In Italian, the word ‘mammone’ loosely translates to the American English equivalent of “mama’s boy,” though, through the power of cultural coding, its meaning packs a far greater punch. The term has both provided fodder for comedians — for instance, Roberto Benigni’s Johnny Stecchino portrays the title character as both a cold-blooded mafioso and an excessively mother-loving son — and has also been the subject of more serious sociological commentary about the changing role of masculinity in the country. Just as Paolo Virzi’s film Caterina in the Big City sought to make humorous sense out of the mess that passes for politics in his homeland, his most recent work, The First Beautiful Thing, poses a serio-comic examination of the national myth of the mammone.

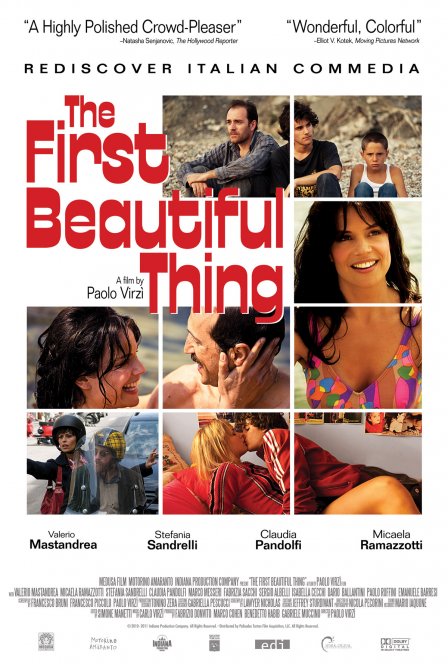

In 1971, Anna Nigiotti (Micaela Ramazzotti as the younger; Stefania Sandrelli as the older) is a young mother of two in the beach town of Livorno. From a young age, her son Bruno Michelucci (played at different ages by Valerio Mastandrea, Giacamo Bibbiani, and Francesco Rapalino) witnesses the effect that her grace and breezy personality have on the men around her, including his own father (Sergio Albelli), a police officer who forces the family out in a fit of jealousy. Cutting to the present day, the middle-aged Bruno teaches at a vocational college, occasionally dabbles in hard drugs, and refers to his longterm girlfriend as a “roommate.” When his sister Valeria (again, at different ages, Claudia Pandolfi, Aurora Frasca, and Giulia Burgalassi) informs him that Anna is dying, he is forced to return to the family he abandoned. Via intermittent flashbacks, we learn how the interplay between his mother’s sexuality and her doting attention towards her children has turned Bruno into the miserable lout he is today.

Through Bruno’s dilemma, Virzi forces the viewer to reconcile with the tacit question that underlies the mammone concept: Is a mother’s love really such a bad thing? While Anna dotes on Bruno, she sacrifices to provide for him and his sister. Indeed, Anna sometimes utilizes the power of her beauty to cut corners, but she never goes so far as to mistreat anyone, even those who seek to take advantage of her. The affection Anna doles out to her children seeps over into the world around her, just as the song she sings with them in two different scenes integrates itself into the film’s soundtrack (and provides the film’s title). Bruno’s contemporary state stems from his internalized feelings of disappointment, both in (falsely) believing that his mother lived up to the image of the gossips he overhears and from the idea that he has never lived up to her wishes for him as a poet. This self-inflicted punishment causes him to miss the plainly obvious fact that he has a pretty good life in his present day, just as his own father missed out on the fact that a plain-looking, foul-tempered country cop should have treasured a woman like Anna.

Ultimately, though, this commentary on the social phenomenon of the mammone segues to a more tempting interpretation. The relationship between Bruno and his mother provides a metaphor for the contemporary state of Italian film, which resides as the mundane offspring in the shadow of its exalted past. The change in styles between the scenes set in the 1970s, 1980s, and current day reflect this notion: the scenes from the 1970s have saturated colors that convey a dreamlike state, while those of the 1980s, a period in which Italian cinema’s began to decline (splatter fare aside), start to mimic the American studio comedy aesthetic of the time. Indeed, the 1970s sequences even include the presence of a Marcello Mastroianni stand-in, his iconic suit and shades seen in a split-second profile glimpse that summarizes the glories of yesteryear. Even Stefania Sandrelli’s presence in the present-day scenes serves as a reminder of this, her aged beauty no match for the vixen of her Il Conformista years. But her energetic performance also proves that all is not lost. Just as Bruno should accept the circumstances of his life, Italian film should accept the current state of cinema, focusing not on trying to recapture the grandeur of Fellini and Mastroianni, but on littler, more character-driven efforts. It’s no accident that Virzi has done just that, reminding us that modesty, after all, is a virtue as well.