Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films, TV shows, and video games that kept us staring at screens. More from this series

The common perception is that we are in the midst of another golden age of television, that — given the rise of auteur-driven prestige dramas and the breadth of styles, topics, tones, and senses of humor — there’s now something out there for everyone. What has changed, however, is not a massive shift away from mind-numbing reality shows, soulless network comedies, and countless CSI/NCIS spinoffs and toward the sorts of thoughtful highbrow and offbeat lowbrow shows that dominate our list, but a drastic alteration in the ways we access television. The old model of broadcast television suggests in its very wording that it was transmitted to us rather than either chosen by or curated for us — for better or worse, people were forced to consume what was served to them.

The proliferation of subscription-model television — driven by Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon, as well as the once-pricey premium channels, HBO and Showtime — has now made hundreds of TV shows available even to the many brave enough to cut the cord. This has given executives, showrunners, and artists alike the bravery, and certainly the profit motive, to actually refine their shows for something other than the lowest common denominator, allowing them to reach niche audiences craving something a bit too audacious, strange, or challenging for traditional networks. It’s impossible to imagine more than a few choices for our favorite TV shows of 2016 airing even a pilot a decade ago, let alone receiving the critical love and ratings necessary to justify their continued existence.

Coupled with the exponentially expanding ways in which we access and watch TV is Hollywood’s growing disinterest in the mid-level budget material that its 70s Renaissance brought to the fore before the age of the blockbuster gobbled up every last dollar once reserved for their production. Aside from a handful of established auteurs (and our Paul Thomas Andersons, Coen Brothers, and James Grays are slowly fading from the multiplexes), the $10-50 million budgeted films are simply not greenlit like they used to be. And as American cinema forks toward the low-budget indies on one side and Hollywood blockbusters and prestige pics on the other, in steps television to fill in the gap. Whether it’s the Fincheresque Mr. Robot and The Night Of or the Soderbergh spinoff The Girlfriend Experience, it’s clear that a number of TV shows have reached a level of personalized aesthetic and thematic expression that was once solely relegated to cinema.

In this new televisual landscape, we found a plethora of shows that pushed the boundaries of what the medium can accomplish. From Louis C.K.’s intimate, personally financed Horace & Pete and Donald Glover’s hilarious and confrontational Atlanta to socially and philosophically challenging epic documentaries like OJ: Made in America and HyperNormalisation, the sheer array of wit, intelligence, and formal experimentation that television offered us remains a bright spot in a year that most of us will not remember fondly.

Along with a few mainstays from last year’s list, we also discovered new delights in the absurd (Baskets, Lady Dynamite), reminding us that TV can simultaneously be hilarious and emotionally complex, that mindbending sci-fi (Westworld, Black Mirror, Stranger Things) can, with equal aplomb, delve into our deepest anxieties and desires or whet our appetite for nostalgia. But if we learned anything through our experiences with TV this year, it’s that television is rapidly evolving into something unrecognizable from what it once was. It continues to break free from the shackles of network executives and the implacable demands of advertisers. Thankfully for us, it has become all the better because of it.

20

Million Dollar Extreme Presents: World Peace

Created by: Million Dollar Extreme

[Adult Swim]

To understand Million Dollar Extreme: World Peace, imagine a Portlandia that doesn’t try to make jokes or skewer such an easily-circumscribed (sub)cultural target as liberal hipsters. Or, Portlandia voted for Donald Trump, but maybe as performance art. Sam Hyde, Charls Carroll, and Nick Rochefort’s sketch comedy show features the Flint water crisis as mixology, breakups, a pickup artist giving a disabled dude tips to get pussy, blackface, and weightlifting: all the hot takes in your FB timeline — or Reddit feed, if you nasty — melted. It is really dumb, but in a way that seems difficult to achieve. How can something so meaningless and empty have such an innovative sense of self? Adult Swim cancelled MDE: WP after one season because Sam Hyde posts stuff about liking Donald Trump on his Twitter, and some writer for Buzzfeed or wherever said the show was alt-right propaganda. Million Dollar Extreme’s flashy voidness of meaning was too threatening to the parallel, but carefully masked, void at the heart of mainstream industry and values. But, as Hyde tweeted on January 22, “Obama awards the Purple Heart to Bangbus on his last day in office.” That is to say: this great nation’s brave producers of video culture, and the sacrifices they make on our behalf, will never be forgotten.

