It’s hard to grasp that the concept of “childhood” is a relatively recent invention. If you’re under 18, you’re regarded as the beacon of innocence and naiveté, with an almost entirely separate set of laws, institutions, media, and markets directed at you. But what really makes childhood seem so unquestionable is less about how we’ve come to define youth itself and more about how we’ve come to use childhood to define adulthood. It’s a co-dependent dichotomy, the likes of which might only be surpassed by our constructions of masculinity and femininity. Yet all this is quite a change from the pre-renaissance perspective, in which children were simply smaller, weaker, less-experienced adults. While it’s not like medieval Europeans had a worldview worth emulating — women were property, bathing was weird, and we humans do take a stupidly long time to develop — you only have to catch sight of an Anne Geddes calendar to wonder if maybe this whole thing really has gone too far.

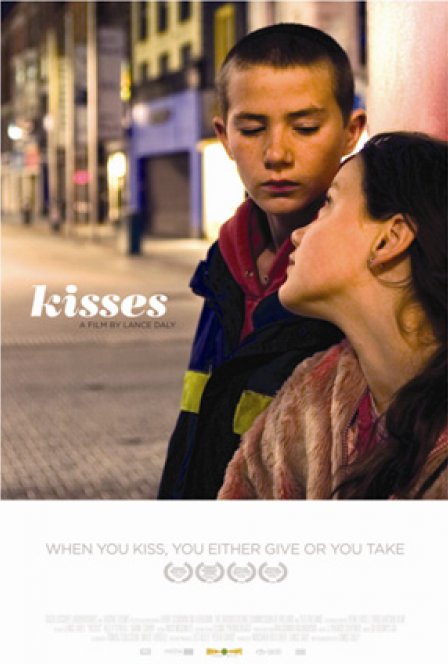

In its best moments, there’s something slightly medieval about Kisses. Its protagonists, the barely double-digits Dylan (Shane Curry) and Kylie (Kelly O’Neil) roll around on heelies, gorge on candy, and wrestle on an abandoned ice rink, but they also swear, swap spit, fight off perverts, and witness the treacherousness of the late-night streets of Dublin with a stoicism well beyond their years. It’s a refreshingly non-idealized vision of childhood, or perhaps the lack of one. There’s no child/adult dichotomy here, and writer/director Lance Daly doesn’t seem to pity the kids for this lack: like the shriveled baby Jesuses in pre-renaissance paintings, Dylan and Kylie are just adults who got shrunk in the wash.

Kisses opens as the two young neighbors try to survive Christmas vacation in their dysfunctional households in a desolate Dublin suburb. Dylan plays videogames to drown out his father, who uses threats of violence to solve all his disagreements with everyone from Dylan’s mother to the toaster. Kylie tries to dodge her overworked mother, menacing older sister, and very affectionate uncle. These kids should probably be put up in foster homes or something, but Daly respects their autonomous little selves too much to suggest that domestic abuse is anything they can’t deal with on their own.

He even finds room for humor in this environment. Working in gritty black and white, he pays careful attention to the inhuman design of the suburban landscape. Against this backdrop, when two bullies pull up out of nowhere on pint-sized scooters just to tell Dylan to fuck off and a carriage-pushing trio of ultra-trashy young girls tease Kylie about not having fucked yet, the film squeezes bleak, absurdist humor out of bleak, depressing realism. They’re admirably complex laughs for a movie about the budding relationship between two runaway kids; under the same circumstances, I’d imagine most directors would opt for the “Kids Say the Darndest Things” chuckles, but Daly never plays the cute card.

Still, this humor disappears as quickly as Dylan and Kylie do, when, worried for their lives after defying their respective parents, they run away. After a brief hike through the post-industrial fringes of town, they hitch a ride on a weird little boat and end up in Dublin. Once there, Daly’s attention to landscape and environment all but vanishes — lost, I suppose, in the city’s narrow streets along with most traces of the film’s humor.

Those aren’t the only changes that occur when Dylan and Kylie enter the big city. Sometime during their arrival in Dublin, the film changes from black and white to color. It’s not a dramatic difference, and you might not even notice the change at first, but it’s still unnecessarily reminiscent of a film starring a certain Dorothy. And, like that film, with color comes music, which comes in the form of street performers, Bob Dylan references, and lots of clumsy montages set to a distracting soundtrack by Go Blimps Go. Factor in a cheesy chime sound and burst of light that happens when the film’s titular kisses occur, and, sadly, you have a magical realist reworking of The Wizard of Oz.

It’s too bad that these aesthetic missteps mire Daly’s film and a pair of great performances by Curry and O’Neil. Another reason baby Jesuses looked like tiny old men back in the day: painters just didn’t have their technique down.