It’s not every day that you get to watch a film directed by someone who’s over a hundred years old. Born in 1908, Manoel de Oliveira has been directing films since 1931, and it’s safe to say he’s learned quite a bit about his craft in the past seven decades. Perhaps it is this very experience of Oliveira’s that renders his latest work completely stale and nearly lifeless. Charles Bukowski once wrote, “as the spirit wanes / the form appears.” I strongly believe there’s neither a better nor more apropos notable-quotable to describe Eccentricities of a Blond-Hair Girl than that. The film is an intricate and painstakingly formal drama, wherein every foreshadowed event comes to pass in a perfectly logical manner. Based upon a short story by Portugal’s most famous naturalistic author, Eça de Quierós, Eccentricities relates the story of a young businessman and his tragic fate.

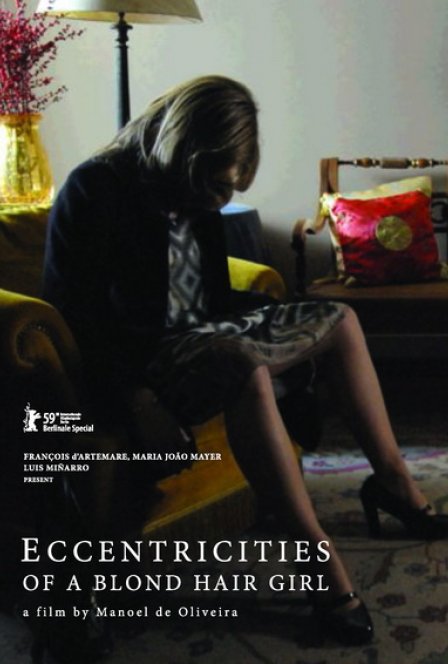

Working as an accountant in his uncle’s clothing store, Macário (Ricardo Trépa) becomes completely infatuated with a young bond girl who keeps fanning herself at the window in the apartment across from his office. The girl in question, played consummately well by Catarina Wallenstein, is as perfectly boring as she is attractive. She lives with her mother, which — natch — proves to be an obstacle for Macário, who becomes increasingly obsessed with her each day. The story itself is well-worn, and there are no surprises whatsoever in the tedious and apparently important goings-on that take place between his first glimpsing her and winning her over.

It’s not that Eccentricities is a bad film — it’s actually quite perfect — and that’s the trouble. It’s like watching a really well-made instructional video about something you’ll never be interested in. Yeah, the lighting is cool, and the acting is measured, and the story resolves itself very neatly by the end. But what’s the point? There is nothing in this film that manages to set it apart from even the most rote Mobil Masterpiece Theatre period piece. Oliveira has stated that he makes movies for the sheer pleasure of it, that he could care less about what critics think. At his age, who could blame him? However, one marvels at why he would spend so much time and effort at this point in his life on something so uninspir(ing)/(ed).

One might actually see this as the antithesis to last year’s Limits of Control. Whereas Jim Jarmusch played with various elements of form and ultimately transcended them, Oliveira seems mired in the technical “right” way to make a movie. Hopefully he had fun making it, and lord knows the old man’s paid his dues. It’s just horribly frustrating to see him make something this boring and by-the-numbers in the twilight of his career.