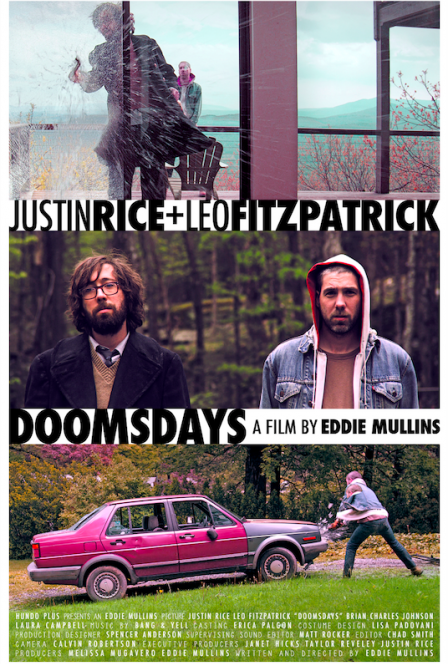

Why are we all in such a rush to get to the end times? Looking around the media landscape, there are many series in print, film, and television dedicated to either a dystopian future or some apocalyptic scenario where society as we know it has broken down. All of them show the post-judgment day era as a less-than-good time, but are we all secretly hoping that they come to pass? Maybe we can only understand modernity when we know there’s a period at the end of the sentence, like viewing a TV series through the prism of its finale or a film’s success based on its third act. But for all of the fantasy, and for every doomsday-prepper out there, how many would actually relish the time when things fall apart — at least subconsciously. In Eddie Mullins’s feature debut, Doomsdays, a pair of hipster buddies embrace the looming apocalypse (whenever it may actually hit) and use it to justify a life of preparing for the worst. The resulting film is an amusing diversion that has some darker elements to it, but never goes much below the surface.

Dirty Fred (Justin Rice) and Bruho (Leo Fitzpatrick) become scavengers and drifters in the Catskills, living off the largesse and incompetence of many a summer rental house to stock up on food, shelter, and lots of booze. Dirty Fred seems like a gentleman hobo, festooned in his overcoat, vest, and shirt with a tie, as he seemingly drifts through the life of breaking and entering while also pursuing the closest bottle of scotch and easily conned woman to bed. Bruho, however, seems more engaged by the mission; the one actually and actively preparing for the end times that peak oil will bring when petroleum can no longer be used in nearly every mass-produced product. To use a metaphor from the film, both believe they are on the Titanic, but one is crafting his own lifeboat while the other is merely raiding the ship’s bar’s top shelf. Now that they’ve been doing this for a while, what happens when they meet others along their journey? Particularly when two other outsiders, Jaidon (Brian Charles Johnson) and Reyna (Laura Campbell), seem enchanted by this meandering lifestyle?

Doomsdays is not a bad film, and it’s not a great film (though I’m of the firm belief that every film could be someone’s favorite), either: it’s perfectly adequate. The jokes and witty banter land well, and the performers all shine in their parts to deliver entertaining characters. Johnson and Rice in particular get the lion’s shares of bon mot comic moments, and acquit themselves well. It’s shot competently on RED cameras, with the beautiful outdoors setting almost always in some part of the frame, as if to suggest a return to nature is always a possibility for escape. The score is not the usual plaintive guitar picking of the indie film scene, but a jaunty little ditty that suggests Wes Anderson’s work with Mark Mothersbaugh. And yet, there’s not much depth to any of it.

Fred is a selfish bastard who is using Bruho’s mania as a reason to check out of society and indulge in his own whims. Bruho is the maniac who attacks cars because of the waste they represent and the folly that will inevitably (to him) lead to man’s downfall. But there’s never much more to it than that. And perhaps that’s okay; Mullins has created a unique and interesting entry point for these characters, but beyond that initial concept the film feels a tad like a hangout movie that wants to be more than it is. Doomsdays is the type of film where, if a friend told me he saw it, I would say “Oh I saw that, it’s decent.” then probably would quote a line I thought was funny from it before moving on to another topic.

The end of the world fascinates us because we don’t know what we would be without certain things in our lives. Strip us of our ephemeral possessions, our jobs, and our daily routines, and what would we find underneath it all? Would we just become free-floating hedonists? Would we develop attachments to new things? Would the old petty problems of jealousy and resentment remain even as the former world to which they belonged slips away? Doomsdays asks these questions, but always with a shrug and a wink, and never really answers any of them. It’s the end of the world as we know it, and the film seems just fine with that.