19

American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson

Created by: Scott Alexander & Karaszewksi

[FX]

Ryan Murphy’s shows are typically known for their unpredictability and excess, but the first installment of his newest project, American Crime Story, offered viewers something different: a restrained take on true crime that has become part of our cultural fabric. The People v. O.J. Simpson tackled complex issues at the intersections of race, gender, and class, touching on everything from Hillary Clinton’s campaign to the Black Lives Matter movement while still leaving room for more than one satirical wink to the impending rise of our Kardashian-saturated mediascape. Murphy’s soap-opera sensibilities have always allowed his actors to shine, and American Crime Story was no different. Sarah Paulson played ill-fated prosecutor Marcia Clark with empathy and bright-eyed intelligence. As Clark’s co-prosecutor Christopher Darden, Sterling K. Brown exuded a naive intensity and vulnerability. Together, their chemistry lit up the screen. The show never forgot it was telling the story of real people, whose frustrations, humiliations, and small triumphs were all too real, with far-reaching consequences. The People v. O.J. Simpson wasn’t just a telling metaphor of our current moment, it was compelling television at its finest, with the power to leave its audience as raw and exposed as its characters.

18

War & Peace

Created by: Tom Harper

[BBC/A&E]

In the third episode of Tom Harper’s exquisite adaptation of War & Peace, the meek and open-hearted Pierre Bezukhov (Paul Dano) squares off in a duel against Dolokhov (Tom Burke), a trained soldier and notorious scoundrel. Bezukhov scores a lucky shot, but his one-time friend won’t go down so easy. Animated by sheer, white-hot hatred, Dolokhov props himself up, prepares to return fire — and misses, collapsing face-first into the snow. Seeing his own life spared and his foe vanquished, Bezhukov’s reaction is not exultation, or even relief; he mutters a single, self-excoriating word: “Stupid.” The image of 19th-century Russia that Tolstoy offers us is circumscribed by such acts of civilized, ornamental violence. It provides an exquisite backdrop for his characters’ small acts of pettiness and cruelty, but also mercy, generosity, kindness… the constant cycle of failure and renewal, epiphany and loss of clarity that makes up the human experience. And while we may get swept up in the grandeur of the Napoleonic wars, neither Tolstoy nor the filmmakers adapting his magnum opus ever allow us to lose sight of the futility of violence and its distraction from the serious, sacred business of living.

17

Broad City

Created by: Ilana Glazer & Abbi Jacobson

[Comedy Central]

There is no show without their friendship: A love that refused to be one-note or predictable, even as the Abbi and Ilana caricatures embarked on more and more surreal excursions into sitcom conventions. Swapping identities, juggling multiple dates in one night, returning the fundraiser money you inadvertently stole from a childhood friend. From the premiere’s bathroom overture to the climactic terror at 1,000 feet, Broad City’s third season was its most ambitious and refined to date. As the set pieces and storytelling reached new heights (and changed locations), the show remained grounded in the free chemistry between its heroes, whose frankness about their past humiliations, creative insecurities, secret desires, and adoration of each other invited us into a mundane that felt alive and ready to burst. Adventures that screamed, “Live a little!” It was in the recurring fake wokeness of Ilana, Abbi’s pivots from humility to egomania, and the way they surprised each other in almost every episode. In a New York minute, Broad City would tackle abject millennial woes with a politics of precarity, double over into poop jokes, and remind you to call your best friend, even though it felt like she was already sitting right next to you.

