At the age of eighteen, sculptress Camille Claudel came under the instruction of Auguste Rodin at the Académie Colarossi. Rodin partnered with her as a lover, teacher, and sculptor for several years, despite being married and fathering a child with his wife. The two artists engaged in a doomed relationship that Claudel eventually ended before having a nervous breakdown. She destroyed many of her own sculptures and lived in solitude until her family sought to have her committed. Her brother, the poet Paul Claudel, visited her throughout her stay at the Asile de Montdevergues, where she would continue living for thirty years until her death in 1943. Although various psychiatrists and nurses advocated for her release from the institution, her brother and her mother never allowed it. Buried in a communal grave, her body will never be found.

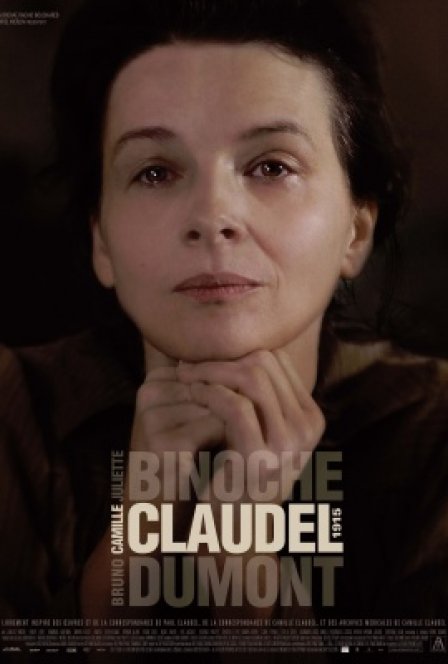

Claudel’s story seems made for a Bruno Dumont film. From Twentynine Palms to this year’s incredible Hors Satan (TMT Review), Dumont’s men and women navigate each other’s physicality with a desperation bordering on annihilation. Camille’s relationship with Rodin was so intense, so invasive, that it supposedly drove her to insanity. And Dumont is at his best when navigating the mania that takes us from standing at a clearing and admiring the sky to foaming at the mouth while being fucked by a stranger in the woods. But Dumont’s newest film, Camille Claudel 1915, is not the story of the artist’s relationship with Rodin, but rather her confinement within the Asile de Montdevergues. Dumont eschews the melodrama of romance (see Bruno Nuytten’s 1989 film, Camille Claudel, for all the melodrama you can handle), and instead focuses on the days during which Camille (Juliette Binoche) prepares for a visit by her brother (Jean-Luc Vincent). Working from letters and medical records, Dumont pieces together a life of genius, inspiration, depression, and betrayal, and condenses it into a three-day portrait of asylum living.

Regarding the decision to work with real hospital patients, Dumont has said in press materials, “It is necessary to have precise spaces into which the unexpected can occur.” By turning the camera on non-actors and actual nursing staff, and requesting that everyone refer to Binoche as “Camille” throughout the shooting, Dumont’s orchestrated restraint allows for the film’s most incredible moments. In order to create a safe space for patients to explore the dynamics between themselves and a woman ‘playing’ with them, the shooting process became a rigorous exercise in the unexpected: “But it will be Christiane, Myriam, Jessica, contemporary mental patients, who are saying something ancient, still valid today, about which there isn’t much comment to make. There is nothing to say. I never know what’s going to happen, and that’s exactly what interests me.” The film certainly belongs to Binoche, as she carries the weight of a woman’s doomed existence in her face, sculpted by age and severe beauty, but Camille Claudel 1915 is most affecting when left to the patients. The women smile, drool, bang their spoons against the dinner table, laugh, touch one another with a kind of delicate hesitancy that comes from being told not to touch. It’s fascinating to watch Binoche improvise with them, her eyes focusing and adjusting to whatever they do next. Mental illness is absolutely a mirror, a glimpse at what it’s like to live inside a wall. Most of us are already there, and this recognition can be a terrifying surrendering. As one woman stares at a tree in the courtyard, her face contorts into a wide-mouthed, high-pitched whine turning into laughter. Most of her teeth are missing and the ones left inside are rotting. Dumont’s camera lingers. A moment like this is alive. Any audience regarding Dumont’s decision to cast real patients as ‘exploitative’ is probably the same audience who nominated Leonardo DiCaprio’s performance as Arnie Grape for an Oscar.

The first half of the film creates a space that wraps around itself in such simple action: Camille cooks potatoes; she prays; she sits in the sun-room and notices the light; she walks; she picks up mud and tries to sculpt something with trembling hands; she sits. Many of the minutes feel like being chain-fed Ativan, a dozing off to a vague awareness of existence. It is post-boredom. What ruins this nothingness is the arrival of Camille’s brother, Paul, and the latter half of the film’s shift. He has a few lengthy monologues on Christianity, his belief in God, and his sister’s condition, and when he finally arrives at the asylum, the interaction is so brief and one-sided (Camille basically begs for her release), that one wonders why it’s even there at all. Why ruin a mood that’s already gone fluid, by introducing speech and a formulaic interaction? Dumont has never been the kind of filmmaker who sets out to ‘tell a story’ (thank god), instead opting for visuals and moments that go on forever like we’re in the memory of another movie. He didn’t go to film school, and his earliest films were industrial documentaries depicting “the insides of tractors… notaries… ham…” To watch the second half of Camille Claudel 1915 bomb so completely with an unnecessary shift in tone is annoying — mostly because self-reflection is always less interesting than the immersion of moment to moment — and it feels like a bogus move on the director’s behalf. The deeper we’re allowed to go into the dark maze of Camille’s everyday, the more the terror comes on. Too bad Dumont turned it off.