait of hard-luck white America reminiscent of Faulkner or Steinbeck (all the way down to its many epistolary narrations, shared across racial lines), a complicated tale of surrogate brothers united by trauma rather than skin color, and a hymn for how black Americans continue to endure the specter of slavery. Now, crack all that open, and there was still more to gain — the brutal dangers of being “well-meaning,” some even-handed symbolism that illustrated the racist thought of black sexuality/assertiveness, and the strained stubbornness of masculinity. Crack all that further, and, yeah, you get it. Mudbound reclaimed the American historical epic film as something needed to be retold with enormous tact and sensitivity, to let subtlety and dignity persist amongst the infertile soil and filthy, oppressive air. Having a firebrand ensemble — through Mary J. Blige, Carey Mulligan, Jason Mitchell, Jonathan Banks, etc. — to grace the Delta and give it proper due didn’t hurt either.

23

The Disaster Artist

Dir. James Franco

[A24]

“Oh hi Mark.” The Room was considered the best worst movie ever made. It featured cringe-worthy acting, conversations that went nowhere, superfluous plot points, and lots of gratuitous sex. There’s also a scene wherein characters play football in tuxedos. This monstrosity also somehow cost six million dollars to make, yet has earned a rabid cult following since its 2003 release. This year, James Franco decided to pay homage to the production by casting himself as the director and lead actor in The Disaster Artist, based on actor Greg Sestero’s published account of the original production. Sure enough, the film revealed The Room as the obvious shitshow it was. Still, The Disaster Artist pulled off being uncannily enjoyable and legitimately funny. Franco also brought a human element that was absent in the original: two actors, bound by pact, struggling to get their vision noticed. If nothing else, you’ll see the original in a whole new, bizarre light. You’re tearing me apart Lisa!

22

Antiporno

Dir. Sion Sono

[Nikkatsu]

There are not enough trigger warnings on Earth for Antiporno. Sion Sono’s contribution to Nikkatsu’s reboot of its legendary “roman porno” line was an exhilarating (and exhausting) mess of smut that spazzed between high and low class before rocketing into outer darkness. What started as a passion play of artist-and-assistant sadism very quickly went into the weeds — while our lead, Kyoko (Ami Tomite, incredible) flew between multiple personalities (…or does she?), trading lives and power roles with the equally game Mariko Tsutsui. As Sono destroyed every primary-colored fourth wall he could get his paws on, the film’s own inconsistency became its compass. Roles changed within minutes, within shots, to the point where — like Kyoko herself — nothing was reliable. Is it an autocritique of porn? Filmmaking? Men? Women? Personal freedom? Everything? In its t&a, fluid-drenched indifference to taste, Antiporno might seem either liberating or repulsive to the viewer. It’s unclear which reaction Sono and his collaborators might prefer — what is clear is that film would probably most prefer to scream at you until it falls down in a pile of its own puke.

21

It Comes at Night

Dir. Trey Edward Shults

[A24]

One of my favorite moments in post-apocalyptic stories is when the characters come across a wrecked house in search of supplies and stumble upon the decayed corpses of a longtime dead family. This recurring motif always leaves me eager to know more about that grisly situation. Thus, my more than pleasant surprise when Trey Edward Shults’s It Comes at Night explored my enduring obsession with a refreshing take on the post-apocalyptic genre, concentrating the action entirely within a single setting and the slow turn of events leading to the characters’ inevitable ruin. The confined post-apocalyptic story was a risky bet, moving away from the immediately recognizable grandiose scale of worldwide collapse and focusing instead on the tensions between two desperate families. However, the film’s claustrophobic domestic environment and the persistently unsettling feeling of dread created a mesmerizingly bleak experience, wherein the end of the world gives us no heroes, no safe shelter, and nowhere to run except to our own anxieties and fears, which always seem to sneak their way into our nocturnal nightmares. That we are our own worst enemies may not be the most original idea in a post-apocalyptic drama, but It Comes at Night found its own unique approach to explore the gradual deterioration and mental breakdown of the unknown, ill-fated post-apocalyptic survivors.