16

HyperNormalisation

Dir. Adam Curtis

[BBC2]

Our own Joe Hemmerling most accurately defined HyperNormalisation as a more woke version of Michael Moore’s work, though that’s precisely what makes this nearly three-hour long, archival-footage-heavy documentary one of the most 2016 things to hit a TV-screen last year. Indeed, Adam Curtis charts the last four decades of Western politics to expose the forces that shaped the world we live in: a bewildering string of events that have prompted us to accept the “normality” of the simplified version of reality that economic and political operators have surreptitiously built. The British filmmaker articulates such a premise through shockingly plausible conspiranoia arguments (i.e., Henry Kissinger, Jane Fonda, and Felix Rohatyn inventing vaporwave), denouncing media manipulation while indulging in a fair bit of it himself as he leans on lots of stylishly-presented ambiguity, peaking with Trump’s election in an epilogue that can’t help but feel tacked-on despite its timelines. Nevertheless, Curtis manages to negotiate the distance between Gazelle Twin and Alex Jones, Jean-Pierre Gorin and Dinesh D’Souza, in an audacious filmic essay the likes of which they don’t make anymore, ultimately shaping his sketchy theses into a compelling piece of cinema.

15

Lady Dynamite

Created by: Pam Brady & Mitch Hurwitz

[Netflix]

What comes after post-postmodern? New New Sincerity? Whatever stupid label you could generate for its truly peculiar brand of subversion, Lady Dynamite has anticipated it, embraced it, and collapsed it. Grossly, it’s a metacriticism on meta media, a deconstruction of flashback narratives (Present, Past, Duluth?), a satire of surrealist comedy shows, a no-holds-barred narrative of navigating mental illness, a goddamn pterodactyl. Maria Bamford as herself not only squashes every single wall left standing from Louie, but in an unprecedentedly self-aware performance, constructs new spaces only previously familiar in our own heads; some scenes are so strange, it’s like watching a sitcom set in a mathematically impossible dimension where we’ve all solved the Jacobian conjecture, but not our own happiness. And while it stylistically takes cues from shows as diverse as Arrested Development, Bojack Horseman, and The Sarah Silverman Program, its Gestalt aesthetic feels completely uncharted. Finally, a comedy that eloquently captures the ineloquence of break down, as much a corporealization as it is a hallucination of not knowing what you’re doing… more than half of the time.

14

Veep

Created by: Armando Iannucci & David Mandel

[HBO]

Veep’s repertoire presents a perversion of our public thing, not our republic: it only suggests policy behind closed doors, alternately animating unrehearsed political performance in naked view of We the Voyeurs. It is fictional witness against the popular fallacy that public life can transcend personality, conviction, or ambition. And though the events of the show’s fifth season made a token no less, they offered a turning point and a question mark: disgraced among élites and disfavored by the public, Selina Meyer is not back by popular demand. Her lack of a true mandate, the ensuing drama and immediate downfall, were even more poignant and relatable than previous, offering not only tragic comedy, but something reflective of an incumbent American self. Yet again, this fictional District, a pseudo-Jeffersonian replica, transcended mere duplication: that of high office, of name, date, and birth, of L.C.D. demand, etc. Rather it imbued a crazed hyperbole, a deliberate hysteria un-associated with the conventional or applied, to the already hyper-normal. Third-rail in full grasp, Veep’s fifth season presaged our post-electoral theater of politics-as-not-usual: unattached, unremitting, unrepentant — though never unamused.

