Last year, movie theaters began the switchover from analog to digital projection as major film stock manufacturers ceased production and studios announced their intention to stop screening 35mm prints altogether in most of the developed world. Yet despite being the only artform named for the raw material of its production (imagine “sculpture” renamed “stone”), the death of film has so far been a feature without much drama. Independent cinematheques upped their fundraising efforts, scrambling for money for digital projectors that can accommodate new film releases, restorations of old films (which will no longer be released on film), and the increased costs of renting actual, archival film reels (now irreplaceable and thus more valuable). A few of the world’s greatest directors made notable, or imagined, statements on the subject. Leos Carax created a film that might be a metaphor for the end of film-based film, and Béla Tarr made a film about the apocalypse — literally ending with the lights going out — that probably wasn’t (but that I interpreted as such, anyway) and then retired. More recently, Pedro Almodóvar jumped aboard the digital filmmaking 747 without making a big conceptual fuss over it, but in the process made one of the worst films of his career.

While the digital projection switchover will cut costs for multiplex chains and studios, its clinically-precise picture holds no real benefits for filmgoers or makers (or the numerous independent theaters it might force out of business). On the other side of the lens, though, digital cameras have been opening up radical new possibilities for directors looking to do more than just cheaply and conveniently mimic the aesthetics of traditional film. For every wrongheaded embrace of tech for tech’s sake like The Hobbit’s pointlessly sped-up frame rate, there have been handfuls of directors attempting to use technology less prosaically. This year’s Leviathan, for instance, employed a dozen miniscule, waterproof GoPro cameras mounted throughout a deep sea fishing boat to document the mining of ocean life with a combination of intimacy (one camera floats back and forth in a bloody bin of fish guts) and detachment (what the cameras capture is mostly up to chance).

But it’s not just innovative devices, or even expensive ones, that have inspired innovative filmmaking. Recent movies from David Lynch (Inland Empire) and Jean Luc Godard (Film Socialisme) have used — wholly or in part — camera phones to explore the aesthetics of digital distortion. Consumer technology became a tool of resistance — real and symbolic — for Iranian director Jafar Panahi, who shot This is Not a Film with an (this is not a film camera) iPhone and had it smuggled out of the country on a thumb drive. And Zachary Oberzan, for his debut film Flooding with Love for the Kid, used a shitty webcam to transform his 90-square-foot apartment into the vast, bloodsoaked landscape of First Blood with an aesthetic unity (YouTube stunt turned epic) and celebratory playfulness that would have been impossible to achieve with more professional equipment.

Nonetheless, filmic digital experimentation has for the most part limited its scope of inquiry to our contemporary, pixel-drenched world, rarely turning its cheap, plastic lens to analogue precedents. Sure, there are notable exceptions, like Everything is Terrible’s trashcendent computer-assisted assemblages of VHS discards, but overwhelmingly, when digital filmmaking regards itself, it’s always like a teenager: fantasizing about its endless future, fussing about how its skin looks today, but never reflecting on its lineage or relationship to the past. It’s as if the break between cameras with reels and those with hard drives — and the cultures they each capture — were as cleanly defined as the luminous, CGI lines in Tron.

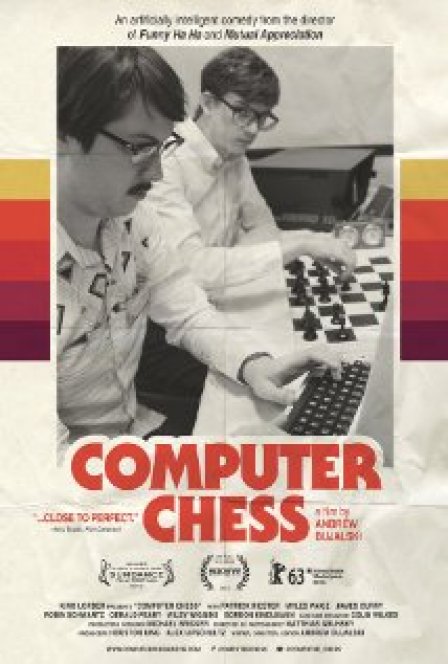

It seems significant, then, that one of the most fascinating commentaries so far on the digital and its relationship with the analogue is a film that nearly refuses to distinguish between the two at all. While singlehandedly constructing a complex, and at times anarchic, network of bridges across the conceptual canyon that has so far divided digital and analogue cinema, Computer Chess, the fourth film from director Andrew Bujalski, also extends its deconstruction of dichotomies well beyond the subject of film itself. Computer and human, order and chaos, historic specificity and abstracted universality, meaning and noise, lots of cats and no cats — these are just a few of the false pairs that the director hilariously, charmingly, and inventively obliterates during the film’s 90 minutes.

