Sophie (Miranda July) and Jason (Hamish Linklater), a 35-year-old couple who have been together for 4 years, are reclining against opposite arms of the couch in their Los Angeles studio apartment, their legs entwined in the intimate inconsiderateness that accompanies long-term monogamy. Jason shifts his position; Sophie asks, not looking up from her MacBook Pro, if he can get her a glass of water while he’s up. But he’s not getting up, so Sophie says it would be nice if they had a sort of crane that could transport a glass from the sink to the couch. Jason isn’t so sure — how would you turn on the tap? Sophie says with her mind. Jason says that it’s too bad that she can only use her mind to do things that she could do with her body; it turns out, he has a much cooler mind-power: he can freeze time. He demonstrates, and he and Sophie freeze. She sways a little too much. You’re really bad at this, he tells her.

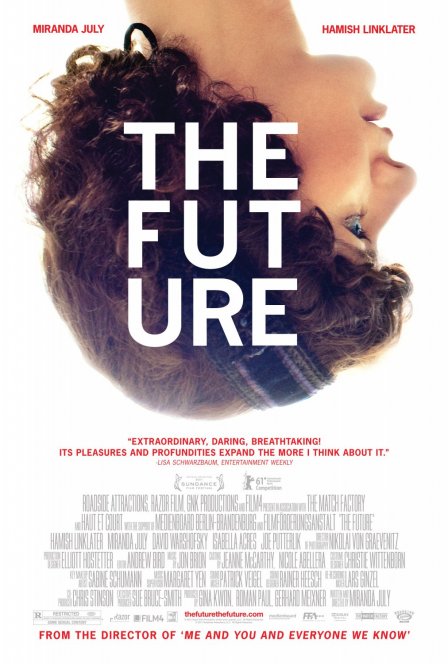

Read in summary, this scene near the beginning of The Future — the second film from writer/director/actress Miranda July — could be fuel for the legions who either dismiss (or hate) July’s work as merely whimsical and quirky, or praise her work for the same qualities. After all, she designs pillowcases with words on them. With their matching lank and unruly mops, surely the couple (unfoundedly referred to as “hipsters” by many reviewers) are lifestyle-signifying interior design items, too, extensions of the uniformly second-hand contents of their studio: cute potted plants, used books, ceramic hippos, and similar knickknacks.

But you might as well observe that The Future is shot in color. In July’s work, quirk and whimsy are narrative equivalents of a lisp — superficial mannerisms that say nothing important about the speaker, but loads about the audience’s ability to listen. Sophie and Jason, at least, are all ears. Couched beneath the conversation’s playfulness, each hears the notes of dread coming from their partner, from the bric-a-brac, or from somewhere in their apartment’s muted browns. July’s so agile a director, she could squeeze dread from puppies, and as actors, she and Linklater both excel in conveying opposing feelings simultaneously: in a single breath, there might be cheer, ennui, joy, fear, and desire. What’s troubling them here, it seems, is their inability to achieve what they would like with the talents they have (or don’t). The impossible paradox of wanting to stop time’s progression, while simultaneously wishing life — he provides tech support from home, she teaches dancing to preschoolers — weren’t so stagnant. In other words, the future.

Putting the shadows in foreshadowing, the scene’s a blueprint for how quirk begets darkness throughout the entire film. Yes, there’s an omniscient cat narrator (shown, mostly, as a close-up on a pair of adorable puppet paws), a talking moon, and a self-propelled t-shirt. But no matter how cheerfully fantastical these images seem, July always makes clear that what animates them is deeper and more powerful.

In her impressive, divisive debut, Me and You and Everyone We Know, a film about forging connections (no matter how inappropriate), July’s artifice showed us the hope in the grotesque — most famously, a kid who wanted to poop into an internet acquaintance’s butt, back and forth, forever ))<>((. Conversely, in The Future, which notably takes place after its characters’ intimate bonds are already well-established, July’s peculiar tricks reveal the terror in the familiar. In the Freudian sense, it’s uncanny (as Katrina Onstad observes in The New York Times): July’s mastery of tone makes even the mundane and quotidian seem indefinably off, producing a cognitive dissonance in the audience that’s often unsettling and sometimes terrifying. But for Sophie and Jason, it’s the familiar comfort of their lives, together in their apartment, that itself becomes untenable when they decide… to adopt a cat.