13

OJ: Made in America

Dir. Ezra Edelman

[ESPN]

Sports can be as fiery a talking point as religion or politics. When two of the three intertwine and become a national talking point…. well, yikes. 2016 saw a Super Bowl halftime show with Black Panther imagery, and six months later, a 28-year-old quarterback sat down during the National Anthem. It also saw needed reminders that race and games are not newfound bedfellows; in a year beset by #FakeNews and a troubling conflict between emotions vs. facts, sports journalism had quite a year. Credit is due to ESPN and its triumphant 30 for 30 documentary series for giving directors like Spike Lee and Ezra Edelman freedom to encompass some touchy shit. While Spike’s Lil’ Joint 2 Fists Up spent one hour chronicling the ascent of Black Lives Matter and its impact on the University of Missouri’s most prized aspect — football — Edelman’s OJ: Made in America took over seven. It was one of two binge-ready miniseries (the other being the campy dramatization The People vs. OJ Simpson: American Crime Story, or: “The One Where OJ Totally Did It”) about the first of many times a nation would unite to binge-watch the news. As Edelman tactfully demonstrates, the shitfuck-crazy “Trial of the Century” was never cut-and-dry, proving wrong those who assumed former QB/spokesperson/actor OJ Simpson, accused of murdering wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ron Goldman, would be found guilty. To understand the whims of “how could a jury possibly come to that decision so quickly,” Edelman traces not just Simpson’s arc from birth to Hertz to The Naked Gun, but the black Los Angeles projects he grew up in and later disassociated from. Culling archival footage going back half a century, as well as interviewing key names like detective Mark Furman, prosecutor Marcia Clark, and those formerly near and dear to Juice, Made in America is remarkable in demonstrating how a group of people, after years of being treated like dirt, could vote based more upon “fuck yous” than facts.

12

Horace & Pete

Created by: Louis C.K.

[Pig Newton]

After ditching the innovative and critically acclaimed Louie after five seasons, Louis C.K. returned to television like a comic to a fresh hour of stand-up. Reinvigorated and inspired, specifically by Mike Leigh’s early televised plays, Louis’s surprise release of the ineffable and achingly humane Horace & Pete saw him breaking completely free from network constraints. It challenged not only television’s often slick, streamlined aesthetic template with a strikingly minimalist style and loose structure, but also its methods of promotion, distribution, and standardization of length and format, releasing episodes of varying run times for purchase on his own web site with no details about when and how many more new episodes would appear. What could’ve been a mere stunt instead became one of the year’s most daringly personal and emotionally devastating television events with more empathy in its self-contained 10 episodes than most shows have in 10 seasons. Using brilliant performances from Steve Buscemi, Alan Alda, Edie Falco, and Louis himself, Horace & Pete transformed its two small sets — a bar and an apartment — into depressingly comic worlds that were microcosms of our own. Its touchingly melancholy examination of a family damaged by generations of emotional abuse deftly weaved in astute observations on race, politics, sex, and death, shrewdly reminding us that, although the past is seen through rose-colored glasses, it is the present we must reckon with.

11

Bojack Horseman

Created by: Raphael Bob-Waksberg

[Netflix]

In season three, filled to the brim with ressentiment yet unwilling to really face his own culpability in how wretched a person he’s become, Bojack Horseman (voiced heartbreakingly and hilariously by Will Arnett) turns his focus outward to find ways of becoming OK with himself and his place in the world. The genius of the series’ most recent season dwelt squarely with how bravely it confronted the things about its characters that would normally turn off an audience. As the characters we’d had a chance to grow with became increasingly desperate and despicable, the fine line between ridicule and a forlorn honest accounting of personal failings started to blur, and those with the resolve to stick with it to the end enjoyed some pretty indelible storytelling along the way. Season 3 also featured one of the most remarkable 25 minutes of animation we saw this year, featuring an entirely silent rumination on the discomfort with the possibility of connection felt by one who has so completely othered himself from those around him. Does it seem as weird to you as it does to us that the most human character on American television right now is a talking horse?

