When a new compositional technology becomes available, a seemingly endless amount of ideas arise on how best to employ it. But it was the advent of electronic recording capabilities that revolutionized the way almost every modern musician operates, not just by shifting the primary document from the score to the recording, but also in creating new ways to edit, manipulate, and ultimately compose sound without any “real instrument” in hand. Sound becomes data.

The Getty Address, Dirty Projectors' 2005 album released on Western Vinyl, is a breathtaking arrangement of "sound data" chiefly manipulated on the computer instead of played on a fret board. In recent years, Dirty Projectors have developed a sound and rapport with fans and critics, particularly with this year's Bitte Orca and the harmonically and conceptually masterful Rise Above from 2007. The Getty Address, however, is often overlooked as a compositional gem in itself. The album was intended by DP songwriter David Longstreth as a “glitch opera,” created from pre-recorded sounds from over 25 musicians, strung together without a specific end goal in mind. The opera's libretto is a dense amalgam of phonemes and obscure epithets, and although the album tackles a lot, the way the composition meditates on the process of writing modern music is perhaps its most enduring attribute.

One reason for the album's genius can be found in its deconstruction of modern recording techniques. Unlike an industry obsessed with studio trickery -- fades, compression, Auto-Tune -- to hide the computer editing process involved with digital recording/mixing equipment, Longstreth purposefully emphasizes the computer-based processes of editing and composing. The “glitch” descriptor is indeed derived from this concept; not only do the cuts and stutters of the tracks remind the listener of their electronic origins, but they also become a texture unto themselves, imbuing the piece with a beautiful transparency of process.

Out of The Getty Address' 13 pieces, “Jolly Jolly Jolly Ego” stands out because of its aurally separable drum tracks, radically cut-up vocal melodies, and metrical manipulation. The recording undulates between obvious and formidably complex ways of exposing the compositional pieces that create the whole. By exposing how the piece was assembled, the previously unchallenged agency of the composer is simultaneously humbled in the process.

This article is an in-depth analysis of this piece. Straying from the cultural analysis that typically comprises this site's approach to music writing (and recent musicology), I'll examine each section of the song and demonstrate how the rhythms, lyrics, melodies, and production construct a whole that invites deconstruction by reflecting upon the elements of its creation. The term glitch will be used to denote any concentrated, computer-generated disruption of harmonic or rhythmic fluidity -- for example, egregiously dropping a beat or rapidly cutting up a melodic line. Further, each glitch will be described in terms of its function as well.

As the analysis mostly describes the song in order of section, the article is best used as a companion to the recording.

----

----

- SECTION A

The piece's introduction (Section A) begins with a rather disorienting drum construction that takes a few cycles to be properly felt. The groove is constructed by four different instruments -- hi-hat, triangle, xylophone, and drums -- divided up clearly by their positions on the stereoscopic spectrum. Whereas other compositions use delay in order to discretely thicken the texture, Longstreth hard-pans each hi-hat track, exposing the delay effect used in their making. It seems most likely that the original hi-hat track was delayed by a sixteenth note to create the composite ping-pong effect or back and forth motion (Figure 1). This bouncy rhythm also adds credence to the piece's title.

----

This effect is illuminating on its own, but it's even more egregious contrasted against both the steady triangle hit on the downbeat and alternating bass-snare hits on beats one and three, respectively. The back-and-forth motion of bass and snare coupled with the familiar tinkle of the triangle both acts and sounds like a metronome for the complex hi-hat pattern. This metronome illusion is a musical way of keeping time, simulating the “click” tracks found in music-editing software. Cut-up vocal and xylophone lines with no fades to smooth the incisions remind us of Longstreth's editorial presence. Within eight seconds, the piece has already divulged its own compositional language.

After the introduction, Section A introduces a recurrent theme, the choir's rhythmically displaced vocal lines (Figure 2). Repeated three times, the clarity and simplicity of the line sets up a contrast for the convoluted stutter at the end of each iteration. The glitch in measure 14 of Figure 2 acts as a reset for the rhythmic displacement, interrupting the eccentric 3,3,6,7 beat pattern for each note in the line. If this 19-beat sequence were to continue without interruption, it would be hard to find a resolution for the phrase. The computer-editing is transparent, playfully rhythmic, and, in this case, acts as a resolution for a rhythmically irrational line.

