Jean-Luc Godard is smart as hell. He's also punk as fuck. Two facts to keep in mind when approaching the works of this onetime enfant terrible of the French nouvelle vague. Because even after more than 40 years, the series of films Godard produced in the 1960s still have the uncanny ability to shock and perplex in equal measure. Anarchic, beautiful, occasionally impenetrable but always ridiculously cool, the movies that Godard wrote and directed during this decade changed the cinematic game forever. But where's the entertainment value? A frequent criticism I hear of Godard is that his movies are too weird, too fast, too jarring, his characters' motivations too opaque and “unrealistic” to become emotionally involved with. But that's just it. Jean-Luc Godard has no desire to entertain us. His films aren't meant to be entertaining; they're meant to be critiqued.

Susan Sontag, in an essay on director Robert Bresson (a favorite of Godard) had this to say about the nature of reflective art:

Some art aims directly at arousing the feelings; some art appeals to the feelings through the route of the intelligence. There is art that involves, that creates empathy. There is art that detaches, that provokes reflection. Great reflective art is not frigid (emphasis mine). It can exalt the spectator, it can present images that appall, it can make him weep. But its emotional power is mediated. The pull toward emotional involvement is counterbalanced by elements in the work that promote distance, disinterestedness, impartiality. Emotional involvement is always, to a greater or lesser degree, postponed. (Sontag, 1964)

The same can be said of Godard. At no time during the viewing of a Godard film is the audience unaware that it is watching a film. Jump-cuts, sudden silences, extra-textual cinematic references, fourth wall obliterations, vast blocks of Dada-esque onscreen text, sound and image track divergences, seemingly random voice-overs -- at times, Godard appears to be gleefully fucking with the basic building blocks of cinematic grammar, hacking the preconceived notions of his presumably film-savvy audience in order to throw them off balance, to disorient them just enough so that they are forced, at the very last, to depend upon the one thing in their possession they are rarely if ever asked to bring to bear upon the movie screen: their own native intelligence. Godard wants us to reflect upon what we are watching, while we are watching it. He wants an audience of critics, not passive observers/consumers. He trusts us to keep engaged.

Which makes perfect sense coming from a former critic. Godard and his cohorts at film journal Cahiers du Cinéma were among the first generation of cinephiles to have grown up within an already established filmic culture, a culture with its various genres, rules, and tropes firmly entrenched. And thus he was able to riff upon the entire history of film like a jazz musician, subverting our expectations, playfully commenting on the very nature and significance of the medium itself. In fact, Jean-Luc Godard never really stopped being a critic -- he simply changed mediums.

And yet, despite all the trickery, despite all the meta-fictional shenanigans, despite Godard's insistence that we as an audience shake off our habitual stupor and for once in our lives think about what we are watching, despite all this, his movies, at least during the 1960s, are just so very, very cool. There's a reason why Quentin Tarantino named his production company after one of Godard's films (1964's Bande à part a.k.a. Band of Outsiders) -- no one else has been able to capture the experience of being young and bored while living through late-period Capitalism (what comic artist David Lapham has dubbed “the innocence of nihilism”) quite like Godard. Think of the two hoods and their dame racing through the Louvre in the aforementioned Band of Outsiders. Or Jean-Paul Belmondo shooting out the sun in Breathless. No one else has ever made ennui and existential angst look so damn good.

Breathless (1959)

Breathless (1959)

Released in 1959 to near universal praise, Breathless made Godard an instant celebrity and Belmando a star. The story is simplicity itself -- after impulsively stealing a car and killing a highway patrolman, small-time hood Michel (Belmando) prowls the streets of Paris, trying to track down some moneys owed while simultaneously evading the cops and scheming to get into the pants of cute American journalist/co-ed Patricia (Jean Seberg). That's it. But upon this bare skeleton of a story, Godard has crafted a film of such raw, unbridled energy and vitality, such off-the-cuff romantic glee, that he somehow managed to blow a hole right through the history of cinema itself. As the copy on the back of the Criterion edition DVD of the film puts it: “There was before Breathless, and there was after Breathless.”

