Klown is a Danish buddy movie, a surreal, caustic romp that can plausibly claim both Todd Phillips and James Dickey as spiritual forefathers. The proceedings involve a fair amount of questionable moral and genital behavior, as well as a healthy portion of male and female nudity. To wit: a sex comedy. Far from indulging in a straightforward raunch-fest, though, Klown pulls off the trickier feat of couching its laughs in a bold and cynical critique of modern masculinity.

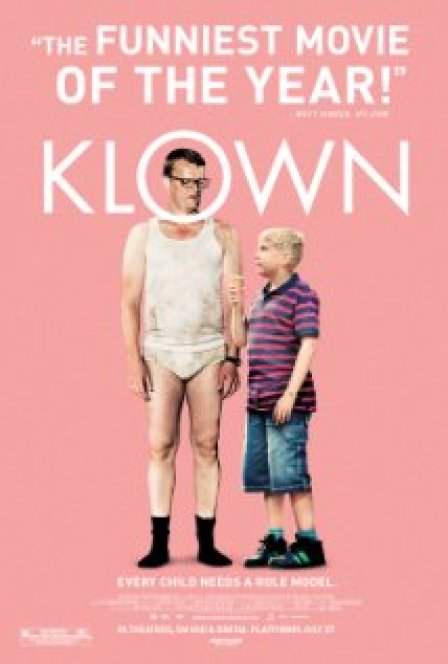

Things get underway when Frank (Frank Hvam) discovers that his girlfriend Mia (Mia Lynhe) is considering terminating her pregnancy. Mia, it seems, isn’t convinced that Frank is dad material, and it’s easy enough to see why: he’s a spineless, petty milquetoast, and beyond that has made it clear that he does not wish to procreate. “If I wanted kids around,” Frank smugly remarks, “I’d have worked in a kindergarten.” Things are made worse when, having been left in charge of Mia’s nephew Bo (Marcuz Jess Petersen), Frank abandons him to his fate during a home invasion robbery. In a last-ditch effort to save his relationship and repair his bruised ego, Frank decides to semi-kidnap Bo and take him on a canoe trip with his friend Casper (Casper Christensen). Casper is furious: he had planned the trip as an excuse to visit a high-end bordello while sampling the local fare all the way up the river, in an expedition dubbed the “Tour de Pussy.” But despite his protests, he is goaded into taking Bo along.

The trio’s river-bound misadventures make up much of the film, as Frank and Casper bicker about this and that and stumble into impossible situations. Bo is a mostly silent observer to the various travesties that the two adult men commit, even when they are ostensibly acting on his behalf. Frank makes a few halfhearted attempts to become a father figure to Bo, and to convince himself that he can step up to the plate, parenthood-wise. But these efforts are usually derailed by Casper’s ill-advised adventures in coitus, or by Frank’s general ineptitude and small-mindedness.

It is the questionable motives of Frank and Casper more than their despicable actions, though, that ultimately keep Klown afloat. Frank’s despairing attempts at child care and Casper’s raging libido-on-sleeve machismo are merely sad feints toward what each man perceives to be the masculine ideal. Klown’s comedy is at its keenest when these efforts flail around and gasp for air, or show up dead on arrival. This is perhaps why the film loses its bite when the boys return to dry land, and Frank goes for a last-ditch shot at redemption. It’s far more entertaining to watch our heroes barely make an effort — or, better yet, try like hell for all the wrong reasons and still fail.

Rather than ciphers or straw men to be shot down for our amusement, however, Frank and Casper feel like familiar, if slightly exaggerated, reflections of run-of-the-mill human failings. Much of Klown has an uncomfortable, clammy feel to it, and not just because of the warts-and-all sex scenes. Sure, Frank and Casper are absurd, but their more defining character traits spring from real and identifiable insecurities. Klown is often surgically effective at laying bare these self-doubts and uncertainties, and it is at those points that the film elicits both the loudest laughs and the deepest cringes.