Why would Brian Eno choose to open an electronic music festival talking about neoliberalism? The superstar producer was invited to give the inaugural lecture at Sónar 2016, the Barcelona-based festival that describes itself as a crucible for music, creativity, and technology. In its 22nd edition the event that started as a haven for electronic and experimental music doubles down as an art fair, a professional convention, and a technology summit.

In short, you’re as likely to see start-ups, trade talks, and music gear demos in its lineup as some DJ or any other sort of musician. It would be hard to find a person who embodies such a boundary-blurring mixture better than Brian Eno. Pity that the Eno we got was a self-styled intellectual who delivered a rambling speech halfway through your standard TED Talk and a John Oliver segment. Dropping vague references to Noam Chomsky and Barbara Ehrenreich, criticizing the privatization of the U.S. jailing system and the type of tests his girlfriend’s son must take to enter the university, Eno decried a society where economic worth has become the ultimate goal, obliterating art in the process and hence stripping us of a way to make sense of the world, to learn, debate, and exchange knowledge. Not that it isn’t true, but do we really need Brian Eno to repeat so trite a spiel? He surely has more interesting insights to share.

Though Eno set the tone for a festival described from the outset as “politically charged,” he did not represent the breadth or insight of most of the artists showcased in 2016’s edition of Sónar. In light of the astonishing diversity of the lineup and the uncompromising performances on immigration, violence, and gender identities the festival featured, we can depict the three-day event as a continuous dialogue about the many ways to frame our contemporary communal experiences. Something most evidently befitting ANOHNI’s current work or Niño de Elche and Los Voluble’s examination of “all types of borders,” but which also is true about Swedish rap outsider Yung Lean’s path to stardom, Kelela’s extravagant reimagining of soul music, Ata Kak’s bizarrely personal brand of Ghanaian pop, and even applies when all you care about is jamming to “Blue Monday” on a Saturday night out with your buddies.

In Outside

Taking place over three days (June 16 to 18) with clearly separated day and night sessions, Sónar embraces the complementarities of such a bipolar character. Sónar día, the daytime half of the festival, is mostly held outdoors in the very heart of Barcelona. Sónar noche, on the other hand, stretches from dusk till dawn inside gargantuan hangars located closer to industrial silos than Sagrada Familia. While workshops and business conferences are held during the day, the night event has DJs playing next to a bumper car ride. The headliners usually appear in the evenings (Jean Michel Jarre, New Order, Fatboy Slim, Skepta, and James Blake in 2016), with the smaller daytime stages hosting upcoming acts, more challenging multimedia projects, and musicians from exotic backgrounds (Alva Noto, Danny L Harle, Mikael Seifu, Nozinja, and OPN in the current edition).

With 80 acts taking the stage during the day alone, it is hard to pick a thematic driving line. However, the recurrence of Afro-Caribbean rhythms — in various states of cross pollination — is striking. There’s a curious symmetry to a festival that lifts its curtain with Mad Professor playing dub classics and sees the last punters out to the beat of the Lord-Finesse-sampling “The Rockafeller Skank.” Both bookends resonate with other acts who bend their root genres to materialize some form of personal expression. That’s where we find Acid Arab’s encyclopedic voyage through spaced-out ethnic techno, Roots Manuva’s Trenchtown-bred hip-hop or Fennesz and King Midas Sound’s blurring of trip hop and ambient music.

Still, one couldn’t have anticipated that the show truest to the idea of merging tradition and innovation would be the one by an outré Ghanaian artist. Unearthed from bootleg obscurity by Awesome Tapes from Africa, Ata Kak’s music was recorded in 1994 but still sounds mystifyingly futuristic, as original as it is outlandish. Backed by a full band, Ata Kak owned his afternoon slot with an absurdly fun hiplife set. So dubbed because it mixed highlife — a jazzy reimagining of African folklore — and 80s synthetic beats, the live version of the genre finds the Ghanaian rapping with such cool ease that his trademark scat-by-the-way-of-glossolalia vocals sparkle with a charm impossible to resist. It cannot be a coincidence that so winning a performance came from a man who taught himself how to program a beat after spending time in Canada and Germany, trying to channel the funky aura of Ebo Taylor with Grand Master Flash and a rudimentary drum machine as a medium. It goes to Sónar’s credit how much it tries to create the conditions for that type of interactions to take place, or at least for its audience to be aware of them.

Build Your Outside

It makes sense to question the reasons for a European festival to feature artists from developing countries, who in most cases are not even professional musicians back home. Acknowledging that as a discussion to be had, Sónar’s interest in global sounds goes back to its inception. It was in Sónar where the international careers of Konono Nº 1, Bomba Estéreo, and Omar Souleyman broke outside their native countries. In tune with that vision, the 2016 edition was quick to embrace the work of artists who question the many discriminatory mechanisms operating in the world today. The highest profiled of these must have been ANOHNI, who presented Hopelessness alongside Daniel Lopatin and Hudson Mohawke. Essentially faceless on stage as she covered her whole body in a tunic, on a screen behind her ANOHNI projected the faces of several women lip-syncing to her most recent tracks. Thus, the Sussex-born singer stressed the human urgency of a material that on record often runs the risk of registering as inelegant or patronizing in its clamors.