Computer Chess is a period piece that’s set in an era dominated by 35mm, but it’s shot with digital cameras; it’s from a director whose previous work has all been set in the present-day, but shot on grainy, nostalgia-inducing 16mm film stock. Yet the photographic apparatus’s relationship with its subjects is no simple inversion of the director’s — and film in general’s — usual formula: Computer Chess was shot on AVC-3260 video cameras (developed in the late 1960s), which use tubes (can’t get more analog than that) to convert black and white images into a digital signal. If the technology of the film’s production suggests a more complex relationship between digital and analog than we’re accustomed to, its narrative is nearly Gordian in its treatment of our relationship with technological progress. Bujalski not only used these era-appropriate cameras to create the film; they also appear within it: in an early scene, a member of a film crew there to document a chess tournament chides a cameraman for shooting at the sun, which can damage the tubes. When we see the footage, the sun distorts into a black circle as it fries the camera. The boxy size and blurry black and white of the AVC-3260’s images are ideal for evoking found public access documentary footage, but Computer Chess quickly abandons the mockumentary pretense — or any singular perspective — as it blends narrative and editing techniques like its cameras do formats, chipping away at what would otherwise be a formidably unified 1980s aesthetic. Sound and image disconnect, a brief sequence is in color, and a hallway fills up randomly with cats. Digital and analog together make an image; the concrete and the abstract together make a thought.

Set in the early 1980s — when computing was still a Wild West of technical non-standardization populated by programmers whose cultural landscape was just as undefined — Compter Chess takes place nearly entirely inside a nondescript hotel during an annual convention where, over the course of several days, teams of programmers from MIT, CalTech, and some other unnamed organizations pit their proprietary chess programs against each other. Like the droids in Star Wars (versus the assembly-line similitude of humanoid drones in sci-fi films released post-PC/Mac duopoly), the computers from each team are as physically diverse as their programs: the device used by the team that the film’s sorta-protagonist Peter Bishton (Patrick Riester, in one of film’s most convincing portrayals of passively pent-up nerdom) is on takes two people to wheel down a hallway, while the computer used by an overfunded programmer working for an unnamed organization with ties to the federal government looks more like an oversized answering machine whose only display is the reel of paper it prints its next move on.

By setting the film at such an early stage in the development of computing, when the field was still amorphous, Bujalski sidesteps cinema’s usual technological-determinist approach to computing and artificial intelligence; instead of adolescent fantasizing (science fiction) or old fogie get-off-my-lawn-kids-ing (The Social Network) about what technology can do for — or to — humans, Computer Chess’s approach to tech is both anthropological and phenomenological, positioning computers as part of a wider system of human social interaction and philosophical inquiry. Computer Chess has, deservedly, been nearly universally praised for the visual verisimilitude of its 1980s mise-en-scene, but just as stunning is how accurately it captures this combination of solitude and detached socialization that defines most academic conferences for their participants. Accordingly, though it’s ostensibly about a chess competition played by computers, the hilarious motherboard of the film is found wandering through drab hotel hallways, downing Scotches to lube up conversation in bars, trying to find a place to sleep after being locked out of its room, not-quite flirting with the convention’s lone woman, Shelly (Robin Schwartz), and engaging in debates with middle-aged swingers about abstractions like order and randomness. What technology wins chess competition is, ultimately, inconsequential, but the formal structure of the tournament and rigid grid of the chessboard do guide the participants as they assign the fuzziness of meaning to their experiences, even those created by their interaction with machines.

A little over ten years ago, Andrew Bujalski released one of cinema’s most mild-mannered game changers, a low-budget film about post-college indirection whose elegantly rough-hewn aesthetic, naturalistic um dialogue, and deceptively modest scope inspired a generation of D.I.Y. filmmakers. That masterful debut, Funny Ha Ha, also spawned one of contemporary cinema’s most unshakable, and inaccurate, generic descriptors: “mumblecore” — a label that, in many circles, has acquired most of the negative connotation and all of the overly-broad application as the term “hipster.” While originally coined in reference to the shitty quality of the recorded sound in Funny Ha Ha, as a derisive descriptor it became applied to any film in which the twenty-something characters spoke with the pauses, ums, and likes of everyday life’s unrehearsed dialogue. But Computer Chess’s carefully-crafted fusing of order and chaos make clear what Bujalski’s admirers might have already suspected: instead of stylistic signifiers of slackerdom, these lapses in articulateness reflect a deep interest in the spaces between meaning and meaninglessness. Computer Chess improbably manages to fully occupy that ever-shifting place.