It’s a sin — something akin to performing a C-section with a medieval dagger — to plod methodically through battle scenes in a film that promises, and delivers, nothing more. Conan the Barbarian, with just such a C-section and just such a set of battles, is sinful. But within a certain mindset — where you went in with higher hopes but quickly learned to expect nothing more than torture-porn for the Lord of the Rings set — it commits only minor ones, not murdering its brothers so much as coveting its neighbor’s wife.

Conan opens with a nice double-whammy of disgusting fun. In the first, it manages to covet The Fellowship of the Ring, War of the Worlds (Spielberg’s version), and March of the Penguins all in one go. In rapid time, we’re run through a Morgan Freeman’d monologue of hokum about ancient myths and mysterious rituals, accompanied by a montage of wizards and tribesmen forging mystical weapons. Freeman’s on autopilot and so is the pseudo-mythology, but it goes by quickly, slamming us with wild and fiery exposition. The lesson is clear: not “set up your mythology well,” but “ race ‘em through the exposition with a lot of color and big words, and get on with it.”

So, just as quickly, Freeman’s voice drops out. We enter on a barbarian battle scene. The Viking-like Cimmerians, from which tribe Conan hails, fight a gruesome battle against an indistinguishable enemy. In the midst of it, a knotty-haired pregnant lady (battling nonetheless) is run through nearly to death. Her husband (Ron Perlman), at her solemn request, carves their screaming son from her womb and holds him up to the sky. Tight on the bloody newborn, smoky battle-sky fills the background, war cries booming… title card: Conan The Barbarian. So far, only the good sins.

The movie dwells on relative virtues for a bit. Conan’s childhood under Perlman’s fight-tutelage… his trial-by-fire, when the invading Khalar Zym (Avatar’s Stephen Lang) comes crashing in on the Cimmerians, seeking the magical hokum Morgan Freeman told us about. Perlman is viciously killed by Zym, whose zeal for nastiness is likely the root of Conan’s later predilection for inventive sadism. Then it’s back to degradation: we smash into Conan’s adulthood, where he’s become a long-haired beefcake who carouses with whores and tortures his victims (one fat man loses his nose to Conan’s sword and later endures The Barbarian’s finger deep in the cavity thus left) about as much as he quests for revenge against Zym.

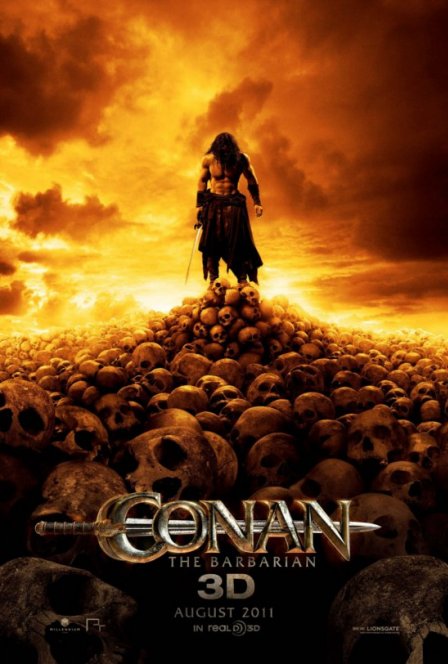

It’s not long after meeting adult Conan when we realize the movie climaxed somewhere around the bloody newborn. Once this sinks in, it’s best to sit back and try to enjoy a carnivore’s diet of sword battle after sword battle. But the creative violence, the only thing the movie has done well, produces continually diminishing returns. By the end, we’re watching a CGI-melee of loose plot points unraveling, and the movie has lost even the courage to be depraved.

The only other 2011 movie along Conan’s lines was the defiantly above-average Channing Tatum vehicle The Eagle, wherein the analogy to W. and Iraq II would have been palpable had it not been stomped on by a movie pretending to be oblivious to them. But at least The Eagle tried to make itself relevant. Conan is one of those movies that piles on the gore in hopes that its R-rating will deliver enough mutilation and steel-edged mayhem to compensate for the teenagers it lost when it upgraded from PG-13. When you don’t even make the effort to seem relevant, there’s nothing to do but spiral downward — scene after bloody scene begin to blend together until the boredom is as terminal for the audience as Conan is to his enemies.