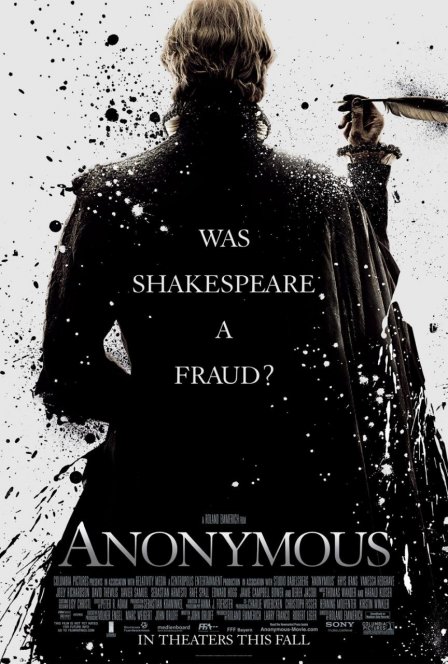

Appropriately, the film stock used in Anonymous looks like it was dipped into vats of the same prop ink strewn around the study of Edward de Vere (Rhys Ifans), the 17th Earl of Oxford and the man the movie posits as the actual author of Shakespeare’s 38 masterpieces. That is, Anonymous looks like what you would hope a historical fiction made by a CGI-loving super-director bent on debunking the “myth” that the world’s greatest writer actually wrote his own work should look like: sludgily dark, covered end to end with the griminess that romantics like to imagine made up the very air that was breathed in Elizabethan London.

Does that mean that director Roland Emmerich is now a romantic? It was the Romantics who first made it fashionable to restage Shakespeare all over the world and who elevated him to the godlike status he still maintains. But it was Emmerich who last made it fashionable to fantasize about destroying the world: as director of Independence Day, The Day After Tomorrow, and 2012, he’s the man responsible for the latest iteration of what film critic J. Hoberman has termed “the disaster cycle.” After the release of 2012 (in 2010), Emmerich commented that he didn’t think the public would follow him down the path of total planetary destruction one more time. So now he’s switched gears, and, wishing no longer to destroy our faith in the future of the world, he’s set his sights on our faith in one of history’s greatest artist.

In Emmerich’s oily view of Shakespeare’s London, Shakespeare himself was a hammy, drunken actor with a taste for plump whores — a bawdy type of man that the actual Shakespeare, the one who wrote all those amazing plays, would have gotten along with. Emmerich, however, following the lead of conspiracy theorist/screenwriter John Orloff, insists that such a lowly commoner would have been too busy drinking to be bothered with genius. So he offers de Vere, a wealthy London aristocrat of the period, as the real mind of brilliance.

Despite receiving credit for the invention of the human (to quote Harold Bloom), de Vere isn’t given much poetry to speak. The movie makes Ifans, as de Vere, hiss lines like, “My poetry is my soul!” It gives him speeches about the material of his plays rattling around in his brain, haunting and tormenting his every waking moment. “The only time I can stop the voices is when I put them down on paper,” he complains to his long-suffering wife, who only wishes he would put down the quill every now and again to attend to matters of business. Judging by his many shelves full of fat ledgers with titles like “Richard the Third” and “The Tragical History of Romeo and Juliet,” Emmerich’s de Vere shouldn’t have had many head-voices to deal with at all.

The secret playwright has a storied history with Queen Elizabeth the First, portrayed as a sexpot at 40 (by Joely Richardson) and a wrinkled piece of misspent youth at 80 (by Vanessa Redgrave). The question of her succession is of central importance to de Vere, mainly, it seems, for sentimental reasons. She believed in his genius when no one else would and supported him back when he was just a poor child prodigy. Later, he wrote (but shelved) many of his plays in order to get through to her, after their relationship was cut off by the evil Lord Cecil. When Cecil and his cronies plot to steal Elizabeth’s throne, it becomes up to de Vere to finally get his plays staged: he intuits that the right kind of political play may be able to incite a riot in the peanut gallery, the kind that could overthrow the plot against the Queen.

A pretty far-fetched plan, but if de Vere was blessed with the brilliance to write like Shakespeare, why not also with the clairvoyance to predict the actions of an angry mob? Using the lesser playwright Ben Jonson (Sebastian Armesto) as his pawn, de Vere funnels his work through to the Globe stage, under the name of the rakish actor who performs in them, and the world is exposed to great art.

It’s clear from even a cursory glance at the records that the Edward de Vere theory of Shakespearean authorship (formally known as the “Oxfordian” theory) is nutjob paranoiac fringework. On the one hand, it’s kind of insulting that a cabal of weirdoes (Emmerich and Orloff included) just can’t believe that a regular guy, an actor, could have penned such brilliance — for them, only a noble-birthed aristocrat will do. On the other, who cares who really wrote the plays, so long as they continue to be read and seen on stage? In the end, Shakespeare will live forever, whereas it’s much easier to imagine some futuristic peanut gallery still watching the streamlined spectacle of Independence Day, rather than the dense blackness of Anonymous, in 400 years.