Last week, your mom got an email at work labeled “Die Antwoord – ‘Zef Rap!’ Look at This!” It was sent to the entire office by Betty, a permed and confirmed bachelorette from Accounting who followed it up about a half hour later with “Dog and Parrot are Best Friends! Wow!” In the weeks since Boing Boing woke up (on February 3rd, 2010, to be exact) and decided to briefly replace its usual Google-related infographics with cutting-edge musical tastemaking, Die Antwoord’s various videos and music streams have been proliferating around the net like zero-marginal-unit-cost crack cocaine. Now they’ve signed with Interscope, and while signing to a major label nowadays is a dicey proposition at best, it’s still a symbolically powerful capper for one of the most fantastical ascents ever from musical obscurity to something resembling fame.

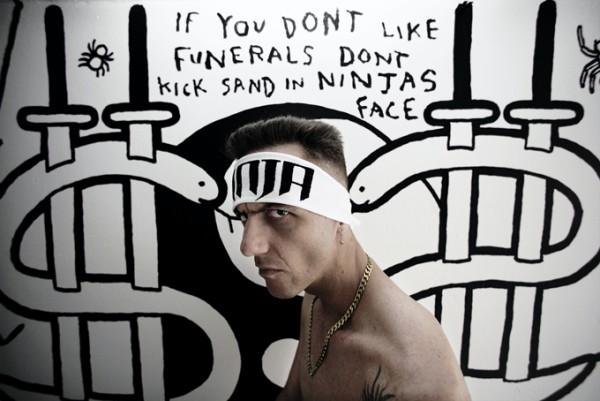

Die Antwoord (Afrikaans for “The Answer”) are making great music and borderline genius videos, all while giving impeccable is-he-or-isn’t-he-taking-the-piss interview. DJ Hi-Tek (and how much does it up the ante of otherworldliness that these guys gave their producer the exact same name as a famous American beatmaker?) delivers to a stylish sweet spot with his super-clean drum-machine beats and grimy synths, but the songs take the underlying irony of 80s throwback fashion and make it more than it deserves to be — creative, compelling, moving. Yo-Landi Vi$$er’s space-oddity, Björk-topping singing voice and sharp, dynamic, foul-mouthed raps are the Colonel’s secret blend for hipster crushes, while leader Ninja (a.k.a. Watkin Tudor-Jones — seriously) offers the unwinking hyperbole and lyrical excess to sell you Afrikaans slang as the new perfect language for working out your angst (You fackin’ poes). Their debut album isn’t “out” yet (whatever that means), but you can stream the whole thing at their website. It goes effortlessly from the semi-kitschy self-referentiality of “Enter the Ninja” to the it-could-be-The Knife subtle pulse of “$O$,” hinging on “Beat Boy,” which starts as a goofy Eurotrash sex-fantasy and morphs, almost despite itself, into something really transporting.

Without all that real-life excellence, their ascent would have stopped much shorter. But what took Die Antwoord over the top into ‘phenomenon’ territory is that they’ve got a story, the kind of convoluted and self-contradictory origin that launches a million debates into the online maelstrom. There are layers and layers, but the heart of the matter is that Die Antwoord are Afrikaners — one of two white ethnic groups that helped establish and maintain the Apartheid system in South Africa until a mere 17-odd years ago — and they’re aggressively copping the visual and auditory style, from tattoos to accents, of Cape Town’s Black and Coloured (mixed-race) gangsters in the Cape Flats (a.k.a. “Apartheid’s Dumping Ground”).

Die Antwoord are a uniquely powerful and, for many, exotic version of the musical miscegenation that has driven most 20th-century pop. And like Americans from Elvis to Eminem, Die Antwoord make us ask whether the children of exploitation — Americans, Australians, Brits, French, Japanese, and Germans — can respectfully adapt the culture of the formerly exploited, or whether that’s just the same exploitation continued in another form. Commentators from around the world have tried to tell everyone how great Die Antwoord are while simultaneously, and with varying levels of competence, scrabbling up the side of a mountain of strange history and politics in the hopes of discovering whether it’s actually okay to like them. Words like “authenticity” and “cultural legitimacy” are cropping up from New York magazine to The Guardian, leaving me desperate to blast “Wat Pomp” just one more time before it is fully transformed from aggro jam to political object lesson.

Die Antwoord are undeniably fake, and not just in a neutral, theatrical way that we can or should shrug off as par for the course in the postmodern funhouse. They’re fake in a way that shows up the lies that we tell about ourselves, reminding us that at some level it’s all theater and makeup, no matter what color we are.