On the other end of the scale we find John Grant, who has perfected a mixture of auteurish pop, cheeky lyrics, and funky rhythms. However, that does not imply a levity aiming below the self-serious acts joining Grant on the festival’s roster. Through three remarkable albums the Iceland-based songwriter has chronicled the exploration of his sexual identity and struggles with mental and physical health, pouring these into songs rendered with lots of black humor. IGrant alternated between his elegant balladeer persona and a promiscuous dance floor prowler, presenting the still recent Grey Tickles, Black Pressure to a crowd comprising people in Patrick Cowley, Macintosh Plus, and Pet Shop Boys t-shirts — talk about knowing how to read an audience.

Kelela’s mid-afternoon turn was also a display of talent, personality, and self-confidence. Splitting her own show between ballads and more lively cuts, the singer knew she had what it takes to fill an otherwise bare stage. Joined by a DJ discretely standing in the back, nixing any choreography or sophisticated light effects, Kelela put her fantastic voice up front and it paid off. Aware she had kept the audience attention through 20 minutes of slow cuts, she mocked those who tell her not to play ballads in festivals. Nonsense. Emotion is at the heart of any sort of soul music, even one Bok Bok, Nguzunguzu, or Jam City twist and remake at will. Later, as the “turn up” part of her show reached its climax, Kelela told us how just four years ago she was still working as a telemarketer, the idea of playing a festival in Spain not even a remote possibility. Convinced that it is up to us to go out there and make things happen, she encouraged the audience to “build their own outsides.” It was not an accidental phrasing, perhaps more meaningful to the festival than Brian Eno’s whole hour of pseudo-progressive fodder.

Out Inside

If the balance between a sturdy rhetoric and electronic music strikes you as odd, think again. When the genre’s forbearers started their careers most people did not even consider the resonators, samplers, and computers they insisted on playing to be musical instruments. With one foot in the avant-garde and the other in science, these artists needed a relentless confidence in their discourse in order to carve a niche for themselves. This is true even for people whom commercial success was not hard to attain, as is the case of Jean Michel Jarre — a man who might have sold several millions of albums but rightfully claims to be a heir of Pierre Schaeffer, the lab-dwelling father of musique concréte.

The French icon was one of Sónar’s proudest catches, for Jarre had chosen the festival to premiere his latest show. This might not sound as a big deal unless you are old enough to recall Jarre’s heyday, which saw him play to some of the largest crowds ever assembled and stage laser extravaganzas at the pyramids. Though obviously subdued in comparison, Jarre’s Sónar set tried its hardest to impress. Of course, there are few tricks available to him now that others have not used before. Namely, the massive movable screens he set around the stage were employed to better effect by Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails. Similarly, Jarre’s newest music marries the vintage theatricality of prog synthwork with the bombast of EDM but cannot achieve the cathartic potential of either. Even his much touted Edward Snowden cameo fails to land when attached to a guy who conducts himself on stage with the self-importance of an autocrat. Jarre does play a sick keytar solo and is not above bringing out his famous laser harp, yet he disappoints all the same. It’s a repeat of what happened with his recent Electronica albums, stacked with amazing collaborators but producing forgettable if not downright pungent cuts. We are not exactly asking for good taste of the guy who wrote Oxygène. On the contrary, embracing his megalomania may actually be what Jarre needs in order to make his shows memorable again.

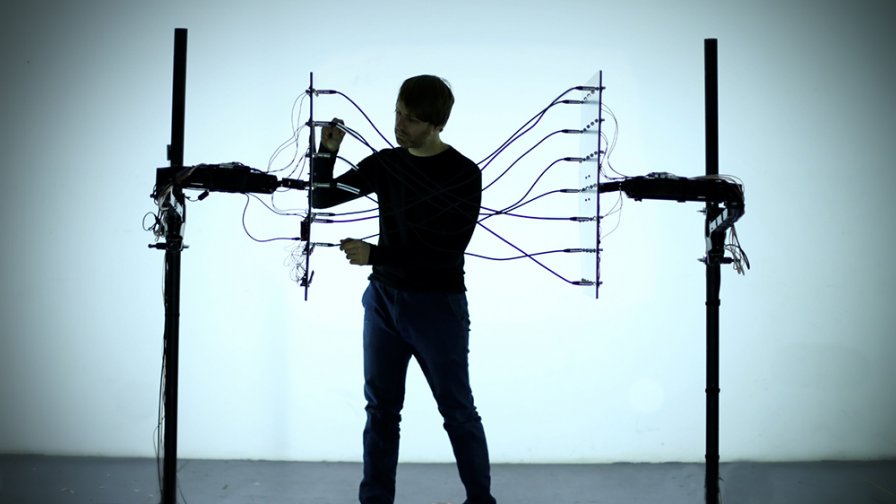

In a smaller scale, the artists signed to Raster-Noton traverse a path similar to Jarre’s. The German label is turning 20 this year and decided to celebrate by hosting a showcase at Sónar, honoring its long-standing relationship with the festival. Instead of an old fashioned birthday party, Alva Noto, Ryoji Ikeda, and Olaf Bender played three shows as stepped in the label’s emblematic minimalism as they were informed by science. Hence, they peppered their visuals with patterns recalling DNA helices, electric bolts, and spectral lines, with their music taking the sound of electric appliances and heavy machinery to bend it into brutal shapes we still find familiar. It’s a cue Martin Messier’s FIELD show takes as well, with the Canadian channeling a mad scientist while he plugs and wires two magnetic plates, enough for him to conjure an odd musicality.