----

----

----

- SECTION B

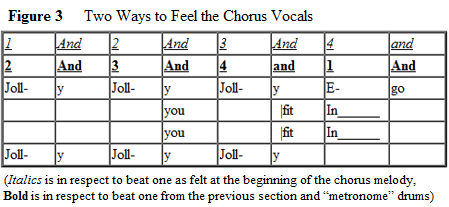

Section B, the chorus, is preceded by an extended glitch transition, twice as long metrically than the usual end to the vocal phase in Section A. The melody starts on what sounds like beat two of the measure, but because it is glitched, Longstreth treats it as a malleable beginning to the sixteen-beat phrase chorus cycle. The main melody can be coupled in fours, and although the lyrics might seem meaningless, they contain interesting clues about the piece. Figure 3 is a metrical deconstruction of the rhythm as felt with and without the choir-glitch shifting the feel of beat one. In the first line of the chorus melody, “jolly” is repeated straightforwardly three times, ending with an “ego” that seems to confirm the original placement of beat one. The next two “you fit in”s, however, slide aptly between the downbeats, making ambiguous how Longstreth wants listeners to feel the beat. Three more “jolly”s remind the listener of the beginning phrase, but contain no resolving “ego.” The lack of a final “ego” in the chorus is symbolic, as the lack of resolution continues the sense of an unclear beat one. With no decisive end or beginning, the section is clearly controlled by a computer that doesn't require a clear beat one, let alone a breath of air.

----

The timbre of the chorus vocals (and the other sung lyrics) is intriguing because of its layering technique. Aware of the popular tactic of multi-tracking unison vocals to create a “shimmer” effect, Longstreth does something similar, but hard-pans the tracks left and right to deconstruct the effect. A slight delay added in the right channel echoes the delayed hi-hat effect and again shows the method of construction. Further, the offset vocal tracks occasionally results in harmony, as the delay coupled with Longstreth's rapid vibrato makes the two melodies of quicker passages come close to layering on top of each other. While this is a rare form illusion in such a lucid piece, it's an anomalous harmonic tactic that calls attention to the traditional fabrications of multi-tracked harmonies. Unlike with a group of backup singers, this sort of harmony is only feasible with a computer-generated delay.

----

----

- SECTION C

After the chorus is completed, the piece segues into the first verse (Section C). The lyrics in this section also tie into the piece's construction. The cut-up, cascading vocal line found in the introduction at 0:14 duly returns at 2:11, directly after the line “let the water bead off your naked shoulders.” “Naked shoulders” is an image of simplicity and bareness, two characteristics of the piece as a whole. Longstreth's vocals, often compared stylistically to out-of-place R&B, riff off the sensuality of naked shoulders as a metaphor for the beauty of naked electronic compositions. “Bead” also sounds like “beat,” suggesting a musical stripping away of concealed artifice. “Bead,” in terms of water, connotes a dripping action, which ties into the piece's contour as a whole. The piece's beginning is the densest and the coda the most minimal, with each section losing an element after or during the pivotal glitch.

----

----

- SECTION D

At 2:22, Section D, an unprecedented saxophone enters and sets in motion a chain of deconstructive musical events that are the most memorable and dramatic glitches. The “metronome” (bass and triangle) sound is confused as the triangle doubles up on itself at 2:23 before cutting out completely. The descending vocal melody from 0:14 and 2:11 is played again, but accordingly with the backbeat, it's lacerated beyond recognition. This glitch is stark not only because the line has been played several times already, but also because the vocals are heard unadulterated at 2:18, right before the saxophone enters on Section D. At 2:33, before the section change, an errant drum hit can be heard softly in the background, a reminder that the piece was constructed from previous material, not “perfect” studio takes. The decision not to exclude what almost certainly was an accident at such a pivotal juncture in the piece's structure shows just how stringently Longstreth stuck to his no-frills formula.

----

----

- SECTION A''

The saxophone disappears, never to be heard again, as soon as A'' arrives with a recapitulation of the choir melody. This time, however, with the metronome gone and the substantial disruption preceding it, there is an entire system glitch after only one iteration of the wistful choir line. At 2:45, beat four is dropped as it becomes beat one, a subtle but poignant reminder that even the perpetual snare and bass can be altered at the click of a mouse. This dropping of an entire beat could also be construed as a counterpoint to the ambiguity of beat one in Section B (the chorus). Since the chorus started on what seemed like beat two, perhaps this is Longstreth's subtle way of resetting metrical justice. Fittingly, a quick reminder of the chorus takes place on beat two at 3:00, except this time, the lyrics “you fit in” occur on beat one, not the "and" of two, a symbol of closure before a quite different second verse. After a few more chorus cuts are made at 3:05 to wipe the slate for the new section, an ascending orchestral line paves the way for the second verse at 3:23 while also divulging the melodic material to be used in the coda. This setup (and later deconstruction) mirrors the use and discarding of the descending vocal line at 0:14 and 2:11.

