God’s Pocket is a place. I’m not sure where. It’s a lower class Irish neighborhood in some American city, and this story — similar to a lot of others in the area — presumably takes place in some recently-happened past, when people still read newspapers every morning instead of their computers, and when people gossiped at bars and not on Facebook. Maybe it’s the 70s. You can almost hear the the voice over: “There are eight million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them.”

It revolves around a 23-year-old, Leon (Caleb Landry Jones), who dies at work, at a factory of some kind or another, where there’s a yard and lots of cement bricks. Leon’s spouting off like the wanna-be tough guy he is, doing his best De Niro, “You talkin’ ta me?” He’s telling some story. There’s an ancient black man sitting behind him (Arthur French), head thick with white hair, who makes a comment under his breath, and Leon turns around, calling him a nigger, asking him what he said, holding a razor blade to his throat. When Leon lets up, the old man takes his opportunity and swings a lead pipe at Leon’s head, killing him. When the cops show up, the other workers — maybe rightfully, maybe it doesn’t matter — tell them that something fell on Leon’s head and it was a simple accident.

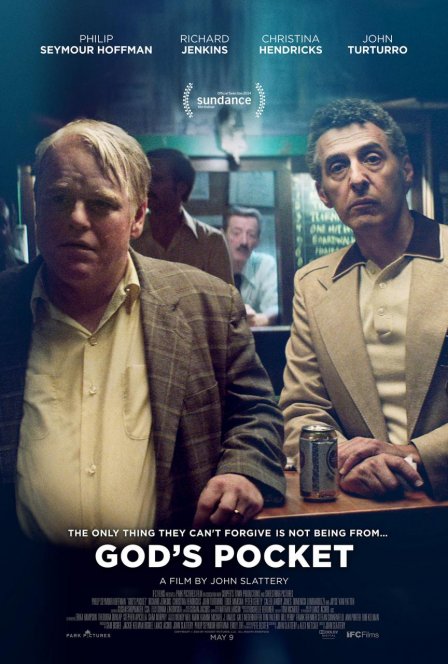

Leon was a piece of shit. Richard Shellburn (Richard Jenkins), a newspaper columnist who writes about God’s Pocket, knows as much, says as much, pisses people off as much. His dad, Mickey (Philip Seymour Hoffman), sells meat but is involved in some organized crime; he steals things and still has no money, all of it undoubtedly trapped in the endless cycle of his next score. Leon probably turned out bad because his parents were bad; Mickey doesn’t seem like a terrible person, in that he tries to help people more than he tries to hurt them. But, then, he still hurts them. He’s trapped. Most people who commit crime are.

Largely, God’s Pocket is about watching people’s undoing. Bad things keep happening, especially to Mickey. Everybody believes good things ought to be coming to them, greedily; that’s why bad things keep happening. I wanted to watch these characters succeed, even at the downfall of others. They don’t. That is not this story.

This story and these characters are indistinguishable from anything else; with eight million stories left untold, how can we live without letting it all become background noise? At one point, Shellburn sits in his car at a stop light poeticizing his life writing about God’s Pocket into a tape recorder: “I’ve loved this woman for 20 years. Last night, I laid beside her… I know her…” He’s sipping beer and losing his train of thought, and kids in the car next to him yell over to make fun of him. He is unfazed. To his readers and the people around him, he is a documentarian of something that has massive importance, while to everyone else he is a nobody. Mickey’s wife (Christina Hendricks) reads him a clip from Shellburn’s column and Mickey says, “I don’t know why writin’ down what everybody already knows is better than known’ in the first place.”

As much as God’s Pocket feels familiar and worn, I can’t place another movie that’s exactly like it. The story is forgettable, like most things and most stories; it’s barely there, and picks up momentum slowly, if at all. The characters have little background, but are played well by a cast that any ninth grade cinephile leading the campus film club can tell you is fantastic. The traction they have on your sense of empathy is due to the heavyweights around the ring, for sure. But I like worn out things, too; clothes that are familiar just seem to fit better. I enjoy that. Not everything has to be a reinvention. There’s something to be said for making another in an established line products adequately, if not well.