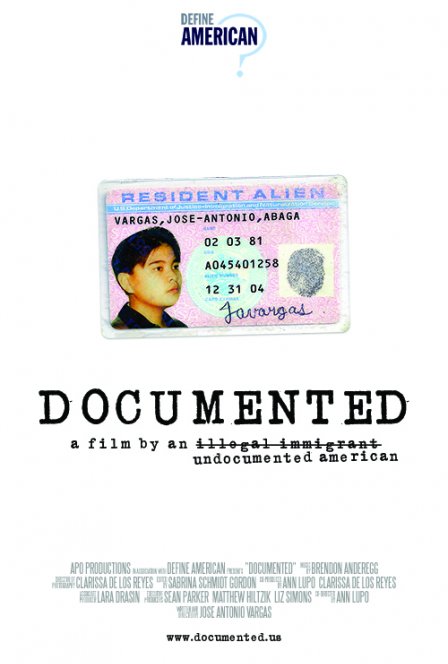

Anyone a witness to the immigration “conversation” in today’s major media platforms can attest to the egregious fashion in which the “illegal alien” and the “real” American are dichotomized, then bandied about (in a feedback loop of ignorance ranging from YouTube comments to Tea Party graphic tees). Documented is the saga of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas and his identity as an undocumented immigrant. By revealing himself as an undocumented citizen, Vargas emboldens the greater population (approximately 11 million) of undocumented people within the US and the complexities through which they must navigate.

In 1993 (at the age of 12), Vargas arrived in the United States from the Philippines without the necessary documentation towards citizenship. His migration was through the volition of his grandparents, who wished to accord him greater opportunities (via a marriage to an American woman). His unanticipated separation from his mother (who remained in the Philippines) was indelibly traumatic, and an example of the the psychological implications of draconian laws surrounding immigration and visitation. While coming of age, Vargas was straddled in cultural limbo. During his high school years, he acknowledged himself as gay, which was later complicated by his discovery of his “undocumentation” during the requisite trip the DMV at the age of 16.

In adulthood, Vargas experienced increasing success and visibility via his journalistic career, and then became burdened in proportion by the reality of his “undocumentation;” this is how Documented transpired. Vargas chronicles his intent to publicize and proliferate his own story, addressing audiences ranging from a classroom at his own high school in Mountain View, CA, to the neoconservative attendees of a Mitt Romney, to a roomful of young adults also living under the undocumented stigma.

Documented is in advocacy of DREAMers; those who would benefit from the DREAM (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act. Vargas exposes what is disturbingly present in the lives of undocumented citizens, which includes the unsettling, if not practically Darwinistic notion of “earning” your way to American citizenship; an elderly couple assure Vargas that he is “deserving” of citizenship, solely on account of his journalistic achievements, repeatedly suggest that he contact their local senator about his “credentials” (as if they were recommending a local dentist). Equally disturbing is a recurring idea of what constitutes a “worthy” American, which surfaces intermittently throughout Vargas’s interviews. In the perception of citizenship as defined by an inherent “worth” of a human, one hears echoes of horrific traditions of repression and racial superiority.

In Documented , Vargas uses his own experience to explore the emotional gravity surrounding issues of identity, lack thereof, and the consequent repercussions on family and relationships. His separation from his mother took place 20 years prior to the making of the film; Vargas wants to embrace her repeated attempts at re-establishing contact with him, but is actually so distraught by the growing rift of separation and abandonment that it proves to be more challenging than anticipated.

Vargas, as a narrator, occasionally succumbs to long-winded anecdotes in an almost theatrical fashion; however, this is only natural in that he’s coming from an extremely vulnerable space. As the firstborn child of immigrants, this film resonated with me, and almost painfully so, as I pieced together small fragments of his experience to those of my parents. While my family’s circumstances were not identical to Vargas’s, we occupied adjacent spaces. Vargas breaks his silence with his mother at the end of the film, in the form of a tearful Skype conversation (he is unable to visit because of his status). Including this in the documentary isn’t narcissistic or emotionally designed; this is something that actually happens to people, and therein lies the sociopolitical importance of narratives like Documented.