Make no mistake about it; Breathless changed everything. Filmed over a short period of time in and around the streets of Paris, Godard introduced a DIY aesthetic into the cinema by intentionally foregoing the traditional big film crew with its attendant lights and sound equipment (his nod to Italian Neorealism), instead opting for the more quick-and-dirty method of handheld cameras and semi-improvised, “spontaneous” dialogue (the script having actually been written concurrent with filming, the lines being called out by an off-screen Godard moments before the actors spoke them on film). No one knew where the story was going to go until the time came to film it. It could have been a disaster. But instead it's a classic, or should I say an anti-classic, a film that simultaneously gives the finger to cinematic tradition while mining it for all it's worth, acknowledging the past while simultaneously showing the way to the future. “This film that I took for the start of a new cinema I now see as the end of cinema,” Godard told an interviewer in 1964.

There is a weird sort of tension evident throughout the film. On the one hand, the techniques and settings employed by Godard and his crew reinforces the reality of the situation, grounding the film in the streets and cafés of quotidian Paris. Yet on the other hand, everyone in the film seems to know, at least subconsciously, that they are characters in a movie. This ain't Paris -- welcome to Godard-land. The credits give the game away from the start -- “Dedicated to Monogram Pictures” (early producers of low-budget Hollywood genre fare). Everything about Michel -- from his style of dress to his manner of speech to his casual misogyny -- is straight out of Hollywood Gangsterland 101. At one point, he is even seen standing in front of a theater on the Champs Élysée that's showing a Bogart flick (1956's The Harder They Fall), consciously aping his idol's cooler-than-thou gaze. And not just Michel -- everyone from his buddies in the criminal underworld to the pair of flat-footed detectives hard on his trail to the bystanders at the scene of a car accident seem to be in on the act. Reality in this film has been replaced by “hyperreality” -- the factual having been subsumed into the fictional. Everyone is playing a role. It helps that there are many cameos by filmmakers and critics, including a doozy by Jean-Pierre Melville, who portrays a sleazy writer being interviewed by Seberg.

Which brings us to the character of Patricia. What role is she playing? It seems to be that of an affectless little doll, a cute but dead-eyed cipher with impeccable fashion sense but little in the way of personality. It's almost as if she hadn't been clued into the whole “this is a movie” game at all. That is, until late in the film, when she finally cottons onto the fact that Michel is a murderer on the lam from the law. Then and only then does she seem to come alive, to gain a purpose, to finally know what she wants out of life. And yet, she remains an enigma. In fact, Patricia might be the key to this film, which can certainly and fruitfully be critiqued through the critical lens of Feminist Theory. (Marxist theorists, too, would have a field day parsing the relative socio-economic status of the two leads.)

After Breathless (or to give its French title, Á Bout de soufflé, which to my uncultured ear has always sounded like some kind of tasty French treat), Godard brought forth a series of increasingly challenging works, reacting perhaps to the implied pressures of having had such a huge hit on his hands the first time out. (If Breathless was Godard's Nevermind, then everything thereafter was a series of cinematic In Utero's.)

First up was Le Petit soldat, a cinéma vérité-style examination of the French-Algerian conflict. Although made in 1960, it was not released in France until '63 due to its incendiary political content. Mostly notable for the inclusion of Anna Karina, Godard's future wife and muse, it was followed by A Woman Is a Woman, Godard's version of a Hollywood musical. Also starring Karina (as well as Belmando), the Godardian musical is pretty much what one would expect -- a full-on postmodern deconstruction of the genre, filled with dazzling invention and verve, but almost no singing. (In other words, not at all what one would expect.) Not amongst Godard's major works, it was probably more fun to make than it is to watch.

In '62 came My Life To Live (Vivre sa vie), which according to Sontag is a “perfect” film and “one of the most extraordinary, beautiful and original works of art” she'd known. The next year brought Les Caribiniers, Godard's keenly funny anti-war satire, and Contempt (a.k.a Le Mépris), a film Colin MacCabe of Site and Sound once called "the greatest work of art produced in post-war Europe.”

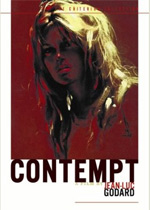

Contempt (1963)

Contempt (1963)

An exaggeration, sure, but not by much. Contempt is an extraordinary film, Godard's first attempt at big-budget filmmaking, and what would turn out to be his last. A work that deepens in significance with repeated viewings (as well as the amount of extra-filmic knowledge one brings to it), Contempt stars Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli as a married French couple living in Italy while Piccoli is contracted to work on a rewrite of a filmed version of The Odyssey being directed by an oracular Fritz Lang (playing the part of “himself”) and (mis)produced by crass American Jeremiah Prokosch (Jack Palance, who tears into his role with a particularly brilliant sort of smarmy gusto). The film chronicles the dissolution of their marriage over the course of a couple intense days in Rome and then Capri.