20

The Meyerowitz Stories

Dir. Noah Baumbach

[Netflix]

Noah Baumbach has been making great films for well over a decade, and The Meyerowitz Stories might be his best. Taking the humor and pathos of his earlier films and entrenching them in a thoroughly modern and relatable story of family pathology, Baumbach offered up a delightful, affecting film here. The best commentary on The Meyerowitz Stories comes from one of its stars, Dustin Hoffman, in an interview with Jimmy Fallon: “It’s basically about a family that doesn’t have religion, but substitutes it with art. And I’m a sculptor who never became as successful as I wanted to be, and these guys suffer because of it… I think what I did to them is what many fathers do to their kids, is they signal them nonverbally not to be better than he is. In other words, not to have more success than the father does. Don’t surpass them.” Hoffman then asked the audience if they could relate to this, and there was a deeply uncomfortable silence. That’s Noah Baumbach for ya.

19

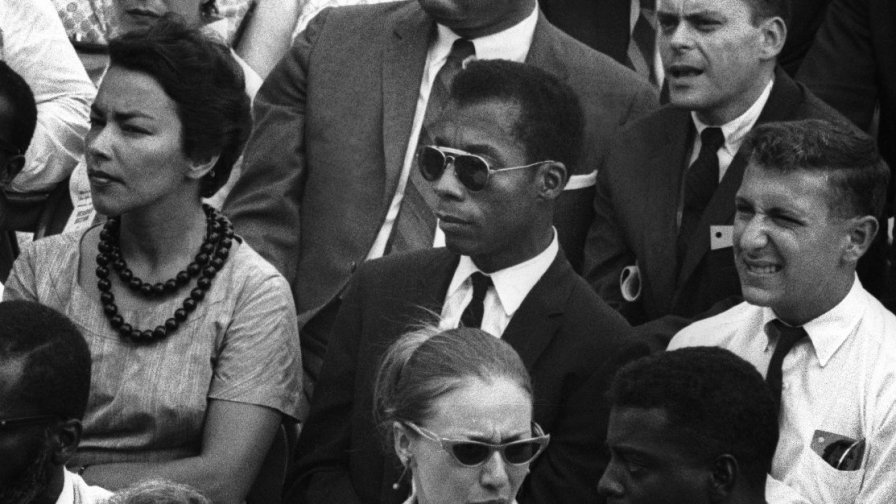

I Am Not Your Negro

Dir. Raoul Peck

[Velvet]

From across the ocean, the history of racism in America always seemed somewhat surreal. Not that racism didn’t exist here, but that the recent history of black struggle in the US was a history of abuse institutionalized to the point of being, as many argue, an integral part of the state, the founding lie of a country claiming freedom as synonymous with it. Raoul Peck told the story of the struggle against that lie through the words of James Baldwin, but it was not a poetic narrative, if poeticism implies detachment from material reality. It is a very personal archive of violence recorded in historical facts, wounds as much private as they are public. By using footage from current events alongside archival recordings, Peck forcefully reminded us that those wounds are still open; more than that, new ones are still collected and ever more blood is spilled. Baldwin’s words become prophetic, but it is a prophecy of Afro-Pessimism, of hopelessness in the face of a world built on exclusion, of anger with no agency to force a change through it. At the end of the film, we were left with a feeling that what Frank Wilderson was saying for years is perhaps true: that this world needs to be torn down in order to open the possibilities for true change.

18

Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi

Dir. Rian Johnson

[Walt Disney]

Let me paint you a picture of the future. Do you remember that movie you loved from the time you were a child? The one you’ve watched so often it’s become a part of you? Hollywood is going to keep making that movie. Again and again, you’ll drag yourself to the theater, chasing the dragon of that wonder you felt all those years ago, but you’ll leave feeling a little emptier every time. This will go on until you die, and then it will keep going on. Forever. The reason The Last Jedi resonated so deeply with some fans and alienated so many others was because, for a bracing two-and-a-half hours, the film posited an alternative to this future. Rian Johnson refused to cater to his audience’s expectations. Traditions were torn up. Old heros were cast in a new light. Black-and-white moral frameworks were shot through with new shades of gray. The resulting film was flawed, unruly, but it offered something we haven’t seen from a Star Wars movie in a long time: the promise of something different from everything that’s come before. Kylo Ren instructs Rey, “Let the past die. Kill it if you have to.” It’s a motto we wish more film franchises would take to heart.

