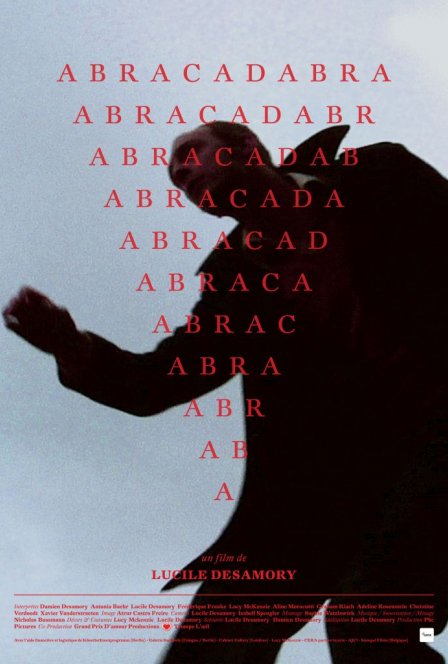

Lucile Desamory’s Abracadabra cites the Saki (aka H.H. Munro) short story “The Open Window” as its inspiration, though this source material is tenuous at best. Towards the end of the film, the blank slate protagonist Damien (Damien Desamory) meanders into a scene drawn from that work after inexplicably traveling through time (or perhaps the fictitious world of the material itself, as suggested by a character reading a volume of Munro’s work in the sequence). Desamory, a Belgian artist and filmmaker, uses the dark surrealism of David Lynch’s work as her real artistic springboard. Working on a Kickstarter budget, Desamory’s feature debut follows Damien as he encounters a spectral intruder that leads him to a strange trio of Christian women and the aforementioned trip into Saki. The inciting incident for Damien’s trip down the rabbit hole is a rare Scrabble score during a friendly game, though later the board reveals the words to be nonsensical pairings of letters. Have the supernatural forces that invade Damien’s life altered the words? Or were he and his companions just playing a bizarre form of the game to begin with? The film, of course, never answers this question, though there’s a hint, or perhaps merely just a hope, that the unscrambling of those letters can reveal a sort of code for the film.

This meticulous deconstruction of narrative time and space is the kind of device that has led Lynch’s fans to obsessively pore over films such as Mulholland Dr. or Lost Highway, though it feels like similar interpretive attempts for this film might fall short. Like Lynch, Desamory effectively uses lingering static shots and darkly ambient music tones to convey an impending sense of dread. Mostly, this build-up yields little in the way of narrative, thematic or even visual payoff. The opening sequence features a hooded dwarf-like figure gliding through the streets of Brussels at night, an eerie image that never recurs, but it’s the closest the film comes to something like Lost Highway’s Mystery Man or Mulholland Dr.’s nightmare monster. Desamory also dabbles with body horror in Damien’s recurring issue of his mysteriously blackened tongue, a refrigerated brain, or a shot in which a rabbit is cut open to be butchered.

The end goal to Desamory’s vaguely narrative absurdism suggests her take on third wave feminism. An early edit shows the director’s own face fade into the face of Damien. A sketched image of the missing husband from the Saki reference depicts a woman’s profile in palimpsest over the man. In the same sequence, when the “husband” does return, “he” does so in the form of the androgynous woman (Antonia Baehr) who appears in other scenes as other nameless characters. The cultish convent Damien visits is led by Father Pierre, yet his presence is only visible through paintings on the wall, while the three women members share a separate communal lifestyle. When Damien tries to enter this space, he is thwarted, whether knocked on the head as he peers through the keyhole, barred by an insurmountable gate, or looped back through time. The overall sense is that a female order has ousted the traditional male hierarchy, a notion supported by the film’s final image of Damien disappearing through a dark space between two painted walls. There may be some meaning in those scrambled letters after all. Desamory certainly showcases her ability to frame an intriguing shot and create an effective mood. Given the minimal resources for this film, she certainly should emerge as a promising international filmmaker.