We begin outside the frame: a deep focus shot down a set of dolly tracks, camera crew at the far end tracking a woman as she walks up the lane toward us. The woman, we will soon find out, is Francesca Vanini, playing the role of Georgia Moll, assistant to Palance/Prokosch. The credits begin, but instead of the usual on-screen crawl, we hear the words being intoned to us by an off-screen presence. This immediately lends an intriguing level of added complexity, over and above the formal and thematic complexities to come. In a polyglot film such as this, much preoccupied with language and translation, it surely can't be seen as incidental that Godard chooses to present the credits to us in this manner. The film is obsessed with communication and its breakdowns -- with misunderstandings, mistranslations, and all the infinite things that can never be expressed with words. Language is paramount, so deciding on this more intimate method of spoken word surely has some significance.

As the camera and its crew grow larger on-screen, some of us may recognize the cameraman as none other than Raoul Coutard, frequent Godard collaborator and cinematographer of the very film we are currently watching! How is this possible? Where are we? Our ontological status seems to be in some doubt. The metaphysical paradoxes soon continue, however: “The cinema substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires.” As this quote (misattributed, perhaps intentionally, to Godard's friend and mentor, the late critic André Bazin) is spoken aloud to us by our invisible friend the narrator, Coutard looks to the sky and prepares to turn his camera. “Contempt is a story of that world.” And right then, right at the very moment of maximal self-referentiality, Coutard aims his camera directly at the audience. And the lens looks like nothing so much as an eye, like the glaring, all-seeing Eye of the Observer, the Destroying Eye of Shiva or Horus. And we are trapped then, pinned to our seats by its contemptuous celestial gaze.

Phew! All of that and we haven't even gotten to scene one! As we leave this liminal zone between fiction and reality and begin the story proper, we find ourselves in the bedroom of Paul and Camille Javal (Piccoli and Bardot). And there she is: Brigitte Bardot, superstar sex kitten extraordinaire, sprawled out naked for our critical appraisal. The room in suffused in red. As composer Georges Delerue's sumptuous score begins to swell in the mix, Camille asks Paul to critique her body, piece-by-piece. “See my feet in the mirror?” “Yes.” “Do you think they're pretty?” “Yes, very.” “Do you like my ankles? And my knees, too?” “Yes. Yes.” “See my behind in the mirror?” “Yes.” “Do you think I have a cute ass?” “Yes, really.” And so on. The room is suffused in blue. “And my face?” “Your face, too” “All of it? My mouth, my eyes, my nose, my ears?” She looks at him intensely. “Yes, everything.” “Then you love me totally.” “Yes. I love you totally, tenderly, tragically.” She looks down then, suddenly blue. “Me too, Paul.” And we know from the start they are doomed.

A wholly remarkable scene. And what makes it all the more remarkable is the fact that it was not originally included in the film! After Godard had presented his final cut to the studio without any nude shots of Bardot included, his producers were understandably outraged. How could they possibly release a film staring Brigitte Bardot, at the time the world's most famous sexpot, out into the marketplace and not include at least a little t & a? She was the main commercial draw after all, her face and name prominently displayed above the title on the poster. And thus was born this bewitching scene, which along with the previous credit sequence contains the entire film in miniature. All of the major themes are there, packed into the span of a few minutes. Godard takes what might have been a limitation and instead creates from it a holographic microcosm of the film's world, a doubling at least of its metaphorical power, reaching outside of the film's frame to embrace the world at large, the world outside the theater, where Bardot is an object of desire for millions. You want nudity? Sure, here you go buddy, here's your nudity: look at her. Pick her apart, audience. Pick her apart, Paul. It's no wonder she holds him (and us) in such contempt.