17

Marjorie Prime

Dir. Michael Almereyda

[Passage]

Memory is messy business. As Tess, slumped over the piano, explains to a slowly pecking Jon, “It’s always getting fuzzier, like a photocopy of a photocopy.” It’s malleable and imperfect as storage, and it terrifies me that so much of my self is constellated around these progressively fuzzier fictions. One day, that self will stretch out into an undifferentiated, gray senility, each instant a dull ache of failed recognition. I saw an acknowledgement of that fear in Marjorie Prime, but also a form of rescue. By way of the Primes — AI-driven holograms of loved ones designed to behave as they did — we can record ourselves and confront our histories, make revisions and rediscover the lost. In talking with the Primes, we converse with ourselves, fashioning the AI as we want it to be, seeking within its generative algorithm the source of our lack, of our doubt, of our grief. Heidegger conceives of technology as a way of revealing truth and the Primes enact a form of rehumanization, bringing us closer to ourselves, drawing from our depths the humanities we have lost from forgetting, be it by effort or accident. In them, there is an archive of the human and of all the concomitant relations. It’s a melancholy notion, being absorbed into the AI, reducing your complexities down into the stream of electrons coursing on the surface of a chip, but, as the film’s close demonstrates, buoyed by Mica Levi’s tender and melancholic score, the work of becoming human persists even after death, as long as the memories are still there.

16

Dunkirk

Dir. Christopher Nolan

[Syncopy Inc.]

In a cultural landscape so utterly consumed with the latent mythos of unchecked nationalism, Dunkirk was a movie we should all have been wary of. Watching the unimaginable horror of generational genocide through the lens of high-budget action setpieces, in which a real-life pop superstar plays a principal role, could be rightfully characterized as “distasteful,” but as far as hegemonic Western war narratives go, Dunkirk was surprisingly considered and inventive. Nolan is gifted as a craftsman of cerebral blockbusters, but with Dunkirk, he tackled his subject with the kind of visceral emotionality he normally struggles to tap into, offering a particularly poignant rebuke of that timeless tendency to dispassionately stitch human sacrifice into the fabric of charismatic jingoism — a thematic thread that could double as an interrogation of the director’s own legacy. It had its flaws of course, but however we problematize it, Dunkirk had the restless contradictions of wartime broiling in its soul, ringing with a special relevance in an era of perpetual, abstract violence from unseen aggressors and a bloodthirsty ruling class giddy with imperialist ambitions. Indeed, with Dunkirk, our historical and cultural tropes shot back.

15

The Lost City of Z

Dir. James Gray

[Amazon Studios]

One of the major films of 2017 to inspire longing for mid-budgeted cinema — nothing too expensive, nothing too cheap — The Lost City of Z was the kind of epic that acknowledged the exoticism and condescension of exploratory, globe-scaling films. Did the problem of the male gaze get fixed? No, but Gray still knew the century in which we live, one where tactile ventures and the willingness to get one’s hands grubby, regardless of race or gender, remained essential. Gray’s big green adventure presented Percy Fawcett as a stolid dreamer, an artist at heart, whose objectives became rigid and unambiguous: to seek within a maligned civilization something worth more than rubber or black gold. The trees moved with the river, while fire roaring against black night became as sumptuous as the elegant interiors. As Fawcett, Hunnam was controlled ambition, never to be as intriguing as the scenery, the sweat, or the support around him: Robert Pattinson as a somewhat reluctant companion (“The jungle is hell, but I kind of like it”), Sienna Miller as Percy’s sturdy wife/collaborator, and Tom Holland as their eldest son.