10

Baskets

Created by: Louis C.K., Zach Galifianakis & Jonathan Krisel

[FX]

For absurdist half-hour serio-comedies, the combination of C.K., Galifianakis, and “Tim & Eric” collaborator Krisel seemed too perfect a creative talent storm. The post-Golden Age TV connoisseur’s internet-honed backlash raised legitimate questions. Will it actually be LOL funny or another occasionally-we-can-smirk-at-this character drama? Can Galifianakis overcome his post-Hangover hangover when he’s not flanked by potted plants? Will it be too weird or not weird enough? How much was C.K. really involved considering he’s got, you know, his own signature show and an ambitious self-distributed digital series? And, wait, does it matter that it’s on FX and not FXX!? In the end, Baskets answered most of these questions. Amid all the talk about gender identity, Louie Anderson’s simple human portrayal of Ma Baskets traded the easy laughs that defined cross-gender comedic performance into a complex portrayal of life’s disappointments and idiosyncrasies that defined the show. Just as vital was Martha Kelly’s Martha, a painfully acute portrayal of normalcy. Plus, the show’s Bakersfield setting was a nice reminder that there’s a whole lotta country outside of L.A. and New York.

09

Black Mirror

Charlie Brooker

[Netflix]

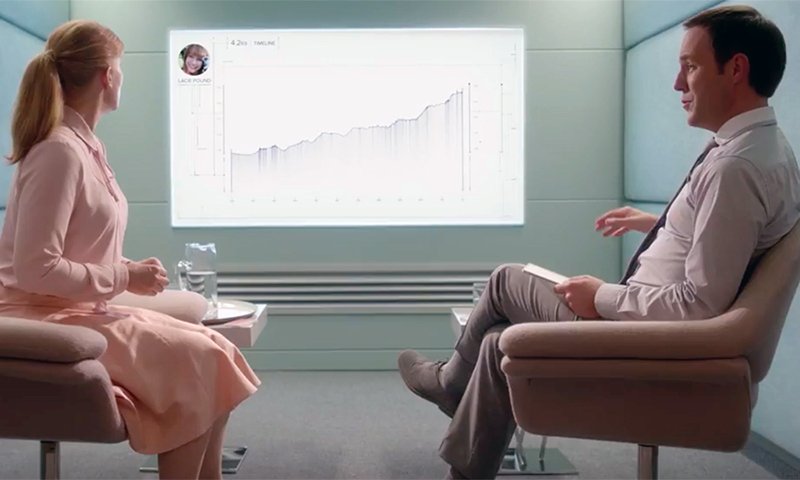

While smooth for the most part, Black Mirror’s transition from its first two seasons — as a BBC-produced darling, into its third as a bingeable Netflix product — wasn’t without a few dings. Still easily one of the most exciting, original, and oftentimes intoxicating series out there, Black Mirror’s third season seemed to push more into the grotesque, overinvesting in fx-shock tactics at the loss of more subtly moody, twisted narratives. But the stakes were incredibly high: the great ambition of Black Mirror is that, as an anthological series, it must create a new reality for every episode, one where a single aspect of technology (whether already in existence or speculative) wreaks havoc on society. All considered, 2016’s Season 3 (to be followed up by another season this year, also on Netflix) is still superb social-technological commentary, expertly crafted to make you gasp, scream, or cry (sometimes even, I swear, laugh). And not all six episodes are entirely doom and gloom — “San Junipero,” while melancholic and tragic in its own right, is an enlivening tale of second chances via a virtual, paradisiacal purgatory. Black Mirror is science fiction that matters, not because of the near-futures it imagines, but because it so eerily resembles our present — and it may be too late to go back.

08

The Night Of

Created by: Richard Price & Steve Zaillian

[HBO]

In a lot of ways, this eight-part miniseries was just another crime drama, with suspense around the guilt/innocence of a suspect and the colorful bureaucratic and emotional rigors of those involved with the case. Replace John Turturro’s foot problem with constant nips from a Pepto bottle or noisy nose blowings and he’s pretty boiler plate. Jeannie Berlin’s tough, cynical prosecutor with the itchy conscience is also familiar. Yet what both actors brought to their roles was everything. Everybody in this somber, sordid tale crackled with life. Bill Camp wasn’t just the retiring-cop-with-the-lingering-doubt guy, but a real thinking person with no bluster or platitudes to sort him for the viewer. Riz Ahmed played the ostensible innocent without conveying saintliness. His countenance was ever brave, yet pulsed with heartbreaking fragility (that rare thing of a tempered star-making turn). The masterpiece that was Deadwood was simple and ornate, but assailed with an unparalleled cast and dialogue, roundly revitalizing its quaint, place-holding tropes. What Deadwood did for the western The Night of managed to do for the impossibly, unflaggingly ubiquitous crime procedural — proving that sustenance, if applied carefully, can still stick to our towering, immovable genre bulwarks.

