Here’s a familiar figure in American cinema: a soldier who comes home to a life that offers no relief from the violence and disorientation of war. This character was a staple of 1940s noir, and three decades later he became a symbol for the anxieties of a nation embroiled in Vietnam. Over the past several years, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have inspired a spate of undistinguished independent films about scarred veterans struggling with readjustment. The latest of these is Cost of a Soul, a painfully overwrought drama set on the mean streets of north Philadelphia.

In the film’s prologue, Tommy (Chris Kerson, who resembles a cross between James Franco and James Woods) and DD (Will Blagrove) return in uniform to their old neighborhoods, while Tommy experiences a confusing war flashback. The opening scenes are shot in black and white, with heavy-handed color splashes (a cigarette coal, blood, a girl’s irises); afterwards, the palette switches to full, if washed-out, color. The dual leads’ military service is rarely addressed again as the film settles into a conventional but convoluted crime story. Tommy, in an effort to support his bitter wife and the daughter who was born in his absence, resumes the racketeer’s life he’d thought he could escape by enlisting. Meanwhile, DD strives in vain to keep his two brothers out of trouble. An assortment of ruthless but pathetic thugs and corrupt cops scrabble over what appears to be the mysterious briefcase from Pulp Fiction. (When it is opened, the interior glows, but the audience never sees what’s inside.) The fates of Tommy and DD converge in a manner both predictable and encumbered with leaden irony.

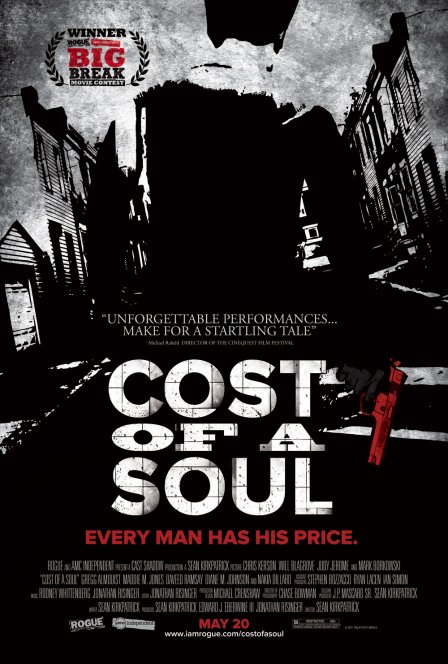

First-time writer/director Sean Kirkpatrick shot Cost of Soul with money he raised himself, then entered and won the Big Break Movie Contest sponsored by AMC Theaters and Relativity Media’s Rogue Pictures division. The prize was national distribution and marketing. I wish I could say this encouraging success story has culminated in the wide release of an exceptional or even noteworthy movie, but Kirkpatrick displays little skill as a filmmaker. He deals with inner-city crime in the most on-the-nose fashion imaginable. The performances of his actors are all knitted brows and clenched jaws as they recite cringeworthy dialogue that sounds like a foulmouthed version of an After School Special. Kirkpatrick shoots much of the film’s abundant violence in tight closeup with a lurching handheld camera; it’s difficult not to get seasick, much less make sense of the action. (As if that weren’t enough, flash cuts are added to the mess.) He does make good use of his locations — the decrepit rowhouses and garbage-strewn lots say more about urban blight than his words ever could — but any hint of local flavor is obliterated by the inability of any of the cast members to perform a credible Philadelphia accent. This is yet another Philly-set movie where all the characters sound as if they’re from Brooklyn.

About the only thing Cost of a Soul has going for it is its heart, which is in the right place. Kirkpatrick doesn’t glamorize urban violence but portrays it as a grim cycle, and he offers no false hope. His intentions are unquestionably good. But good intentions have never guaranteed good art.