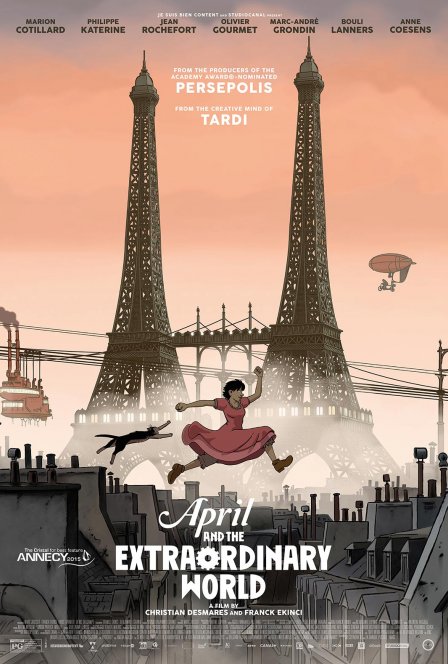

As a genre (or sub-genre), steampunk has always filled a unique niche. If cyberpunk became mainstream by predicting the world we now occupy, steampunk remains fixated on a past that never was. Steampunk’s entire premise relies on a kind of scientific what-if, which is exactly the origin story presented in the prologue sequence of Christian Desmares and Franck Ekinci’s April and the Extraordinary World, based on the graphic novel by Jacques Tardi. On the eve of the Franco-Prussian War, a scientific experiment gone awry kills Napoleon III. The incident averts the conflict, inciting a new historical timeline, but also sets science back in the crucial decades that lead to modernity’s breakthroughs. There are no World Wars, but there’s also no electricity. However, the science that did exist at the point of chronological divergence — steam power generated by coal, i.e. the “steam” in steampunk — devastates the world’s natural resources. Trees nearly become extinct due to the increased demand for charcoal, leading to an alternate conflict in 1941 between the still Napoleonic French Empire and the United States for control of Canada’s remaining forests. But all this is backstory for the film’s narrative.

April Franklin (voice of Marion Cotilard) is the great-granddaughter of the scientist whose experiment changed history. Separated from her parents at a young age, April and her talking cat Darwin (voice of Philippe Katerine) have survived on the streets of Paris while also trying to fulfill her family’s scientific legacy. The detail that explains all this is so richly interwoven into the film’s opening that it’s probably worth watching for that alone. After explaining so much in the prologue, the filmmakers feel satisfied to simply present their fictional world without stopping to justify any of it. So as not to ruin too much else, the rest of the story involves a family of dragons with advanced intelligence and the 20th century’s most important scientists. Again, this type of storytelling can be a little niche, but then again, what isn’t these days? Either that sounds great to you or you’re going to see Son of Saul for a bitter dose of historical realism (which isn’t to say a viewer can’t appreciate both).

There are few films that are equally as much love letters to science as they are to talking cats. In fact, in this world, the two are inseparable: Darwin the cat represents the potential for scientific achievement as well as a clearly referenced allusion to Perrault’s Puss n’ Boots. When Darwin isn’t lecturing April about geography or making wisecracks, he reverts to his feline nature by killing mice. Despite his forced evolution, he still retains traces of his animal instinct — and yes, he is named after Charles. Even the fantastic inventions in the film, the types of contraptions account for most of steampunk’s appeal, act as both visually compelling works of imaginative engineering, but also a reminder of our indebtedness to the actual scientific progress in our own time. The fantasy of science that never existed becomes an index for the importance of science in our time. The filmmakers acknowledge the destructive force that science can unleash, though the film ties it to the corrupting influence of power — Napoleonic or reptile overlord.

April and the Extraordinary World also subverts one of the more troubling tropes of its other genre: the treatment of female characters in animation. April is no princess: while she is born into a great scientific family, she earns her birthright through her own selfless efforts to restore science to its rightful place. She is also not a wide-eyed sex object; Tardi, the source illustrator who also serves as the film’s graphic designer, intentionally portray her as a realistic young woman. In fact, the real life Marion Cotillard looks more like a male fantasy version of a cartoon babe than the character she voices. There is a love story, but is almost tangential. The couple’s climactic kiss is almost literally tacked on to a scene conveying the importance of the other relationships in her life. The cat is the most powerful male figure in April’s life, functioning as a surrogate father, teacher, and friend. Fittingly, the film ends with a voyage to the moon. It’s a charming nod to Georges Méliès, but also manages to restore the historical and scientific timelines back to the period of the actual moon landing.