----

----

- SECTION E

Longstreth's second verse at Section E creates one of the strangest lyrical mysteries of the entire album. Pulled across bar lines but filled with smooth alliteration and assonance, Longstreth croons: “Clung to obstinate/ Like an old love/ Letter/ Boxed in her back pocket/ Lacking lust/ Or living saliva/ Dried blood/ Like a wax seal scabbing/ Regal.” A look at Figure 4 shows the natural delivery of Longstreth's unusual lyrics. There is no regularity, although the melodic contour does roughly correlate with the accompanying strings. Still, the natural rhythms are almost impossible to accurately transcribe, raising the possibility that Longstreth recorded this and his other vocals with only a rough idea of the harmony and backing rhythm in mind.

Apart from providing one last contrast between the remarkably smooth verse and the choppy finale, these lyrics and their subsequent delivery also offer one last open portrait of the subject matter. With no clear place or topic, the verse thrives on the multiplicity of interpretations. Longstreth's odd line breaks, such as “Like an old love/ Letter,” make the lines comprehensible in more than one way. The gliding, free-form contour of the melody reflects the same unfettered aesthetic. Indeed, the sounds and smoothness of the words contrast effectively with the sharply edited coda.

A brief final preparation begins at 4:02, where the texture is thinned by the removal of string lines but sprinkled with a reprise of the final couplet from the last verse. The xylophone also makes its last appearance in this pre-coda, an easy exit to overlook. Longstreth's decision to use the chopped-up xylophone as the equivalent of a rhythm guitar throughout the piece makes sense because of both its similarity in timbre to the triangle and its opposition to the way the sample is cut. The xylophone creates a very “pure” (sinusoidal) frequency, but also has a very short decay. Consequently, Longstreth was able to sharply cut the xylophone source material with a minimally jarring effect.

----

----

- SECTION F

At 4:38, Section F (the coda) begins with the same ascending line that started the second verse. This finale is counterintuitive but appropriately the thinnest texturally; by stripping away even the exposed drum tracks and xylophone hits, Longstreth's hand is even more present. Each string line ascends increasingly higher, with the final part of each cut up fiercely. A subtle but disorienting and rapid stereo pan occurs at 5:00, echoing the tactics of the long-gone hi-hat and vocal tracks. The piece ends with an ironically beautiful layering of reversed and regular strings. Although this final gesture seems out of place in such a jagged piece, the inclusion segues into the album's next piece, “Time Birthed Spilled Blood.” This composition is one of the most rhythmically straightforward and texturally dense tracks, so Longstreth's desire to tie up “Jolly Jolly Jolly Ego” in a more traditional fashion fits the aesthetic transition.

Although the components of “Jolly Jolly Jolly Ego” are shown lucidly overall, Longstreth did, of course, make compositional decisions in what recorded material to use and how to sing over the fragments. Even though the piece begins with a language much more transparent than most electronic compositions, it deconstructs its own methodology through each “glitch.” Perhaps representing the computer's power to give and take, each glitch gives way to new sections while knocking off the (relatively) traditional elements of rhythm and harmony.

By challenging the listener to focus on these glitches and other components of the piece's compositional process, Longstreth actually helps the music analyst work, artistically agreeing with critics like David Lewin who believe that “theory or analysis [are not] ‘ultimately' irrelevant to composition.'” Longstreth certainly did an analysis of methods in other electronic music before putting his piece together: the ability to critically process and react to popular and established styles is at the center of the song's thrust.

Whatever role the glitches may play in one's individual interpretation or experience of the piece, there's no doubt that Longstreth's decision to strip away the usual makeup is a fresh approach to using the studio as an instrument. It is certainly true that several of Longstreth's techniques are not his own or have been interpolated into the accepted vernacular of computer music -- such as DJ scratching -- to expose the medium at hand. However, The Getty Address' process of cohesively assembling transparencies as a fluid and musical tool reflects the prescience and musical reflexivity that few composers are lucky enough to have.