14

The Death of Louis XIV

Dir. Albert Serra

[The Cinema Guild]

No false advertising here. Albert Serra’s latest gave you exactly what it says on the tin: two hours of the Sun King dying, slowly, in bed. Rather than a tedious terminal longueur, however, The Death of Louis XIV was a marvelous microcosmic synthesis of form and content. It mined the particulars of France’s longest-serving monarch’s protracted death from gangrene to reflect upon the sycophantic spectacle of 17th-century regality and the Cartesian turn to science and reason that would challenge the reign of superstition and ultimately lead to the Age of Enlightenment. By focusing on the corporeal reality of Louis XIV’s decline, Serra stripped the king of his monumental vanity and obliquely addressed the era’s wavering faith in divine right, monarchical absolutism, and the sovereign soul. In this regard, it recalled Jim Crace’s novel Being Dead, while its existential depiction of the stubborn agony of endurance put it in conversation with The Turin Horse. Much of the film’s power derived from Jean-Pierre Léaud, whose own gilded career lent The Death of Louis XIV evocative metatextual resonance; few actors have grown up onscreen the way Léaud has, and the stasis of his riveting performance formed a poignant bookend with the iconic freeze frame of The 400 Blows.

13

A Quiet Passion

Dir. Terence Davies

[Music Box]

Terence Davies’s A Quiet Passion was welcome evidence that artistic innovation and the biopic genre are not, in fact, mutually exclusive. Even more surprisingly, it was proof that a period piece about Emily Dickinson could also be humorous and light on its feet. Lilting timbre and light yet elegiac tone coalesced beautifully in the film’s examination of poetry vs. piety, pitting stoic witticisms yearning for freedom against the unflappable rigors of a staunchly puritanical society. Davies’s visual flourishes reached the heights of his greatest works, particularly the 360° pan in the parlor and the morphing scene that used slow zooms and subtle CGI to transition through decades of time in mere seconds. But as stunning as A Quiet Passion was to look at, verbal language was at its forefront, with wit and relentless philosophical inquiry functioning as armor protecting Emily and her sister from morally righteous clergymen, as well as from the social restrictions and expectations put on women in an era when their independence was seen not simply as an affront, but a direct threat.

12

Personal Shopper

Dir. Olivier Assayas

[IFC]

There were so many things happening simultaneously at any given moment in Personal Shopper it feels like a ludicrous task to distill it all within a single paragraph. Navigating between ghost story, crime thriller, and existential drama, Olivier Assayas’s latest masterwork was a genre-bending exploration of one woman’s personal pursuit of her own identity — an ultra-cool formal experiment into the cinematic art itself — and, of course, a mesmerizing, career-defining performance by Kirsten Stewart. Assayas’s sharp filmmaking skills never allowed Personal Shopper to slip into a vague and insipid formal experiment, having instead crafted one of the strangest, most undefinable, and moving moving films of 2017. Booed at its initial screening in Cannes while praised as a modern masterpiece by others, to say Personal Shopper was divisive is quite the understatement. While distant from anything resembling a crowd-pleaser, there were few films in 2017 quite as daring, idiosyncratic, or relentless in its effort to push the boundaries of the cinematic experience. If nothing else, Personal Shopper was worth it alone for what may be the best texting scene in the history of cinema.

11

Call Me By Your Name

Dir. Luca Guadagnino

[Sony Pictures Classics ]

Call Me By Your Name was a gorgeous ode to the powerful intoxication of infatuation. It spanned its dizzying highs and soulwrecking lows, and did so with impeccable precision. Luca Guadagnino’s film (based on a script by James Ivory, from the book by André Aciman) was a feast for the senses, traversing the incredibly specific time, place, and circumstances of its tale of love in order to become a universal story about discovering oneself in the reflections of another. Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer were excellent, playing characters at different stages in life but who both knew themselves and what they wanted. Michael Stuhlbarg too delivered an epically powerful performance as the intuitive and loving father who watched his son cope with defining his identity amid other emotional turmoil. Call Me By Your Name was devastating in its beauty, precise in its depictions, and wholly affecting through the use of sight, sound, taste, and everything else — a bittersweet memory shared with an audience.

10

Raw

Dir. Julia Ducournau

[Focus World]

Raw, the first feature film by writer/director Julia Ducournau, told the story of Justine (Garance Marillier), a young vegetarian forced to eat meat during a hazing ritual at veterinary school. From there, Justine developed an insatiable taste for other types of meat, including — you guessed it — human. But Raw never felt like schlocky exploitation. It was like Cronenberg doing a coming-of-age story, like Haneke exploring sexual awakening. After the film’s first half built subtly and meticulously to its inevitable climax, the second half shifted to an incredibly articulate exploration of the complex dynamics of sibling relationships. This would not have been possible without the dueling performances of Marillier and Ella Rumpf, who were alternately menacing and endearing. Cannibalism, body horror, New French Extremity – these weren’t new concepts, but Ducournau employed them sparingly and interestingly enough to keep the film engaging and unsettling. Raw was an accomplishment, a film that was gross, funny, sexy, and unnerving, but most of all cohesive. It never felt like it bit off more than it could chew.

