Cinematically speaking, small-town America has yet to recover from David Lynch. When Blue Velvet shredded the veil of exurban morality in 1986, it was a revolutionary idea. Now, like all great breakthroughs, the idea that the wholesome exterior of Americana conceals a dark and deadly secret has become the status quo. If a family seems happy, they are not, perhaps because the father is a former mob hitman, as in David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence; maybe the father is having his wife kidnapped for ransom from his in-laws, as in the Coen Brothers’ Fargo, or just pay to have her offed altogether, as in their Blood Simple.

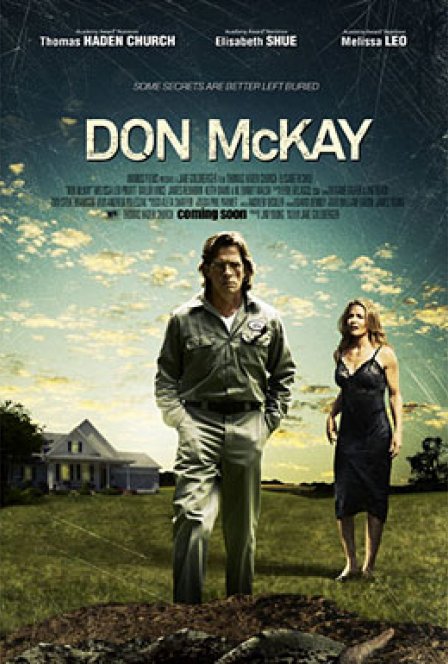

Writer-director Jake Goldberger directly cites this latter film as the inspiration for his debut feature Don McKay. The eponymous hero (Thomas Haden Church) slowly trudges through life as a high school janitor. As we watch him cleaning red paint off the floor of an art room, there’s a hint he may have to do the same with blood in the not-too-distant future (he does). After receiving a letter from his high school sweetheart Sonny (Elisabeth Shue), he returns to the town he abandoned 25 years ago. Sonny is dying and claims to have had a change of heart about Don after all this time. But something is not quite right about the situation: Is it Sonny’s omnipresent nurse Marie (Melissa Leo)? Or her groping physician, Dr. Lance Pryce (James Rebhorn)? Or the photos of her in the house (every one of which seem to have been cropped)? After a few twists and turns, no one, not even a simpleton like Don, is what he or she seems.

As a cautionary tale about the dangerous intersection of deception and self-interest, the film works on a certain basic level. There is an element of pleasure in watching people continually do the wrong thing, and Goldberger clearly gets that. He even manages to throw in some nice off-kilter touches, such as the shot of a purportedly “haunted” jukebox coming to life in an otherwise empty home. But the real specter here is that of Joel and Ethan Coen. The Coens made their name by creating a unique voice, so why does Goldberger continually succumb to simple imitation? Even when Goldberger is most successful at drawing out moments of awkwardness and dark comedy from his cast of dimwitted solipsists, it simply plays as “Coens lite.”

Moreover, if the film is intended to explore the psyche of its title character, it does little to show how life in this small town shaped Don into the pathetic and lonely soul we see. Rarely do we get a sense of how such an insulated environment managed to transpose itself onto one of its denizens, but that seems to be the assumption Goldberger makes about his protagonist. Perhaps Goldberger feared giving away his twist ending, but that ending, like most of the rest of the film, does not really offer any insight into the world he creates.