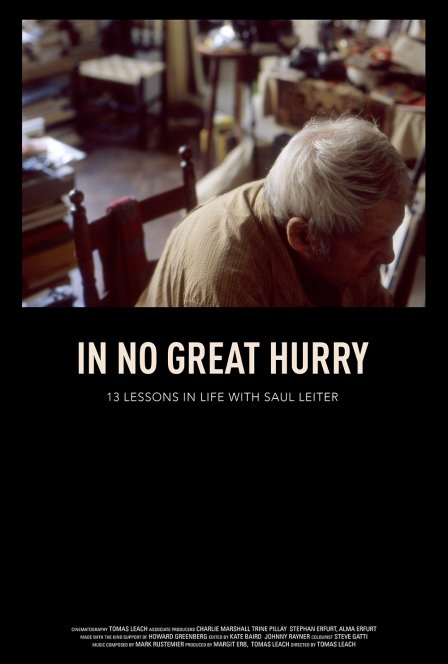

Perhaps Tomas Leach knew he was creating an elegy for Saul Leiter. The street photographer died last November, a week shy of his 90th birthday and not too long after the completion of Leach’s documentary, In No Great Hurry: 13 Lessons in Life with Saul Leiter. But in the film, Leiter is still very much alive. Yes, he walks slowly, his head bowed forward. And he sometimes halts mid-sentence as though his thought snagged on a mental nail. But he’s feisty and funny and self-deprecating. (“You know, you walk down the street and… you look in a window and there’s this old guy walking along with you and you realize that’s who you are!”) Mostly Leiter is baffled by Leach’s persistent desire to film him. But it quickly becomes apparent that he is an eminently worthy subject.

For the uninitiated, Leach begins with a brief reading by art historian and critic Max Kozloff, who places the artist “at the top in the Mount Olympus of New York photography… he’s right up there with the amazing heights of photographic history itself.” Leiter shot in color long before it was fashionable, let alone accepted as an art medium. After inclusion in two Museum of Modern Art shows in the 1950s, he worked in relative obscurity, making a living shooting fashion photography. Only in the early 2000s did his street photography begin earning the attention it deserves. As Kozloff speaks, we see a slideshow of photos. Their straightforward titles — “Snow,” “Street Scene,” “Newspaper Kiosk” — hint at Leiter’s humility, but belie the depths of his artistry. Leiter, who is also a painter, finds a vibrant color palette hiding among New York’s grays and browns. In tightly composed frames he creates abstraction in the everyday without obscuring familiar elements.

The film’s “lessons,” a baker’s dozen of gnomic titles, are pulled from the ongoing dialogue between subject and filmmaker, a conversation that ranges from Leiter’s personal biography to the pretensions of art photography. Leiter lived in Manhattan’s Lower East Side for more than 60 years and photographed the neighborhood for just as long. So it might seem strange that most of this discussion takes place inside his apartment — until you see the place. It’s as beautifully busy as his photos with boxes and papers and Leiter’s own paintings cluttering every surface. He sits by the wall-sized window where he paints and Leach sits across from him. He holds the camera without a tripod, a clever choice that promotes intimacy. Sometimes Leiter speaks directly to the lens. Occasionally, the camera jumps around when Leiter makes Leach laugh.

Throughout the film, Leiter makes an effort at organizing his apartment, aided and encouraged by Margit Erb, his assistant and friend and the film’s co-producer. But his progress moves in fits and starts. In each box, he finds things that stir up memories that send him veering off track. Sometimes the morass is simply too overwhelming and he gives up and makes coffee.

If the idea of watching an old man sift through dusty boxes sounds unappealing, don’t forget that Leiter is a wry sage. Here he is on messiness: “To be in a state of pleasant confusion sometimes can be very satisfying. Especially if you’re slightly crazy.” On remembering the past: “I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it. Maybe I do more than I think I do. Maybe I do everything more than I think I do. Maybe.” On certain photos: “When Margit sometimes says to me, ‘That’s not really you,’ I sometimes wonder, ‘What is really me?’” On Leach (who lives in London): “He comes from Europe and tortures me — and I was hoping to be forgotten.”

But Leiter isn’t all salt. He has a wistful streak, particularly when talking about his longtime love, Soames Bantry. She died in 2002 and years later he hadn’t yet cleared out her room. “I didn’t go into it — maybe I couldn’t bring myself to alone. Maybe at times it seemed impossible to me to deal with.”

Given the film’s simple framework, it’s easy to underestimate Leach’s contributions, not the least of which was convincing Leiter to participate. (In the film, the photographer only half-jokingly claims permission is contingent on a screening: “Maybe when I see it I’ll think, ‘Oh my God, that’s very bad.’ I don’t know.”) Leach is also patient without sacrificing intention. The conversation wends here and there and pauses linger, but we never feel lost. His restraint is matched by Mark Rustemier’s sparse and plaintive original music (which is often strikingly reminiscent of Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel).

Leach also gives the film’s conversation room to breathe with occasional walks around the neighborhood. On these wanders, Leiter, camera hanging from his shoulder, sparkles with curiosity and delight. In one scene outside St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, Leiter casually snaps shots of three young women sitting on a bench eating ice cream. Leach leans over to see the digital preview on Leiter’s camera: the frame is just their symmetrical crossed legs, an elegant geometry of diagonals and gentle curves.

The moment is tantalizingly fleet. You want to see more of Leiter in action. And sometimes, Leach could get closer to the work, particularly in one instance, when Leiter holds up some old prints. But he’s close when it matters. At one point, Leiter braves a venture into Soames’s room with Leach in tow. He finds a collection of hand-painted paper he used to wrap gifts for his love. She saved them without his knowing. He’s ready to get rid of them and then reconsiders and puts them back. “It kinda tears your heart out, if you know what I mean, if you have a heart. If you don’t have a heart, you’re very lucky.” Perhaps it was Leiter who composed the elegy.