09

Blade Runner 2049

Dir. Denis Villeneuve

[Warner Bros.]

It’s unfair and ultimately pointless to demand that artforms defend their existence — but it sure can be a lot of fun. Pretending we’re assholes for a moment: if we were to put this kind of onus on film, what would it have to say for itself? What facet germane to this particular mode of expression is compelling enough to delineate cinema from theater or from literature? While spectacular optics spring immediately to mind, the locus of a film’s singular gravity lies squarely within its ability to impart tone. Cinema can exude this stuff like no other, and here at TMT we always perk up when someone releases a film that is almost entirely bound up with tone. Blade Runner 2049 was so thoroughly imbued with atmosphere it beleaguered the senses, and we demanded repeat viewings just to make sure we could take it all in. All that being said, what made this movie so uncomfortable for us was its underlying theme of parentage. Every significant action in this film was driven by a desire to have been wanted/birthed by something with a vested interest in you thriving outside of the womb, artificial or otherwise. The entirely visceral grounding of this altogether virtual story was what made it equal parts terrible and sublime. It’s probably a long shot to dream that Villeneuve will make another entry into the canon of Scott’s dystopian franchise, but even androids can dream. OH COME ON LET ME HAVE THIS ONE JOKE.

08

The Shape of Water

Dir. Guillermo del Toro

[Double Dare You]

Like a dream like a miracle: in winter, we walk on water. There’s an ice and a concrete and in between, the semi-melted universe, the drops and beads and lines of dreams. The sole can kiss these shapes. A kiss can send the once ice running away or induce a rushing back to hug my print. On water like in dreams, we try not to slip. We try not to fall. The miracle of water is how it welcomes bodies; the shape of water is the motion of care. Like a dream like a miracle, The Shape of Water lives in betweens, a dream of caring to care. A fable of connecting and keeping tight hold of what keeps us whole and healthy, The Shape of Water was Guillermo del Toro’s cool balm on cinema’s lips, the thaw of “emotion is the new punk.” Every life begs care. A dancer testifies, an artist yearns, a scientist testifies, a God loves like man and a man makes himself monster. “I speak your name in my every prayer,” the film promised, and we, bonded like hydrogen, spread around its edges to sip love like water. Like a myth’s memory or a half-thawed poem, The Shape of Water let us live in its love like a dream, like a miracle. We slip, we fall, we sink. We love.

07

mother!

Dir. Darren Aronofsky

[Paramount]

Darren Aronofsky’s thrilling and divisive seventh feature was many things: a Biblical allegory, an environmental screed, an artist’s mea culpa, a comedy of manners, a horror film of intrusion. Most of all, however, it was something that simply doesn’t exist in Hollywood anymore: a mid-budget film in wide release from a major studio, written and directed by a name filmmaker and starring A-list performers, with the gall to be absolutely unabashedly capital-B Bonkers. Give credit to Paramount for putting its money and weight behind what was clearly destined to be one of the most polarizing films of the year. Marrying the aesthetic of Black Swan with the thematic concerns of Noah, mother! was a richly polyvalent and thoroughly metamodern cinematic text that, like The Fountain before it, boldly recombined elements of Judeo-Christian, Mayan, Buddhist, pantheistic, and other mythologies into something that, in its own words, “means something different to everyone.” Aronofsky may have elucidated his intention to tell the story of Gaia as suffering housewife, but that doesn’t mean mother! did not also reflect, consciously or subconsciously, Aronofsky’s perspectives on art, fame, ego, or obsession. A daring, singular achievement from one of our most exciting filmmakers.

