If George Bailey had listened to everything his guardian had to say, nodded solemnly, told Clarence he had a better idea, and taken his dive off the Pottersville river bridge, It’s A Wonderful Life would have had a darker ending, probably a far smaller cultural impact, and a much closer resemblance to The Adjustment Bureau. Likewise, had Mr. Smith Goes to Washington ended with Jefferson Smith giving up on his grand filibuster to settle down with Jean Arthur — because all he’d really been aiming for by getting into politics was true love — that movie would have also more closely resembled The Adjustment Bureau.

The fact that both of these classics bear close comparison to this new Matt Damon thriller is odd enough — especially given the labored mechanics of The Adjustment Bureau in contrast to the flawless craft of these earlier films — but the fact that both classics were also directed by the same man, Frank Capra, is odder, since Bureau can only stab clumsily at being the kind of movie Capra made, which were about the better world that could exist with a little more hard work and faith. Instead of an homage to Capra’s themes, The Adjustment Bureau comes off as an awkward mashing of his plots, which is disappointing given the need in American movies for the kind of solid, weighty filmmaking and creative commentary on modern life that Capra provided.

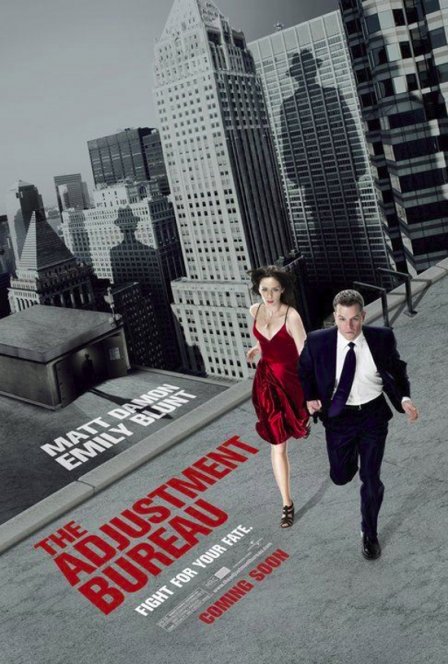

Bureau is about a young political do-gooder named David Norris (Damon), who falls in love with dancer Elise (Emily Blunt) just as he is losing his first bid for US Senate. He is so taken with her, coming, as she did, at such a low point in his life, that he starts to feel okay about not becoming a Senator. But this is not a decision that sits well with David’s Case Workers (Anthony Mackie and John Slattery), two metaphysical G-men tasked with keeping the correct path of all humanity on track. According to them, if David relinquishes his political dreams in order to settle down with Elise, he’ll never become president. And if he doesn’t become president, the world will be led astray and out of its proper trajectory, after which point it will be more or less doomed. David, however, with the same tough iconoclasm he brings to politics, disagrees with the path the Case Workers have laid out for him, so he goes rogue from his own fate.

This pretty adequately combines the intervening higher-power conceit of Life with the young-upstart Senator-setup of Smith, and with a little more polish and finesse it could have achieved the balance of corny optimism, movie-world fantasy, and beautiful storytelling that its predecessors were all about. But its polish never extends beyond its nice photography, and rather than adroitness, The Adjustment Bureau relies on one expositional monologue after another, before ending with a would-be mind-bending race across Manhattan that (at this point) seems cribbed from the final third of Inception. Even here, though, Adjustment doesn’t have nearly the aplomb of that movie, which carried off an even wilder plot with immeasurably more ease.

A movie this conceptually far-out shouldn’t have to strain so hard to make itself understood, and it definitely shouldn’t make us laugh at the plot devices (the G-men must have hats on their heads in order to transcend space and time) it’s cooked up to make its concepts work. A lot like The Happening, a movie by the guy who wants to be Spielberg (Spielberg being the only director to have come anywhere near Capra’s delicate mythmaking), The Adjustment Bureau is labored and silly where it should be straight-faced and imaginative. It’s got admirable ambition but very little idea where to go from there.