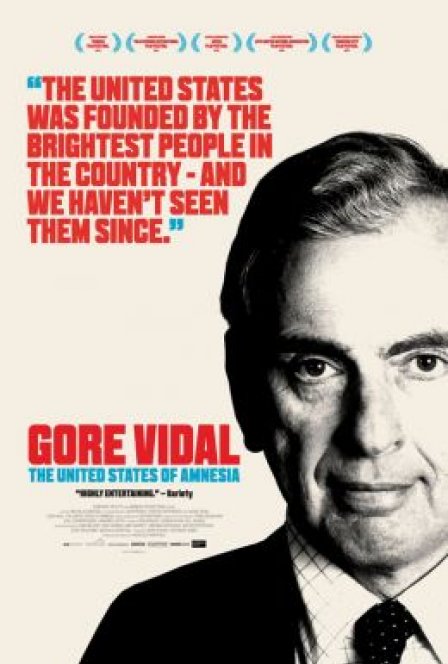

Gore Vidal: The United States of Amnesia is the sort of fawning documentary that we might expect to find on late night basic cable. Director Nicholas D. Wrathall’s approach is straightforward and frustrating: he cobbles together interviews and archival footage, all of which are meant to laud one of America’s preeminent twentieth century intellectuals. There is little attempt to investigate the man or his flaws; in fact, the sloppy journalism of the documentary raises more questions than answers, and there’s the sense that it will not do much to sway Vidal’s detractors. The United States of Amnesia positions Vidal as an iconoclast, yet it does not entirely make the case he’s a unique one.

Admittedly, my first exposure to Vidal was not his novels, his essays, or his now-infamous debates with fellow intellectual William F. Buckley. I first saw him in the films With Honors and Gattaca: in both Vidal had a minor role as a snobby professor, and his aristocratic cadence was a perfect fit for the subject matter since his characters were deeply cynical about human nature. The performances do not require a lot of Vidal, as his coming from privilege and his snooty dismissiveness were important parts of his character.

Vidal’s father was a higher-up in the Roosevelt administration, and his grandfather was an important Senator. Vidal was friends with the Kennedys and Paul Newman, and he wrote his first novel before he was twenty. The documentary is a highlight reel of Vidal’s early life, with a focus on his time in Italy with his partner Howard Auten. Wrathall shifts gears for his later life, and attempts to develop how he was a soothsayer who was correct about everything from the surveillance state to Reagan to inequality. There are also Vidal’s two failed attempts to run for public office, but the talking heads whitewash his failures to the point of suggesting they’re secret victories. There are interviews with Vidal in his twilight years — he was eighty-four when he passed away in 2009 — but without a timestamp to provide context, it is difficult to determine the evolution (or lack thereof) in his thinking.

The two most interesting things about Vidal deal with how his opinion flipped on important men in his life. The first one involves the documentary’s most fascinating few minutes: Vidal is deeply candid about his opinion of President Kennedy, and we see his sharp mind at work when he’s able to separate the man from the politician. The murkier flip-flop involves the late Christopher Hitchens, who Vidal once declared as his unofficial heir. Vidal reverses his decree, and it’ts unclear whether it’s because Vidal was afraid of death or because Hitchens switched sides and became a neocon. Annoyingly, Wrathall does not care to investigate. He shows a couple interviews with both men — again, not making clear when they took place — and without a timeline the cumulative effect is rather petty.

All of the talking heads in The United States of Amnesia are universal in their praise of Vidal. His colleagues think he’s underrated, his contemporaries think he’s a genius, and his celebrity friends are in awe of how popular he is. Of course, there are significant sections in the documentary that amount to little more than highbrow gossip: there’s a story about how Paul Newman nearly beat up Buckley on Vidal’s behalf (to Newman’s credit the threats were justified, as Buckley had the gall to discuss Vidal’s homosexuality* on national television in 1968). There are fun anecdotes — some of them are downright delicious — yet they’re ultimately superficial since there’s no attempt to drill down into Vidal’s life. He had famous feuds with Truman Capote and Norman Mailer, for example, and the stories and archival footage make no attempt to explain why. Clearly the documentary is not meant for Vidal’s long-term fans, so the lack of an explanation is a failure on the part of the filmmakers.

At a trim ninety minutes, the documentary gives little sense of Vidal as a man. He’s clearly intelligent and has a finely-tuned sense of moral clarity, but this an exercise in mythmaking, not journalism. While the breadth of Vidal’s social life is astonishing, the biggest surprise of Wrathall’s documentary is how his subject does passable impressions of Reagan and George W. Bush. This documentary is so bad that it ends with an unintentionally hilarious truth-bomb from Vidal, one that’s meant to sound incendiary and instead serves as a reminder that acting like a blowhard is the last weapon in any intellectual’s arsenal. Good documentaries experiment with form or make an attempt to develop nuanced profile of a man or issue. Gore Vidal: The United States of Amnesia accomplishes neither, and instead inflates the ego of a man who’s no longer around to appreciate the effort.

*While Vidal was critical of Reagan’s charm and young men dying in Vietnam, he was never an advocate for the tens of thousands of gay men who died of AIDS. A biographer openly acknowledges Vidal was a self-loathing homosexual, something the documentary doesn’t dare mention.