His eyes a milky haze, the blind child sings: “My heart is full of love and loving.” He smiles the way only children can.

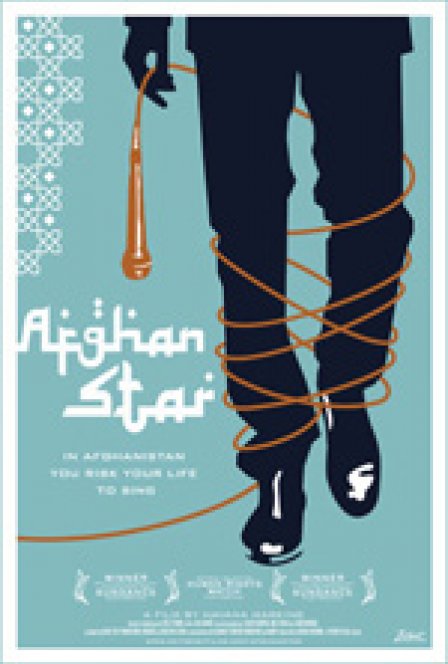

This is Afghanistan: Young, wounded, and hopeful. Under Taliban rule, singing was a crime. Last year, 11 million people -- one-third of the country’s population -- tuned into the season finale of Afghan Star, their version of American Idol. Havana Marking’s documentary, which follows the show from its early auditions to the final showdown, won the Director and Audience Awards at Sundance. And it’s easy to see why. The story has a sense of immediacy and an infectious optimism. However, the film’s macroscopic vantage keeps it from reaching any larger insight or mining greater emotional depths. The idea of singing as an act of defiance and hope remains compelling, but the film fails to move much beyond such platitudes.

At its best, the film uses the transcendent nature of pop to dissolve perceptions of Afghans as backwards tribesmen. “When we see the young generation of other countries,” says one interviewee. “We don’t see why we should be any less than them.” By the end of the film, we share the same view.

The mix of the alien with the familiar is often beautiful: Two women in burqas giggle at the sight of their favorite contestant; a young girl on her rooftop rigs a ramshackle antenna before joining her family around the TV. The text-message voting system that, to us, wreaks of 13-year-old girls is many Afghans’ first experience with democracy. Viewers tend to rally behind the contestant of their ethnicity, simultaneously reflecting strong ethnic divisions and hopes for national unity.

Just as compelling as the fans' experience is the story of Setara Hussainzada, a contestant whose small shuffle onstage incites disgust, derision, and death threats. She yearns for her family, but can’t leave Kabul without risking her life. Given the rosy nature of much of the film, Setara’s struggle offers insight into just how ingrained in the Afghan public conscience conservative Islam has become and how difficult the road ahead will be.

But beyond Setara, Afghan Star tends to break that sacred rule of narrative: Show, don’t tell. Much of the 88 minutes consists of Afghans telling us how difficult life has been, telling us how important music is today, telling us how dangerous it is just to sing. After the first few speeches, the wheels start to spin in the mud.

This obsession with the overarching significance of the show distracts the film from delving into its immediate subjects. We’re introduced to four finalists, each defined by an idol-style persona (the brazen frontrunner, the shy young 'un, the rebel) and a general position in Afghan culture, such as gender, ethnicity, or political bent. But we learn little of who they are off-stage — their past, their families, their ambitions. Instead, the film sees a false choice between depth and breadth, and chooses the latter.

Such superficiality also weakens the depiction of the television show itself. The program is portrayed as a selfless endeavor that arises with little effort, nudged on by looming conflict. That is likely because Kaboora Productions, which produces Afghan Star, also co-produced this documentary, undermining any claims of objectivity. As viewers, we can’t help feeling suspicious. Would you watch a documentary about American Idol produced by Simon Cowell?

Still, it’s hard to get upset at Marking, a British filmmaker, for being too polite towards her hosts. Shooting in Afghanistan is a feat in itself. Bathing in the film’s sense of hope is pleasant, and it’s affirming to see that happiness can bloom in the most desolate of lands.