Czech author Arnošt Lustig, upon whose autobiographical novel A Girl from Antwerp this film is based, holds a special place in the history of twentieth century Czech literature. A survivor of three separate concentration camps who escaped from a train bound to a fourth (Dachau) after an American fighter-plane blew up its engine, Lustig immediately returned to his native Prague to help fight in the 1945 uprising against the Nazis in the ancient city. Drawing upon some pretty harrowing lived experiences, his writing is as devastating as it is beautiful, and it’s not surprising that several of his fellow Czechs have made films from his body of work. A Girl from Antwerp is particularly cinematic, as it’s essentially a boy-meets-girl love story set against the backdrop of one of the most absurdly violent locales imaginable, namely, Auschwitz-Birkenau.

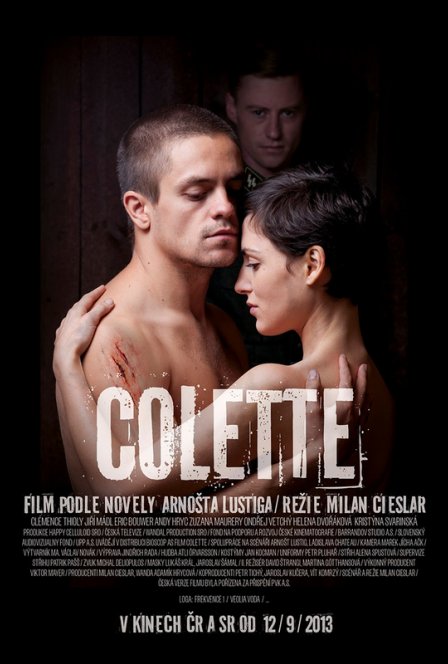

Vili (Jirí Mádl), Lustig’s fictional self in the film, is a runner at Auschwitz. He spends long, depressing hours transporting as quickly as he can the clothing of recently arrived prisoners to a sorting building where Colette (Clémence Thioly) spends her equally depressing days meticulously poring over all sorts of personal effects, looking for hidden money and valuables which will be used to fund the German war effort. The filmmakers quickly establish how futile and urgent these two young Jews must feel every action is, allowing this desperation to seep into the very fabric of the film. In between inhuman punishments and the constant fear of completely irrational shootings on the part of the camp guards, the two of them somehow form a connection, which, while very convincingly portrayed by Mádl and Thioly, still suffers from some unintended clichés of both the romance and war film genres. A narrative that jumps back and forth from 1978 in NYC to 1945 in Auschwitz doesn’t help much, either, as it comes off as more of a tacked-on bookend to the film than anything else.

With such heavy and culturally familiar source material, it’s only natural to question why Milan Cieslar would decide to go ahead and make another movie about Auschwitz. The movie is filled with tropes we’re all familiar with, and while they’re still no less resonant a lesson in the banality of evil and humankind’s propensity to be absolute beasts to one another, the opportunities for cinematic originality and insight in this brutal milieu seem to have been mined for all they’re worth. What really establishes Colette as a notable entry in the Holocaust genre is the brilliant and downright painful work of actress Clémence Thioly in the title role. She’s in love with Vili, but caught in an awful situation with a higher-up German official at the camp which finds her trading supremely unnerving sex in exchange for her life. Largely unknown outside the circle of people who are really into MOR French television, Thioly’s face is impossibly expressive. Cieslar knows this, and spends just as much time as he needs to allowing her nuanced expressions to impart an incredible amount of gravity to her scenes.

The unavoidable reality is that Colette is a familiar story about life in concentration camps that probably won’t pique the interest of very many Western moviegoers. We’ve seen this story play out in myriad television mini series, feature films, and documentaries. Colette isn’t really breaking any new ground, and it feels a little weird owning up to the fact that a lot of people aren’t going to be exactly thrilled by another film about the Holocaust, since it’s still one of the most singularly dire things that’s ever happened. Regardless, some incredibly strong performances and a generally inventive visual style save this film from drowning in the current of countless other, generally not great movies about WWII in general and the Holocaust in particular.