The entire film is like this – layer upon layer of meaning. In a film about a film about The Odyssey, everything takes on the depth and resonance of myth. (And I haven't even touched upon how beautifully shot it is, how rich it is with bold primary colors, amplifying the stark universality of its themes.) The centerpiece of the film is a tour-de-force, a long scene between Paul and Camille as they confront each other amidst the ruins of their bourgeois apartment. We watch then as Godard out-Bergmans Bergman, showing us in precise and excruciating detail how a marriage collapses. One could write an entire book on this scene alone. And then it's off to exotic Capri, where treachery and tragedy and the untamed beauty of the natural world awaits. And Fritz Lang calls action.

1964 and 1965 were both strong years for M. Godard. In '64 came (Bande à part and A Married Woman, while '65 saw the excellent Pierrot le fou and that outright classic of skewed science fiction, Alphaville.

Masculine, Feminine (1966)

Masculine, Feminine (1966)

In 1966, Godard gave to the world Masculine, Feminine, as perfect a pop confection as has ever been made. The film is about the feeling of being young and alive and horny and confused and bouncing around like a supersonic pinball in the bright and shiny world of surfaces we call modern life. No, not about -- it's not about these things, these feelings; it is these things, these feelings: Masculine, Feminine is pure uncut adolescent hormones in cinematic form. It's also quietly hilarious. (One of Godard's rarely praised talents being his keenly developed comedic sense.) Chaotic in effect but structured in form (it's neatly divided into 15 short acts, most of which have a title or number before it), the film's through-line is the tentative romantic courtship between philosophical poet-cum-revolutionary wannabe Paul (a wonderful Jean-Pierre Léaud, he of the The 400 Blows) and real-life up-and-coming yé-yé girl, Chantal Goya, playing the part of cute but vacant up-and-coming yé-yé girl, Madeleine.

Paul loves Madeleine, but Madeleine barely tolerates Paul. Robert wants to fuck Catherine, but Catherine is saving herself for Paul. And so it goes, round and round from café to dancehall to laundry to movie theater: “We went to the movies often. The screen would light up, and we'd feel a thrill. But Madeleine and I were usually disappointed. The images were dated and jumpy. Marilyn Monroe had aged badly. We felt sad. It wasn't the movie of our dreams. It wasn't that total film we carried inside ourselves. That film we would have liked to make, or, more secretly, the film we wanted to live.” But more than Norma Jean has been tarnished with age, and these kids, these “children of Marx and Coca-Cola” have been cursed to live in a world grown stale and flat, a world where everywhere they look they see adults acting inexplicably, where there's nothing left to do but desperately cling to the paper-thin surfaces of things: to pop and to fashion and to ill-considered socialist maxims, and if you can't get that girl to sleep with you, why then you can always try to cop a feel.

And of course any real connection is impossible, because how can you honestly express the things you feel in your heart? Sure, you can go into the little booth and pour your little words out onto little shiny vinyl discs, you can sit alone in the lonely café, writing down your lonely poems, but will Madeleine ever truly love you? Will she stop looking in the mirror long enough for that? Would she be sad if you died? Who knows. So. So what do you do? How do you connect with that pretty girl standing by the window? You interview her, that's how: you interrogate her, you take a poll. And so that's what Paul does in the film -- he becomes a pollster, checklisting the world around him through a series of questions on forms. And Godard, too, approaches his subject matter in the manner of a sociologist, studying it from all angles, capturing his footage on the fly, documenting how real people live in an unreal world. But in the end, Paul comes to realize the inherent bankruptcy of the pollsters' stance. He has become, at last, a true philosopher: “Wisdom would be to see life, to truly see it. That would be wisdom.” And to see the beauty behind the surface, to be able see the beauty inherent in the surface, that is what Godard has done here, and that is what he has helped us to do as well with Masculine, Feminine.

Jean-Luc Godard directed seven more full-length films before the decade would run out, including one political tract in cinematic form (La Chinoise – too didactic for my tastes), one schizophrenic documentary about The Rolling Stones (Sympathy For the Devil) and at least one all-out classic (1967's apocalyptic satire, Week-End). But the last film I'd like to focus on is one of my favorites, a dense and challenging little oddity, also from 1967 -- Two Or Three Things I Know About Her.

