There is no heterosexual sex in Humpday, the third feature by director Lynn Shelton. But that’s not for lack of trying. In fact, there are no fewer than three attempts, foiled by fatigue, then anger, then a giant, terrifying dildo. But it’s not the girl-on-boy stuff you’re here to read about. You’re more interested in the film’s central sex question: Do the two dudes get it on, or what?

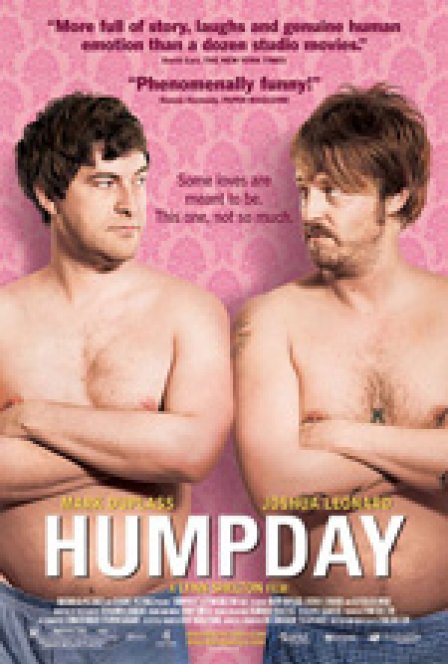

This is the query that has fueled most of the film’s buzz since its Sundance premiere. In case you haven’t heard, the newest entry in the dubiously-named “mumblecore” genre takes the stupidly popular bromance plot to an entirely new level. When Andrew (Joshua Leonard) unexpectedly shows up in the dead of night to visit his old friend Ben (Puffy Chair and Baghead filmmaker Mark Duplass), it’s clear that trouble isn’t far behind. In the decade that has passed since their wild college days, Ben has married Anna (Alycia Delmore) and settled down with an office job. But Andrew seems crazier and freer than ever, careening around the world in search of new adventures. The men have grown chubbier and less satisfied over the years, and it seems that each sees something enviable in the other’s life.

Despite her confusion at Andrew’s arrival, Anna resolves to get to know Ben's friend and make him feel welcome. Unfortunately, her efforts all go to shit, as Ben joins his friend for dinner at the house of some hypersexual artists who Andrew hopes to bed. Intending to only stay for a short while, Ben gets drunk and stoned and returns home in the wee hours of the morning, as Anna sits forlornly at home, with a table full of uneaten pork chops. And Ben’s transgressions don't end there: The same night, egged on by his new friends, he agrees to have sex on film with his old buddy for a local art-porn festival.

Of course, Anna inevitably finds out about the plan, despite Ben’s evasions. And although most of the couple’s interactions often seem overly awkward – no doubt a conceit of the genre, but even so, the stilted dialogue often transcends Ben and Anna’s communication issues to enter the realm of poor scripting – her blow-up and their eventual heart-to-heart present a rare, bluntly honest treatment of contemporary relationships. When Ben tells Anna that he needs to make the film because their marriage has caused him to lose the sense of adventure and possibility he had in his youth, she points out that he’s speaking to her “as though I’m a cardboard cutout that just stands in the kitchen and makes dinner.” Then, she goes on to reveal an unexpected transgression of her own.

At certain moments, Shelton is prone to belaboring more than just dialogue. The artists Ben and Andrew fall in with are utter caricature, lying around a house they've dubbed 'Dionysus' in various states of undress, casually engaging in all sorts of pansexual hijinks. Their pseudo-intellectualism is nothing short of nauseating. Now, I realize that Humpday is supposed to be a comedy (and it is, sort of), and we’re supposed to find their antics funny, but a film that prides itself on its hyperrealistic style would be better off forgoing such broad strokes for a subtler brand of humor.

Where Humpday really excels is in its depiction of Ben and Andrew’s relationship. After so many years apart, they speak easily and candidly to one another, but Andrew overestimates how square his friend has become, and Ben buys in a bit too heartily to Andrew’s self-made myth. While they seem, at first glance, to be taking their dare too seriously, the plan to co-star in a porn film carries on its back the egos of both men. Ben’s burden is obvious: He needs to convince himself that he’s not just another Middle American soon-to-be dad, doomed to live a life of quiet desperation. But what’s nagging at Andrew is just as serious. Although he calls himself an artist, he has never finished a work, and he begins to view the film as his final chance to do so. Shelton and her actors paint a convincing portrait of two men stuck in entirely different ruts who must either do something that terrifies and disgusts them or resign themselves to remaining eternally unsatisfied. (Remember when I said it’s only “sort of” a comedy?)

I credit Shelton’s generally shrewd plotting and directing for introducing the thought that kept taunting me as I watched Humpday: If it means so much to both of them to carry out this hair-brained plan, then why can’t they just stick one body part in another and be done with it? Is it really so difficult? That their undertaking pushes enough boundaries to actually, potentially, qualify as art makes us wonder why men (at least in this culture) are so disgusted by each other’s bodies. Why is it such a struggle for two dudes to get naked together when people eat live tarantulas or whatever on TV? It is these gnawing inquiries into human relationships that the best “mumblecore” films – such as Joe Swanberg’s Nights and Weekends and his web series Young American Bodies and Andrew Bujalski’s Funny Ha Ha – excel at. They transcend their humble production values and improvised scripts to get at some small, resonant truth about the way we relate to others (or fail to do so).

Humpday explodes its self-posed questions to mind-bending -- and, yes, sometimes silly -- extremes in its final scene, which takes place in the hotel room where Andrew and Ben have agreed to make their movie. I will tell you this: When the men leave the room – apart – I don’t believe they’ll ever see one another again or experience a friendship as intimate as the one they once shared. But as for the “do they or don’t they?” question, well, I want you to see this movie, so I won’t be letting you in on that secret.