A lot of commentators, particularly Americans, have been comfortable staring into this funhouse mirror and shrugging nonchalantly at what it reflects. Many have claimed that, since authenticity is a dated concept anyway, nobody has any reason to get worked up about any ‘controversy’ surrounding Die Antwoord. As Sasha Frere-Jones sanguinely put it, the band’s politics can “be refereed by South Africans; everyone else can unravel the band’s musical preference…” MTV blandly assert that since “Beyonce’s as fake as Alice Cooper,” implying that Die Antwoord’s fabrications are equally inconsequential. Some South African referees come up with similar scores, for instance the very thorough and thoughtful writers at Mahala, who allow that “the appeal of Ninja and Yo-Landi is in this danger, in the knife-edge between cheese and brilliance, between horror and humor, between make-believe and reality and the refusal to explain.” Similarly generous is the high-minded take offered by one Annie Klopper, who interprets Die Antwoord as a version of Mikhail Bakhtin’s ‘carnivalesque,’ a satirical overturning of all social norms. In short, the fashionable line is that throwing somebody else’s culture into a fuck-it-all blender and making it your own is either a morally neutral tactic for musical bliss or an active subversion of corrupt and overstaid social norms. It seems appropriate, then, that one of Die Antwoord’s earliest interviews was published by Vice, which has turned the refusal to pay respect to race, gender, psychological impairment, or any other matter of cultural sensitivity into a lucrative business model. As Yo-Landi flatly intones on the album’s opening track, “Whatever, man.”

The group is on the same page with their commentators’ flippancy. Just check their homepage for the alluring terribleness of the group’s fashion sense and the photographic aesthetic that documents it — box fades, femmullets, prison tats, and gold teeth all lit with the calculated crappiness functionally trademarked by Terry Richardson (the respected photographer Roger Ballen took mysterious black and whites of Die Antwoord, quite different from the grimy ones adorning dieantwoord.com). At first glance, the idea driving Richardson and the entire subsequent School of The Shit-Tacular is that overeducated whites need to be reminded of the joy of not giving a damn, acting without thinking, crushing beer cans against their skulls and laughing about the scars. A whole swath of marginally campy, ironic-but-not-really appropriationists have assumed a similarly gleeful carte blanche in taking whatever they want, as long as it sounds good. In here, you’ve got your Major Lazer, your Girl Talk, your MSTRKRFT, your Rat-Tat-Tat (we hardly knew ye), acts whose love of funk and hip-hop twists it into forms so exaggerated you can’t take them seriously or deny their power. It’s the musical equivalent of Inglourious Basterds, or maybe Lenny from Of Mice and Men, acts that love their source material so hard they kill it and must reanimate it in new form.

We’re talking here about mostly white tributes to nominally black art. That divide stands in for a hundred others around the globe, either subcategories of it (Afrikans and Xhosa) or multicolored parallels (Japanese and Koreans; Greeks and Turks; Israelis and Palestinians). But does semi-campy culture-clash music really offer anything to 21st-century efforts to move past the genocidal hatreds of the 20th? There are a few dissenters to the Die Antwoord love-fest, and though these are mostly backlashers, cranks, and morons, there is a legitimate point beneath the varieties of reactionary whinging. The most powerful, thoughtful objection so far comes from Mungo Adonis at Mahala, who actually took Die Antwoord’s music around the Cape Flats and played it for the Coloured people she’d grown up with. The verdict is that a lot of people in the Flats have never heard of Die Antwoord, Ninja’s accent is obviously fake, and even hardcore gangsters think their beats are fire. Adonis describes the appropriation as “high-concept and insincere,” which pretty much sums up the hipster-black culture connection. What are the chances Rat-Tat-Tat would be anything but profoundly uneasy actually hanging out with Bun B?

Of course, if you think about it just a bit, it’s weird to claim that the people of the Cape Flats get some kind of definitive up or down vote on Die Antwoord. Lawrence Lessig and the Free Culture people have convinced us that legal copyright is a bad idea — strictly controlling ideas as if property kills creativity. By the same token, if we gave people some sort of cultural copyright on the music/art/literature that came out of ‘their’ culture, nothing new would ever happen. Without New Yorkers into Kraftwerk, hip-hop itself would have been, at best, a profoundly different music, and if you really take it back, the blues is indebted to English folk song. And so on. The dimension of sincerity/insincerity is a further criteria of judging these infinite thefts, but it’s certainly imperfect. Think of Sacha Baron-Cohen or Sarah Silverman’s powerfully revealing comedic lies, or by contrast, the absolute wretchedness of a lot of very sincere “World Music” made by guys who advertise their 1/48th Cherokee blood. Sometimes fake can be just as good, or even better, because it’s a way of acknowledging that there really are differences between people. It’s certainly more legitimate for Die Antwoord to be semi-campy and subtly goofy than to try and play it entirely straight.

Ninja gets just to the right and wrong of it on the first track of $O$, when he claims to represent all of South Africa’s ethnic groups “all fucked into one person.” It’s an acutely discomforting claim — Ninja is 35 if he’s a day, which means that he spent at least some time as a beneficiary of Apartheid, so him claiming to represent the suffering of its victims is bullshit on the face of it. When Ninja refers to himself as a “wild fuckin’ savage,” we have a right — in fact, an obligation — to be uncomfortable with the echoes of how whites have used and abused the image of nonwhites over the past two centuries. But that discomfort is part of the point, with Ninja’s grandiose claims on the same level of provocative hyperbole as when he opines, mid-bridge, that “this is the coolest song I ever heard.” Those decrying Die Antwoord as exploiters seem to totally miss the rampant smirk. You can’t blame the artist for an audience (or bloggers) that are thick as a brick.