Two Or Three Things I Know About Her (1967)

Two Or Three Things I Know About Her (1967)

Part essay, part philosophical treatise, part social and political satire, part exercise in civic planning (seriously), Two Or Three Things I Know About Her might well be Godard's most personal film of this period. Forget his fractious marriage with Karina and how those tensions may or may not have factored into his work. For my money, it is here in this incredibly complex and almost theoretical film that Godard finally lets his guard down and allows himself to stand fully revealed to us at last. Revealed as what? As an intellectual. Sontag again: “Godard's films are about ideas, in the best, purest, most sophisticated sense in which a work of art can be ‘about' ideas.” And so ironically, it is in this most alienating of films -- a film that intentionally keeps its audience at (more than) arm's length; a film in which zero concessions are made to the usual concerns of plot, character, or coherent structure; a film, in other words, that almost dares you to like it -- that we can feel Godard's presence most clearly. He is right there with us in the dark of the theater, urgently whispering something in our ear we simply must know.

If Godard was playing the part of the sociologist in Masculine, Feminine, here he is instead a biologist, studying the organically interconnected nature of all existence, centered perhaps upon the city of Paris (the “her” referred to in the title) and personified equally by the actress Marina Vlady and the character she (most self-consciously) portrays, Juliette Jeanson. Everything in the film is amplified and reflected by everything else in the film, on all levels: from the ever-present noise of jackhammers and backhoes in the Parisian streets to the war in Vietnam, from the way that the characters casually and continuously break the fourth wall to the fact that it is Godard himself who whispers the intermittent off-screen monologues, from the swirling of the foam in a cup of coffee to the shots of framed pictures of flowers, arranged separate and alone in a field of grass -- everything has its place, everything is of a single and unified piece. So of course this makes the job of the critic all the more difficult, since to pick apart the threads that make up Two Or Three Things I Know About Her is to rob it of its singular nature. But onward. I'd like to focus in on two aspects of the film that I find particularly intriguing: the nature and limitations of language and the theme of prostitution.

We never find out why Juliette has become a part-time prostitute, although it seems to be out of simple boredom. In any case, it's apparently the thing to do -- we see several practitioners of the world's oldest trade in this film, many of them married mothers. (In at least one case, the woman's husband is also her pimp.) Liaisons are held in cheap hotels and at one point in a rented office space decorated with travel posters whose proprietor accepts consumer goods as payment for both the use of the rooms and for the makeshift daycare he provides to children of women while they transact their business. (Reading over that sentence, I am reminded once more of the absolute folly involved in trying to coherently explain this movie -- suffice it to say that the scene in question makes perfect sense in context, and that it is both funny and shocking in equal measure.) Most likely, Juliette and the other housewives have turned to whoring in order to have more money so they can buy more, consume more, acquire more. And in so doing, they have become objects, both literally and figuratively. Juliette is that classic Godardian woman, a type we've encountered again and again in this survey: beautiful but blank, empty both inside and out, always looking over the horizon for what comes next. In other words, she is us. Or at least how Godard see us -- all of us prostitutes, all of us empty, all of us unsatisfied with our lot in life. And he most definitely does not exclude himself from this damnation.

At the center of the film is a scene of transcendent aesthetic achievement that ranks amongst the best in all of Godard and hence in all of film. It takes place in a café, where Juliette has come in late afternoon to rest a bit before continuing on with her day. The centerpiece of the scene is a stunning closeup, an overhead shot of a cup of coffee being stirred, foam and bubbles swirling in poetic fractal patterns while Godard delivers a dazzling and wide-ranging musing about language, about how it both isolates and unites us as objects existing in society, each object the outward manifestation of a secret inner subject. Godard excoriates himself for failing to adequately communicate his ideas to those around him; he is crushed by the isolation of subjectivity: “God created heaven and earth. But one should be able to put it better to say that the limits of language, of my language, are those of the world, of my world... and that in speaking, I limit the world, I end it.” We are reminded of a scene in the beginning of the film where Juliette's son asks, “What is language, Mommy”? “Language is the house man lives in,” is her enigmatic answer.

Juliette leaves the café. As she crosses the street, she casually recounts for us a spiritual awakening she had earlier in the day (which Godard had pointedly not shown us at the time): “I don't know where or when, just that it happened. I have tried all day to recapture the feeling. There was the scent of trees. I was the world... the world was me.” She had reached the limits of her language, and for a brief moment she was one with the Universe. And then, Juliette, as God, spoke the words that created heaven and earth.

Jean-Luc Godard is the subject of a five-week retrospective at New York City's Film Forum, which started in early May.