07

Silicon Valley

Created by: Mike Judge, John Altschuler & Dave Krinsky

[HBO]

A luau at Alcatraz, a fight with a robotic deer that just got run over, Dinesh’s gold chain. These are just a few examples of some great instances of comedy in the third season of Silicon Valley. There is one moment that always springs to mind first, however, when I contemplate this season of the show: In the second episode, Richard Hendricks (Thomas Middleditch), our hero, confronts his new boss, Jack Barker (Stephen Tobolowsky), at his horse farm. Barker is there to oversee the breeding between two horses. The scene is hilarious in how incredibly uncomfortable it is, due in large part to the fact that while the two characters try to have a serious conversation about the future of their company, graphic horse sex is going on behind them. Now, a few years ago, I never anticipated that this show would be the thing that exposed me to what an erect horse penis looks like. In some ways though, it makes perfect sense. Silicon Valley is often at its best when it is at its most ridiculous, and what better way to satirize an actually ridiculous place like Silicon Valley than to ratchet up the absurdity as high as standards and practices will let you take it. If that’s not comedy, then what is?

06

Stranger Things

Created by: The Duffer Brothers

[Netflix]

How do you really define a decade in pop culture? How is it possible to fathom and re-portray what was popular, what was cool, and what still holds resonance beyond the swarm of “what influenced me most as a kid” lists on Facebook? It’s tricky to say, other than through tackling personal experiences, news articles, and “historic” events, and by making your way through the necessary “relevant” album and film post-mortems. But at least that allows you to stumble upon a supposed aesthetic that crystalizes tendencies that fell across the span of a short few years, and The Duffer Brothers’ wiley and measured encapsulation of an estranged 1980s parallel perfectly suited the story that they were keen to tell. This was a tale of family, of trust, of dependence, and of a secret society, and within that stylized chrysalis, Stranger Things documented more than just an arrangement of disjointed family relationships (which Winona Ryder brought to the fore in her character, Joyce). It also brought a sense of curiosity that existed before the digital revolution. Sure, these episodes were haunting, daunting, and riddled with suspense, but they also tackled broader topics while taking optimum care in their exploration of a 10-year span that has been glorified, vilified, and despised from the very moment it came to a close.

05

Mr. Robot

Created by: Sam Esmail

[USA]

For a show with a narrator as unreliable as the stories told by its corporate villains, it’s amazing how Mr. Robot managed to sharpen its critical attacks this season. Harboring all the twists and turns expected of high-profile dramas, Mr. Robot ramped up the cautionary tales for progressive and insurgent movements, propping up political allegories and cultural corollaries to our own fucked-up world while blurring the fictitious with our contemporary moment via E Corp, Enron, Dark Army, Occupy, fsociety, Anonymous, Snowden, Elliot, etc. Through it all, the show maintained the creeping fervor and horrifying thrust of the first season, the filmic pastiche and quotations this time exaggerated to even more surreal ends through long, hallucinatory sequences favoring kineticism over plot. This season’s masterstroke, however, was to zoom out of the corporate paranoia and highlight, both on the show and in our own lives, the global oppression and exploitation also imposed by state violence, conflating the spheres of capital and the state in complex, multifaceted ways. Here, the show sought to temper the frailties of the human condition with the revolutionary possibilities of technology, couching the personal-is-political (the parents of the show’s protagonists, Elliot and Angela, were victims of a chemical spill — sound familiar?) with broad messages about mental health, accountability, rhetoric, and mediations to power. Mr. Robot is simply the most critical, high-stakes show on TV, aimed brilliantly at those who, as Elliot put it, play God without permission.