06

The Florida Project

Dir. Sean Baker

[A24]

The most important and growingly essential takeaway here is that we take the pressure of message off of a narrative. Strong characters and a strong story are message enough, and are suited to deliver it in a richer, more memorable way. In a largely dismal cinematic year littered with self-satisfied sourness and condescending inanity, The Florida Project’s raw character study was a much-needed blast of AC. Despite the exclusive use of direct cinema style, the film worked like a Gravity-caliber transportive experience. The brisk pacing and vivid milieu of Moonee’s free-roaming, learnedly unscrupulous perspective was so harrowingly and idyllically immersive that one could forget Jesus was there, just barely keeping the whole hot-pink flamingo and pedo-flanked motel ecosystem from falling apart. He and his relatively amateur co-stars managed to both stay out of their own way and keep their fast-deflating balloon scenario aloft. They went with an escapist ending, sure. But, appropriately, it felt like one that Moonee and her friend could’ve chosen: that leap just over the chasm, when we thought all hope was lost. In this pastel hell, no friend to conventional wisdom, we looked down — senses flooding — and took it all in.

05

The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Dir. Yorgos Lanthimos

[A24]

When Barry Keoghan (Martin) auditioned for The Killing of a Sacred Deer, he said director Yorgos Lanthimos had him bounce a tennis ball off the wall and repeat phrases from the script so the natural emotional response to the meaning of the words spoken would dissolve. On paper, this seems counterintuitive for a movie about — to name just a handful — death, guilt, revenge, justice, fate, acceptance, and sacrifice. But when a movie’s most memorable scenes — and we mean this in the best way — consist of an epiphany about eating spaghetti, the awkward gifting of a pocket knife, comparing body hair growth, refusing to let one leave until they’ve tried the tart, or making sure the plants were watered even while bedridden and bleeding from the eyes, we know we’re watching something special. Full of contradictions that shouldn’t have worked but did so especially well, Lanthimos gave us what was essentially an adaptation of the Greek myth of Iphigenia in the guise of a thriller wrapped up in a black comedy. Leave it to Lanthimos to make a story that’s thousands of years old feel not only relevant to our lives, but new.

04

Lady Bird

Dir. Greta Gerwig

[A24]

I threw myself into bed while on the phone with my best friend after seeing Lady Bird for a third time, saying, or screaming, “I just think Lady Bird is an insanely generous movie.” What I mean is what Sister Sarah Joan asks while talking with Lady Bird about her college essay. “Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing? Love and attention?” I mean how wildly and obsessively Lady Bird has decorated her room. Handmade flyers and riot grrrl ephemera. The bright white sneakers Julie wears. How she tells Lady Bird that some people aren’t born happy while crying on prom night. The ribbon Jenna wears tied in her ponytail. The moment Lady Bird glances into Kyle’s living room and sees his dad sick and passed out on a Sunday afternoon. How Lady Bird’s mom stays awake until god knows when sewing a Thanksgiving dress. Like Shelly says, she has a big heart. I think Greta Gerwig does too. She gave each character room to be complicated. Room to fight and forgive and cry and yell joyfully. Room to be messy, room to be everything. This is why I saw Lady Bird so many times: it was generous, sensitive, and so deeply, beautifully human.

03

Good Time

Dir. Josh Safdie and Benny Safdie

[A24]

As it turns out, nobody had a good time in the Safdie brothers’ latest film. Their New York was one of back alleys and dimly lit public buildings, a claustrophobic playground for the city’s petty criminals and collaterally damaged bystanders. But what separated Good Time from boilerplate “murky” crime dramas was an inescapable, lingering tension in the air, deployed almost straight from the off. From the bail bonds shop to a theme park by night, moral ambivalence quickly atrophied into outright depravity as Connie (adroitly played by Robert Pattinson) attempted to free his brother Nick (co-director Benny) by any, and every, means that his deranged mind could muster. In a breathless chain of events, the pure and the damned were entangled in his sadistic schemes; robbery, kidnapping, beating, and drugging a security guard until he was reduced to a babbling corpse. For the breadth of cinematic detail here, the Safdies never lost sight of the terse, gritty action necessary to undergird it all. Perhaps I am mistaken; by the film’s relatively serene denouement, it seemed like a good time was had by observing the wreckage.

