“If the Pirates of Caribbean breaks down, the pirates don’t eat the tourists.” —Ian Malcolm

Female Voice: Orange County Sheriff’s Office.

Male Voice: We need S.O. to respond for a dead person at SeaWorld. Uh… a whale has eaten one of the trainers.

Female Voice: [Pause] A whale ate one of the trainers?

Male Voice: That is correct.

This unsettling exchange appears in the opening moments of Blackfish, a scene I watched over a dozen times. I was hypnotized by the shock and confusion in the voices — how they sounded like they were being spoken underwater. But more important than the sound of the call was what the caller said: that the whale had “eaten” one of the trainers. The imagery it evoked was surreal: the stuff of summer blockbusters, not of real life.

The whale was Tilikum, a 12,000-pound orca, and the victim was Dawn Brancheau, a senior trainer with years of experience. On February 24, 2010, Tilikum grabbed Brancheau (either by her hair or her arm, a detail that remains a point of contention) and pulled her under the water, where she subsequently died. It was the third death involving Tilikum since 1991, and it renewed concerns over animal (especially marine) captivity, inspiring a book as well as this documentary. While Tilikum did swallow her arm, Brancheau wasn’t completely devoured or digested like the disturbing imagery of the call suggests. But the caller’s wording is startling and unnerving, evoking the same sense of awe and terror present at the park that day.

“The lack of humility before nature that’s being displayed here staggers me.” —Ian Malcolm

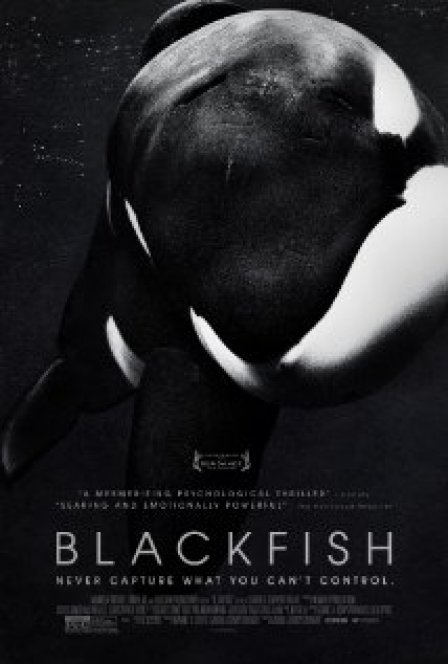

Blackfish traces the dark history of orcas in captivity, using the incidents involving Tilikum to provide narrative structure. By documenting Tilikum’s experiences and incidents at marine mammal parks around the world, Blackfish reveals the questionable operating practices and PR tactics used by these parks.

SeaWorld declined to be interviewed for the film, so the film’s interviews are limited primarily to former trainers and whale activists. The trainers show enthusiasm for their former jobs and compassion towards the orcas. But many of them started at SeaWorld very young, and with youth comes naivety. Now they are more concerned for the well-being of the captive animals they once worked with, and they regard SeaWorld with more than just a little suspicion.

But perhaps the most affecting interview in the film isn’t from one of the trainers; it’s from the grizzled old man with a full beard and arms covered in tattoos. He only appears once, but his bleak account of the capture of wild orcas is distressing enough to become memorable. “This is the worst thing that I’ve ever done,” he mourns. Indeed.

“Are these characters auto-erotica?” —Donald Gennaro

Tilikum was captured in 1983 in the North Atlantic, and has remained in captivity ever since, performing first at Sealand of the Pacific in British Columbia and later SeaWorld Orlando. At SeaLand, he was bullied by the more experienced whales and kept at night in a module only twenty feet across and thirty feet deep.

Following the death of Keltie Byrne in 1991, Sealand emptied its pools and sold Tilikum to SeaWorld Orlando, where he again spent long periods in isolation. The female orcas attacked him when he first arrived, and he was only put with them to breed. According to testimony in the film, one of the main reasons SeaWorld acquired Tilikum was to use him for breeding purposes. Despite his known history of aggression and a second, mysterious death in 1999, he has fathered over twenty calves since his arrival at SeaWorld.

“They should all be destroyed.” —Robert Muldoon

One of Blackfish’s achievements is its poignant and humane representation of orcas. Their strong family bonds, their elaborate emotional lives, and their complex language are all discussed. But even more effective than is the testimony from the former trainers — some of whom were involved in incidents with the whales — who continue to express an affinity with the whales, not fear. Blackfish repeatedly makes it clear that these animals, despite their intimidating name, are not murderous. Instead, it is the unnatural conditions of their captivity that drives them to psychosis.

“We’re gonna make a fortune with this place.” —Donald Gennaro

SeaWorld is a business, and in their PR practices they have perpetuated several different myths regarding the care and keeping of their orcas. They claim that one in four orcas has a floppy dorsal fin, when in reality the rate of occurrences in the wild is much less. Life expectancy in captivity is also less than in the wild, although SeaWorld claims otherwise.

Additionally, several incidents have been blamed on trainer error, including Brancheau’s death. Trainers interviewed for the film examine footage from non-fatal incidents, and conclude that trainer error is often not the cause. It’s in SeaWorld’s best interest to portray the animals as fun and friendly, not as beasts capable of aggression or violence. Numerous SeaWorld commercials and promotional videos are sprinkled throughout the film. Their cheeky and vibrant tone makes the shaky, handheld footage of the incidents all the more upsetting.

“What you call discovery, I call the rape of the natural world.”—Ian Malcolm

In its final scene, the Blackfish returns to the shock and awe of its opening moments, but with a different intention. The terror is replaced with wonder, the violence with beauty. There is a place where human and orca can meet, but it is not SeaWorld.