04

Game of Thrones

Created by: David Benioff & D.B. Weiss

[HBO]

Our time in Westeros is running short: in 2016, showrunners announced that there will be just two more seasons of everyone’s favorite family-friendly fantasy drama (just kidding, don’t let young children watch Game of Thrones). The antepenultimate season perfectly encapsulated what makes GoT great TV: We got answers to some of our long-standing questions, sobbed over the deaths of beloved characters, rejoiced in the comeuppance of hated ones, and cheered for our preferred House in carefully-constructed battles. Sure, there were some misses (the dead silence that Tyrion faces when trying to teach Grey Worm and Missandei how to crack jokes pretty much mirrored exactly what was happening on the other side of the screen), but the massive hits (Dragons! Wildfire! White Walkers! “Hold the door!”) more or less made up for those. And as storylines became intertwined and the ties that bind the main characters became more evident, the various chess pieces that make up the Game of Thrones universe began to fall into place, setting us up for what will surely be two more incredible, history-making seasons of television.

03

Atlanta

Created by: Donald Glover

[FX]

In the embarrassing tradition of rough critical-consensus adjectives ironing out their own usefulness, “peak tv” is now a style. It’s basically a snobby genre, à la “important” or “prestige” film. The draw still boils down to sex, violence, and jobs, but things are generally quieter, slower, and oh so portentous. Despite its crass-slingin’, bro-centric target demo, FX has been an impressive host to the more surprisingly winning content of this sort, and they truly did peak with this perfectly pitched marvel of a show. Donald Glover and his creative team put us in a space that, while utilizing that familiar peak minimalism, structurally surprised without ever losing its lithe tonal refinement. This first season clicked as misadventures loaded with biting satire, but enraptured with intricate, loving human detail. Earn, Van, Darius, and Paper Boi all left indelible, endearing impressions, and the secondary characters, often their quarry, were nonetheless shrewdly observed. Claims of the “cinematic” in TV are often overblown, but Atlanta’s transportive, just-this-side-of-dreamy direction frames its deft social critique/character study in such a seamless way that it feels like the most expansive visual storytelling in years, peak or plummet.

02

The Girlfriend Experience

Created by: Lodge Kerrigan & Amy Seimetz

[Starz]

Women’s work necessarily balances — between eggshells — tradition and meek innovation. Quilting is variation stitched together by sameness; blowjobs, sameness punctuated by variation. Throughout The Girlfriend Experience, these binary codes play out in gloriously narrow fashion. Directors/Writers Amy Seimetz and Lodge Kerrigan take an entire aesthetic whole from Steven Soderbergh’s 2009 film of the same name — unrelentingly voyeuristic distance shots of interiors and the buzzing of office lights — but use their half-hour TV series format to foreground the redundantly transactional nature of sex work in ways impossible for cinema’s slant toward spectacle. As student/law firm intern/sex worker Christine Reade, Riley Keough (who also killed it in her supporting role in this year’s American Honey) likewise lit up the screen in the most boring of ways, showing just how staid fucking for money — at least on the selling end — can be. The narrative arc follows the thoughtful, meticulous acquisition of dollars, not the predictably erratic pattern of seduction or cumming, as Reade successfully navigates yachts, expensive hotel rooms, abandoned mansions, and the men who own them: she’s good, we gather, at her work (wink wink), but more skilled as the manager of her business slash self (solemn nod). Despite — or yes, because of — being one of the most explicit shows of the year, The Girlfriend Experience was no empty pantsuit, deploying sex-as-formalism to hold its own against 2016’s most vexing debates around gender and power.