Sometimes fake can be just as good, or even better, because it’s a way of acknowledging that there really are differences between people.

Even when such egregious missteps are not carefully considered, they’re part and parcel with the obvious, real love that comes through in the intensity of the music itself, and without that we’d have nothing — no thesis, no antithesis, no controversy, and no conversation. What more could you want for the future of South Africa than an Afrikaner who actually wanted to be Coloured as badly as Ninja (the character — Waddy the man is a less clear story)? Die Antwoord’s tinge of comedy makes that love slightly distant, but that’s exactly the space where we can slip in some reflection. Just compare Ninja’s ambiguous irony and Fred Durst’s limitless sincerity, and ask yourself which is healthier. Irony helps Die Antwoord draw a clear but permeable line between participation and belonging, making their music an awkward but compelling (and in the end, powerfully sincere) answer to the most important question of our time: How Do We Get Rid of These Ghosts?

People still get pissed off about Graceland being exploitative of mbaqanga musicians, and we can’t deny the unjustly tempered careers and literal corpses of too many ripped-off musicians to mention. Part of Die Antwoord’s responsibility as fake-ass thugs is to provide us a good guide to their inspirations, especially since much of their audience promises to be outside of South Africa. But there’s a different kind of exploitation, inherent in every moment of cultural crossover, beyond the money at stake — not theft, but transformation, which is really hard to distinguish from misuse, distortion, misrepresentation. As Mungo Adonis found, the result might not be recognizable, much less enjoyable, to the people the original was stolen from. To get to Ninja claiming that he’s the entirety of South Africa, no doubt someone’s culture has to get fucked — and anytime there’s fucking, odds are about even it’ll end with resentment and regret.

But saying that we should ‘respect’ the cultures of people different from us is like saying that men should ‘respect’ women — a stance easily slipping into cold distance, layered with resentment and not a little fear, and punctuated with cautious, insincere connections that feel like nothing at all. “Respect” is B.B. King at the House of Blues. “Respect” is Wynton Marsalis running Jazz at Lincoln Center like a mausoleum. Die Antwoord are like that guy wolf-whistling out the window of his Trans-Am — he may not be subtle, but you know he means it. Again and again, music history (much like women) rewards the asshole with passion. The Beastie Boys were clowns 20 years ago, fearlessly answering back a culture they had no real claim to, while MC Serch did a dutiful apprenticeship on Brooklyn stoops. Who was being respectful? And who matters most today?

Saying that an artist has a claim to his work — for instance, that Jimmy Page should buy Muddy Waters a solid gold car — is totally different from extending that claim to their sisters, children, neighbors, political allies, or just people who kind of look like them. Even the word “culture” is risky, if it makes us think an album is created by a thousand people instead of by four, a sound by the entire Cape Flats instead of by twenty, or a ‘lifestyle’ by South Africa instead of five hundred hardcore drug dealers. Die Antwoord are undeniably fake, and not just in a neutral, theatrical way that we can or should shrug off as par for the course in the postmodern funhouse. They’re fake in a way that shows up the lies that we tell about ourselves, reminding us that at some level it’s all theater and makeup, no matter what color we are. While the people of the Cape Flats are right to think Ninja is pretty far from representing them, we might wonder whether their love of Tupac is any more well-placed.

Die Antwoord’s claim to “represent South Africa” is comedic and delusional and deadly serious, their smirk the only way they can be sincere. What’s at stake is clear when $O$ repeatedly calls out Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s current President, a Zulu who has faced charges of corruption and rape and, apparently, interfered politically in the former trial. Wrapped in absurd skits and winking raps, the shots at Zuma cut deep and ring true, simultaneously faux-moronic and palpably enraged at injustice and abuse. In the US, we have our own cadre of whites lambasting a black president, assorted Truthers and Teabaggers with zero sense of humor whose documents and theories mostly just prove that they’re paranoid-delusional racists. Most Teabaggers would nod their support for Respect and Diversity (especially if there were a camera around), ideals that leave us all at a safe distance from one another. Willingness to engage, to reflect, to steal and recycle (even with a wink and a nod) gives us ever broader common ground (even if we use it to tell each other to piss off).

We’re certainly not in a post-racial world, but the fear of stepping on somebody’s cultural toes seems to be in ever-stiffer competition with hatred and ignorance for Leading Perpetuator of Keeping it Separated. It’s up to disrespectful mindfuckers like Die Antwoord to plant the demon seed of confusion in all of us, no matter how cultural conservationists and xenophobes might object. I’d speculate that SA’s far Right are more than happy to “respect” the Cape Flats, and any other settlement still recovering from the ravages of Apartheid, by not going within a hundred miles of them. Die Antwoord, meanwhile, are running full-tilt at the barriers of history, not worried about whether they’ll end up ass over teakettle — after all, that’s part of the show.

David Morris can be followed on Twitter at davidzmorris.