02

Get Out

Dir. Jordan Peele

[Universal]

“‘Get Out’ is a documentary.”

– Jordan Peele

“If I could, I would have voted for Obama for a third term.”

– Bradley Whitford as Dean Armitage

It’s not so much argument as it is fact: Hollywood’s productions have seen drastic improvements, as they have more and more embraced the voices of young, black writers/actors. Get Out was a blazing emblem of this truth. Jordan Peele’s debut played — as so many terrifying classics do — off commonplace social norms and strata. But this masterwork took dry, poignant jabs at the audience for even noticing its swarming gags. Did you just laugh at that? Why? You chewed your nails at the sight of that police car? How come? Each character drawn in this antagonizing portrait of white malevolence embodied a different facet of a real-life white supremacist world, wherein the most soft-spoken and faux-well-meaning are the most nightmarish. Get Out’s stunning acumen reflected a reality scarier for us all, even scarier than the movie itself. And that’s saying something.

01

Phantom Thread

Dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

[Focus Features]

In a year wherein bad punditry became the house style of American life, Phantom Thread was a sublime tonic, a reminder that even our most transparent interactions are freighted with consequence, ripe for misinterpretation, and inevitably shrouded in mystery. Much of Paul Thomas Anderson’s film was confined to a single set — the luxurious yet cramped ivory-toned confines of the dressmakers of London’s House of Woodcock — and it was defined by the uncanny, cosmic distance that prevails even among those in the throes of obsessive love. In the most chaste but strangely sexy and undeniably kinky of ways, Phantom Thread charted a path out of the madness love and ambition impose upon us. How do you find comfort and safety in a person you can never know completely? To borrow a phrase by Lesley Manville’s Cyril Woodcock, “The answer to the question is sincerity.”

Phantom Thread was dizzyingly rich on a technical level. Jonny Greenwood’s sprawling score was a dexterous marvel, drunk on Debussy and Guaraldi and flaring with stray notes of dissonance. Anderson’s photography had a similar mix of grandeur and grace, as it peered up spiral staircases and, in one dazzling flourish, circled a dress by Daniel Day-Lewis’s Reynolds Woodcock with a reverent air of surgical quietude. The film was set in the 1950s, but it looked like a product of the heyday of Merchant Ivory Productions: its colors and textured were muted but ravishing, its fabrics and furnitures extraordinarily tactile, its fireplaces crackling and casting the most loving glow on Vicky Krieps’s Alma, the young waitress and blushing ingenue who disrupted and then consecrated the fussy routines and exacting manners of the House of Woodcock. Reynolds’s constant cravings for concentration and solitude were undermined by some truly hilarious foley work, which transformed the scrape of a knife on a piece of toast into an affront of seismic proportions.

Every element of Phantom Thread’s production served to enhance its characters, and Alma, Reynolds, and Cyril were incandescent creations, three poles of equal significance in a love triangle as thrilling as it was deeply weird. The result — something like a chamber drama that doubled as a screwball comedy bedecked with elegant fashions and bountiful platters of pastries — was an expansive discourse on creation that also had a fetish for breakfast and an alternately comic and tragic air of impending doom. It was at once totally concise as a study of how to make a life out of the things and the people you love, and utterly inexhaustible as a scrutiny of the constantly shifting power dynamics innate in being your true self while attempting to live with the people you owe your identity to.

While the film was full of games, confrontations, and ultimatums, every divine utterance in Anderson’s screenplay (“There’s an air of quiet death in this house, and I do not like the way it smells.”) seemed to emerge from a place of utmost sincerity. This is what made the film so beguiling. Like a Hitchcock film, Phantom Thread was endlessly rewatchable, impeccably designed to be approached from the perspective of any of its major characters: the fussbucket designer, his ambitious and feisty new lover, or his imperious yet disarmingly tender sister and business partner. And like a Nabokov novel, it was both playful and not a little transgressive in its attempts to capture the sparks and vibrations that define our passions and obsessions. Alongside the works of those titans, we’ll be excavating new truths and mysteries out of it for decades to come. I’m not sure if Phantom Thread is Paul Thomas Anderson’s best film, but I’m certain it’s his most perfect one.

Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films, TV shows, and video games that kept us staring at screens. More from this series