However, none of them come close to Daniel Lopatin in terms of translating some abstract ideas, a concept, into a show. In full Garden of Delete mode, the Oneohtrix Point Never we saw at Sónar found Lopatin joined by Nayte Boyce on guitar, who donned a black-metal T-shirt to trash a heavily-processed Steinberger. With Lopatin taking care of some very distorted vocals — I can only describe the way he sounded as ‘death-metal chipmunk from hell’ — the duo tackled G.O.D.’s post-internet angst-metal with terrible aplomb. And if the music was not fucking with your psyche enough, OPN threw in strobes so powerful they could blind you even if you closed your eyes and covered your head with your shirt for good measure. Of course, the visuals went deep into suburban teen horror iconography, at times suggesting Jesse Kanda riffing on a Tool video or old paranormal-flavored videogames like Hexen, among other pubescent metalhead staples like Dungeons & Dragons and H.R. Giger. I heard some people compare the experience to an afternoon in Guantanamo, others headbanged harder than in a Mayhem show. I remembered my schoolmates who used to play Vampire: the masquerade while listening to Coal Chamber. Great times, I tell you.

The Great Inside

What would an electronic music festival be without the chance to dance yourself to abandon? In its two decades of activity Sónar has perfected the art of pumping its audience with endorphins, as evidenced by the troves of people who take the festival as a synonym for unbound pleasure, going as far as throwing their bachelors parties during the event. Hell, Sónar’s night edition even has a club-like stage built within the premises, where this year Laurent Garnier and Four Tet played seven hour sets each, helping people lose their collective minds to Daphni, Fela Kuti, Carl Craig, Floorplan, or Frankie Knuckles. A selection reflective of the festival’s diverse lineup, come to think of it.

That said, it’s not like the daytime event is a dour affair. Although the weather did not help — what is considered by locals to be the unofficial start of the summer had to withstand the strongest storm of 2016 — plenty of artists were programmed to keep the mood festive through the afternoon. Danny L Harle was one of them, treating a still-soaked crowd to his signature sugary pop, dropping tracks off the recent Broken Flowers EP, his newest collaboration with Carly Rae Jepsen, and even a remix of “Call Me Maybe.” Playing shortly after Harle, Matías Aguayo took charge of drying people’s clothes out with his take on Latin music by the way of techno. That’s not entirely accurate, though. Unleashing a set both manic and sultry, we may all have gotten wet again with the steam coming off Aguayo alone.

Fatboy Slim notwithstanding, New Order must have been the biggest dance-friendly act featured in the program. At least on paper the English band were touring behind 2015’s Music Complete, their return to an electronic-cored sound since keyboard player Gillian Gilbert took a leave in 2001 (she is back now), if not the Ibiza-inspired 1989 LP Technique. In a brave gesture for a band into its fourth decade of activity, New Order’s set leaned on their new material, with the whole first hour of the show including just two oldies. And even when tracks like “Bizarre Love Triangle” or “The Perfect Kiss” appeared, they did in rearranged versions that tried to integrate them into the festival-ready hues of “Tutti Frutti” or “Plastic.” And though this meant cranking up the low end of the rhythm section in detriment of Stephen Morris’ famously clinical playing, it brought new life to otherwise overplayed cuts, with an effervescent “True Faith” as a stand-out.

Talking about symmetry, if Brian Eno was the one charged with opening Sónar 2016 looking like the living embodiment of the festival’s ideals, a band from Manchester in the middle of a late-career reunion does not seem to best synthesize the essence of the event. Except, of course, if that band is New Order. Their towering influence on all things electronic aside, the English were pioneers in the adoption of musical technology, embraced the hedonistic character of their sound without phony qualms, and found their true musical selves in the sweaty beats blasting in the Latino and gay discos of early 1980s New York. Rising from the rubble of a city in decay, superstars as they are today, few bands can claim to have built their own outsides with the conviction of New Order. Reborn in the guise of unimpeachable elder statesmen of the scene, perhaps they are the ideal inspiration for a festival about to reach its quarter of a century of existence. Would you rather have Sónar hang out with freaking Bono instead? Thought so.

More about: Alva Noto, Anohni, Ata Kak, Brian Eno, Daniel Lopatin, Danny L Harle, Jean Michel Jarre, John Grant, Kelela, Matias Aguayo, New Order, Niño de Elche, Oneohtrix Point Never