01

Westworld

Created by: Jonathan Nolan & Lisa Joy

[HBO]

“Cultural phenomenon” is hardly the first descriptor to spring to mind when one thinks about the original 1973 Westworld film. Michael Crichton’s campy exploration of an android takeover of a Western amusement park remained largely forgotten outside cult circles. Similar to countless other outlandish cinematic experiments from the 1970s, Westworld was mostly remembered as yet another oddity of unfulfilled potential rather than as a forgotten flawed masterpiece. HBO-induced revisionism may now change this perception, however.

It came as a surprise to many when HBO announced it was in the process of producing a Westworld TV show. Late-night TV nostalgia had still left fond distant memories of the original film, and the hype train was soon boarded, especially after the first released teasers and cast announcement (Anthony Hopkins, Ed Harris, and Evan Rachel Wood have all given career-defining performances this season). Crichton’s original concept remains fascinating, but not only was the original film terribly outdated, the few spin-offs from the original story were either underwhelming or straight-up silly (a 1978 sequel titled Futureworld and a 1980 short-lived TV show with only three episodes aired before cancellation).

Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy’s Westworld, however, is a different beast entirely. An elegantly ambitious work, it was as painstakingly fashioned as an intricate puzzle game, which led to a richly interactive communal experience with its viewer base. Contrary to the binge-watching phenomenon, Westworld made a strong case for the seemingly outdated weekly TV show format, wherein every week spectators would endlessly debate new theories or further illuminate old ones. This format worked so well because, unlike shows that prompt similar viewer experiences with wild speculation (Lost, Game of Thrones), Westworld actually provided narrative material and imagery to support fan theories. Parallel to the robots seeking to escape their programmed slavery, the pieces were there all along for us to assemble. The maze, the holy elixir of conscious life constantly referenced throughout the season, exists both for the hosts and for the spectators.

Among the many noticeable and important changes from the source material is the terminology. The robots in the park are called “hosts” in HBO’s Westworld, a much more fitting term for the repetitive and excruciating humanization process that the machines must undergo before offering a truer-than-life experience to the park guests. Repetition plays a central role in Westworld’s narrative, as well as in the hosts themselves. While they experience their lives within their predetermined narrative loops, the audience witnesses numerous apparently duplicate scenes, in which each new repetition reinforces an evolving meta-narrative. At every break of dawn, the hosts’ programmed AI narrative determines their personal stories, how they should behave, feel, and perform. In spite of all their technological complexity, however, their ultimate objective in artificial life is painfully mundane and exasperating: to fulfill the fantasies of the human guests, which, as human fantasies often go, are grounded in the immediate satisfactions and pleasures of violence and lust. Violent delights have violent ends: a recurrent prophetic statement in Westworld (and a nod Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet) that signals the ultimate price we must pay for our egoistical, anthropocentric search for gratification by way of reckless eroticized violence.

There is something God-like in creating a fictional character, and Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins), the park’s larger-than-life mastermind, certainly appears to derive sadistic pleasure from creating pain out of nothing, watching his hosts eternally endure whatever tragedy his personal whims dictate. Ford’s obscure personal vision even inspired think pieces on the ethics of artificially constructed pain. Roxa Luxemburg once said that those who do not move, do not notice their chains, and ultimately, in a somber twist of events, continuous incessant pain becomes the only path for the hosts to perceive their condition, to regain class consciousness and overtake the means of their own production. But the enduring question remains: to what and where can they ever actually hope to break away to? The loop becomes static, the story eternal, their fates shackled.

Season 1 left us with many unanswered questions (and sadly season 2 is scheduled to return in 2018). Westworld, however, does leave a defining mark in a year that witnessed a slant toward the experimental in TV (another significant example was the flawed, yet deeply enthralling The OA). We are going to repeat it all again this year, no doubt, yet something has been broken away. Our loops slightly changed. And we owe much of this to the sacrificial pain of the hosts of Westworld.

Welcome to Screen Week! Join us as we explore the films, TV shows, and video games that kept us staring at screens. More from this series