At this point, every summer tentpole film seems like a state of the union address about the summer tentpole film. The Amazing Spider-Man 2 is about little more whether Sony can get the American public to care about a franchise reboot that came far too quickly. (Verdict: delayed.) Captain America: The Winter Soldier asks whether an unexpectedly fun origin story, made because of the dictates of the “Marvel Cinematic Universe,” can be transformed into a durable series on its own. (Verdict: ye$!) Godzilla seems to openly wonder how successful a film can be when it spends half of its running time with human beings it clearly doesn’t give a shit about. (Verdict: pretty!) These meta-commentaries are prominent enough in the public imagination that they parasitically inscribe themselves on the viewer’s evaluation of the final product.

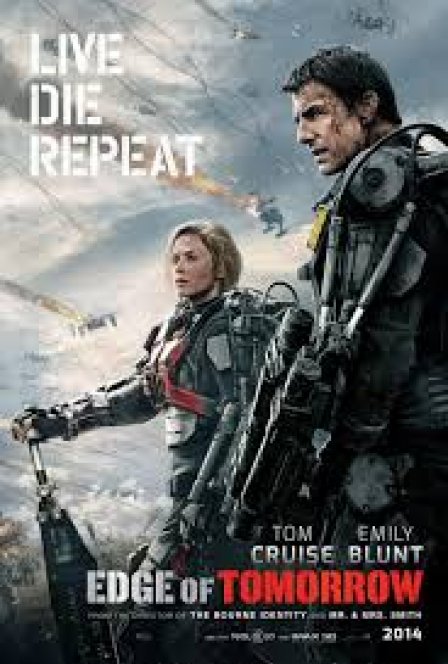

In the realm of public relations, Doug Liman’s Edge of Tomorrow is about two things simultaneously: the usefulness of Tom Cruise as an action star, and the financial potential of a would-be blockbuster adapted from source material the broader American public hasn’t read. (Hiroshi Sakurazaka’s 2004 sci-fi novel, All You Need is Kill.) The best thing about the film is that, as supremely self-aware as it is, it is single-mindedly devoted to its premise; that premise is almost incidentally a discourse on the trends and ailments of the contemporary blockbuster.

You probably know it by now. It’s refreshingly simple and explained with brevity and without dull portent. Bill Cage (Cruise) is an American military officer specializing in PR tactics. He is stripped of his rank and fed to a NATO-y international coalition as a grunt on the eve of a D-Day style invasion at Normandy, a last-ditch effort to fend off an invasion of “mimics” that has already claimed the bulk of Europe. Inept at combat and placed in a squadron of misfits and a hulking exoskeleton of ammunition, Cruise dies quickly on the front lines after a) killing a mimic of unusual hue and b) catching sight of Emily Blunt’s super-warrior, Rita. Upon realizing Rita is named after Bill Murray’s love interest in Groundhog Day, Cage wakes up to fight, die, and eventually love another day until he saves the world, or at least the first-world part of it. The film is a catalog of studio tics and preoccupations, with its empty gestures towards internationalism; its interest (cf. Pacific Rim) in fighting forces that blur the line between human and robot; its detour to a bucolic setting with Emily Blunt (cf. Looper); its jokes so canned they serve merely to end scenes instead of providing levity; its generic (albeit squirrely) alien invaders whose raison d’être is far from clear, apart from its attendant hope that the threat of global apocalypse might hold our attention.

Luckily, Edge of Tomorrow has built-in corrective measures for many of its technical and thematic clichés. The initial Normandy invasion is frantically edited and is borderline-incoherent in 3D, but we watch it over and over again and figure out the landscape along with Cage. The film’s script requires a whole lot of explaining — from the mechanics of time reset to the number of steps Cage and Rita need to take in order to avert mimics and falling airplanes — but the information is as much directed at its characters as it is at its audience. It knows that we know that death doesn’t matter anymore, so it mines some comedy out of repeated, gruesome, occasionally cruel murder. Cruise, our most utilitarian and physically dedicated action star, gets a role that suits his latter-day pragmatism, and our ambivalence about his persona; the film moves quickly enough that we can’t bother to muse upon his dedication to its love story, as we’ve been trained to do. We watch him die, and we laugh. We watch him wake up again, and we smile. Edge of Tomorrow takes a quick moment to, however perfunctorily, make us care about the fates of Cage and Rita, but its wonderful final reaction shot — a blink or two shorter than it would be in any other film — reads as much as a happy ending as it does an affirmation of our cultural literacy.

Liman’s canny referentiality would be irksome — unearned audience flattery — if it weren’t ultimately so relaxed and confident. This is the first sign in a while that we’re watching a film by the director who made Go way back in 1999: just as that film knew its audience had already seen Pulp Fiction, Edge of Tomorrow assumes a familiarity with first-person shooters and Groundhog Day. As such, the film is more fleet-footed than it has any right to be, hitting the reset button with willful abandon and moving it a clip just shy of unintelligibility. It breathes its referentiality instead of wearing it.