Paw Paw, the animal provoking their midlife crises, is currently recovering from a broken foot in the animal hospital. But upon his release, his renal failure will require daily care, cementing the couple into their current routine. But on the bright side, he won’t be around for long: only six months unless — the vet surprises them — they take good care of him, in which case he’ll live for years. Their looks of self-satisfaction melt. It’s a clever stand-in for a child (the better job you do, the longer your kid will likely interrupt your life), but the substitution makes Sophie and Jason’s ensuing panic feel more universal than the womb’s ticking time bomb. The cat could live for five years; by that time, they’ll be 40, which is basically the new 50, and after that it’s just “spare change”: something, to be sure, but not enough, Jason says, to get anything you want out of life. Basically, it’s all over.

Like countless characters before them, Sophie and Jason make radical changes when confronted with The End. With one month left till Paw Paw moves in, they quit their jobs to kind of follow their sort of dreams. They also turn off the internet. At least, Sophie does, so that she’ll stop wasting time looking — in a combination of horror and jealousy — at videos labeled “me dancing in my room” on YouTube. But before pulling the plug, the would-be ballet dancer emails all her friends to announce the magnum opus she intends to complete: 30 dances in 30 days, all to be recorded on her MacBook’s camera. Jason doesn’t have such lofty goals, deciding simply to just see what life throws his way, which turns out to be walking door-to-door for a well-meaning but dumb nonprofit organization whose goal is to plant a million (water-hungry) trees in (drought-struck) Los Angeles.

July has created a few well-known web art-projects/things, and she seems to be one of the few filmmakers today who actually understands the importance of the internet without freaking out over it. After all, without the internet, the characters’ lives aren’t much different. Sophie would have to go to an internet café to upload her videos (if she ever completed one) to YouTube. But more importantly, despite their disparity in aspirations, both she and Jason simply follow whatever opportunities — or diversions — present themselves, living their lives as if they were still aimlessly clicking on links.

For Sophie — who, in one of the most concise and heartbreaking scenes of artistic failure I’ve seen, abandons her silly 30/30 project and with it her self-worth — those links take her, circuitously, to a house in the San Fernando Valley’s suburbs and the bed of another man, Marshall (David Warshofsky). He wears a gold chain around his neck because it represents that he’s “ready to fuck,” and his daughter buries herself up to her neck in the yard for fun, but besides that, he and his household are so unremarkably normal it’s trippy. Just before they do fuck, Sophie holds her crotch against the arm of the couch for an uncomfortably long shot, as if it’s this life, not him, she wants inside of her. When it’s over, Marshall tells Sophie that he’d love to just watch her all day while she sits at home and does whatever. That would be perfect. She’d never have to try to do anything, she says. It’s even easier than getting hits on YouTube is the implication.

Refreshingly, the midlife crisis — usually male territory — is much more Sophie’s than Jason’s. But he still gets a new man in his life, too, after he responds to an ad in the Pennysaver from an octogenarian named Joe (Joe Putterlik) who’s selling a refurbished hairdryer for $3. Although Joe plays himself (July met Putterlik through, yup, an art project about people who still advertise in the Pennysaver; he died the day after she finished shooting), his scenes are definite highlights — especially when he unselfconsciously reads one of the obscene limericks he’s written on handmade collage cards for his wife of 60 years for every holiday (July’s always excelled at not differentiating between perversion and poetry).

Joe is The Future’s sage of sorts, reaffirming Jason’s belief in his troubled relationship and allaying his fears about life after 40. Joe provides the voice for the moon, too, which gives Jason advice after he stops time for reals upon discovering Sophie’s infidelity. But in The Future, one of the most unrelentingly devastating films in memory, solutions don’t come from the wisdom of old folks or from anything else. Not even catharsis.

From Jon Brion’s indispensable score to Miranda July’s character’s performance-piece-worthy dances, The Future is unbelievably original. But its closest relative — in spirit, if not aesthetics or tone — might be one of cinema’s most well-known: Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, which shows a couple fall in and out of love (and then die) with incredible realism (it’s so long it almost feels like it happens in real time). Both films create crushing devastation out of everyday monogamy, love, and mortality. July’s more expansive in her thematic scope, but more importantly, she never gives the audience the catharsis of a cinematic pummeling like a brutal argument, falling out of love, or the death of a character. In Scenes from a Marriage, the terror is always immediate, even when it’s growing old and dying. But in The Future, the immediate is never so bad. There’s no possibility of relief, since it hasn’t happened. And it never will: the future might be death, but it will never be the present.

Filmmakers have been fascinated with time since there have been films: bending it, compressing it, reversing it, drawing it out, and making it perform all kinds of technical tricks. But perhaps no film has more rigorously explored our emotional relationship with it. Turns out, it’s a brutal one.