When economist Jim O’Neill coined the acronym “BRIC” for developing world economic powerhouses Brazil, Russia, India, and China, the sole South American entry in the group was on the cusp of a market renaissance. Through the 2000s, Brazil established the societal skeleton and sinew which allowed the country to boast large markets, the lowest unemployment rate in decades, and a political system ranked as “moderately free” in the Heritage Foundation’s Economic Freedom Index compared with the “mostly unfree” ranking of its peers. With all its promise, the first half of the 2010s saw Brazil ensconced in civil unrest, economic disparity, and a president on the verge of impeachment. The fantasy of a promising future gave way to the reality of an uncertain present complete with crumbling favelas and billions sunk on the 2016 Olympic Games. Some, however, are able to keep their eye on a brighter day.

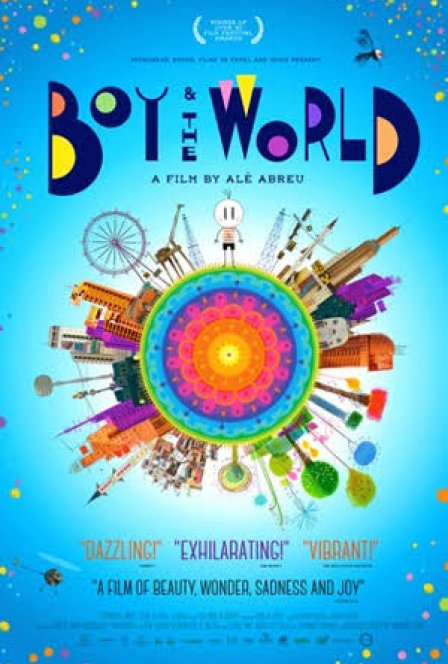

Director Alê Abreu’s Boy and the World is, like its home country, an amalgamation of a lot of great things. Following a young, nameless boy as he journeys from his agrarian farmland to the industrial heart of a city to find his father, the film makes an aural and visual odyssey through the past and future, rural and urban, rich and poor in a blur of color, pattern, and song. By pitting so many polarities against one another within an hour and twenty minutes nearly devoid of dialogue, Abreu succeeds in flexing Brazil’s cultural muscle, even if the story gets a little lost in translation along the way.

At its best, Boy and the World is an absolutely wonderful children’s film. The animation team’s ability to send the viewer headlong down a constantly shifting prism of texture and geometry is a filmic feat on par with the seminal animation of Richard Williams and his celebrated The Thief and the Cobbler. Glimpses of Abreu’s frenetic mind are clear and visible as the screen contracts to tightly-drawn linework and in the next moments bursts into a brushstroke world not far off from Nintendo 64 classic Yoshi’s Story. The film’s touted soundtrack of samba, hip-hop, and indigenous music floats along with the little sketched protagonist in a sensory melange that will fascinate adults and easily captivate any kid in front of the screen.

The problem lies in how long the magic can last. Without a rudimentary premise and no dialogue, Boy and the World is wholly reliant on visual spectacle to carry the story along. The film does a gangbusters job for the first half-hour, but the effect wanes the further along the film moves. The intent of an alternative storytelling mechanism is apparent and appreciated, but I couldn’t help but feel this would have worked best as a short, Abreu’s bread and butter. Questions of length aside, Boy and the World is a thrillingly impressive work from a director with the makings of a global animation powerhouse. The calls for Brazilian President Rousseff’s resignation and the inevitable PR firestorm of the 2016 Olympics will dominate news through 2016, but it’s good to know some are still looking to the future with a bright face.