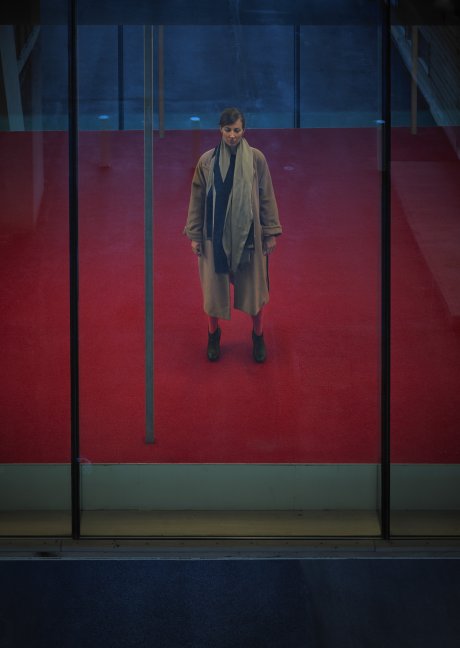

Amsterdam’s Christelle Gualdi has been creating lush synth environments as Stellar OM Source since the mid-aughts. Her early work was characterized by free, vibrant synth play, with her recent work being more structured and beat-driven. Her new EP, Nite-Glo was released this week on RVNG Intl., and it continues in this fun, challenging, highly danceable vein.

Tiny Mix Tapes talked with Gualdi about sound, silence, and everything in between.

Several artists working in the late-2000s noise/new age scenes made a shift toward rhythmic music in the early 2010s. What prompted this radical break for you?

I always felt that I could not belong to any scene. The way I make music has always pretty much been the same. I didn’t experience any radical break. You gain more knowledge, and your skills become more complex. There is also a contemporary need to categorise and theorise artistic expressions.

Holly Herndon once stated: “It is amazing the things you can get people to listen to if you simply embed them within a 4/4 rhythm.” Nite-Glo is the first time you’ve utilized a 4/4 kick at this scale, and feels like the result of a long series of musical explorations over several years rather than something to take for granted as a starting point. What’s your relationship to 4/4?

I’ve been using 4/4 kick for many years. A 4/4 kick is indeed just one ornamentation in what I compose. As you mention, it is definitely not a starting point and it does not inform what I produce. It has the power of disconnecting the critical mind, and the comment of Holly is exactly perfect.

It’s much easier to stay within the comfort of those skills, but for me, it was missing much at some point. That was that unlearning process. Improvising is something I always looked at as the highest skill in music.

In a lot of ways, Nite-Glo feels pretty stripped-down compared to Joy One Mile. Was this a conscious decision on your part?

The tracks on Joy One Mile have longer history than the Nite-Glo ones, which are more straightforward. There are variations on a theme. Similar to a Quatuor à cordes in its form.

You’ve previously spoken of your formal musical training as something you had to “unlearn” in order for your own music to grow. What did this process of “unlearning” entail? Was it a conscious effort? Is it distinct from “learning”?

You have to learn to integrate, in your work, intuition, risk, and emotion within your palette of technical skills. It’s much easier to stay within the comfort of those skills, but for me, it was missing much at some point. That was that unlearning process. Improvising is something I always looked at as the highest skill in music.

What do you think is the role of the physical musical object (LP, CD, etc.) at this point in time?

Capturing ethereal emotions while we all experience life way too fast.

You’ve mentioned your upbringing in the suburbs and the negative effect that had on you. Growing up in the suburbs can condition you to accept the banal as normal. How were you able to overcome this? Is it something one constantly has to be vigilant against?

It had actually a positive effect on me. And I grew up in the least banal suburbs, home of architectural experiences.

You’ve previously talked about the need for silence, the joys of silence, the need for ears to rest. We walk into restaurants, stores, down the street, and there’s music playing almost constantly, even in environments where it’s not at all necessary, such as a home or workplace. Why does our culture feel this obligation? What effect does this lack of silence have on the way we experience sound?

I think it flattens our judgement of sounds, and for music to become background, it has to be very undisturbing as well — i.e., very dissolved content. Our culture might want this in order to think less, to notice less. Silence is scary for a lot of people, because you are just left with yourself. But this is the ultimate freedom. And it would help sounds to regain way more power in our lives.

I like to think as a free-jazz musician living in 1969..

Does hardware (physical) have any inherent advantages over software (digital)?

The more limitations and constraints, the more creativity. Personally, I don’t like that music making becomes a visual thing behind a screen. Using instruments are what music composition is about. And you can add to this any other devices which are not visual.

You’ve mentioned that you draw a lot of inspiration from jazz. Typically jazz is made by multiple instrumentalists playing one acoustic instrument each, yet your setup is one person playing multiple electronic machines. How do jazz influences manifest themselves in your work?

Through attitude. I like to think as a free-jazz musician living in 1969.

One thing that’s remained constant from your earliest CD-Rs to your latest EP is the way you create environments — your tracks feel like worlds to wander through rather than strict linear progressions. Do you feel that your work as an architect influences the way you compose music?

I need to compose music as a way of traveling. The aspects of multiplicity relate to architecture. But the same way with cinema too. At the end, it all comes down to life.

More about: Stellar OM Source