People love love. That’s why my tinder profile is [much] more carefully curated than my C.V. and I’ve been pretending to be into astrology and Drake for the past four years (N.B. date me). It is better to have an entirely new personality to fool the world into loving you than never to have loved at all. The overwhelming taboo surrounding romantic independence drives The Lobster, the latest low-key, high concept black comedy from Yorgos Lanthimos. In this us-but-slightly-different universe, if you haven’t found your “suitable partner” by a certain age, you’re turned into an animal. The pursuit of love isn’t just aspirational; it’s mandated. It’s also laff-out-loud funny as translated in film’s absolute apathy, which might be oppressively bleak were it not so consistent with its low emotional intelligence. Collin Farrell’s puppy-eyed David has 45 days at a soon-to-be couples’ resort to find his match before he is turned into the titular lobster. The conceit is a winning one, but it’s mostly a dim flashbulb illuminating The Lobster’s wry commentary on the lengths we are willing to go to find that special someone (please slide into these DMs). In an uncluttered look at the conventionally fraught language of love, The Lobster dehumanizes the very myth that separates man from crustacean.

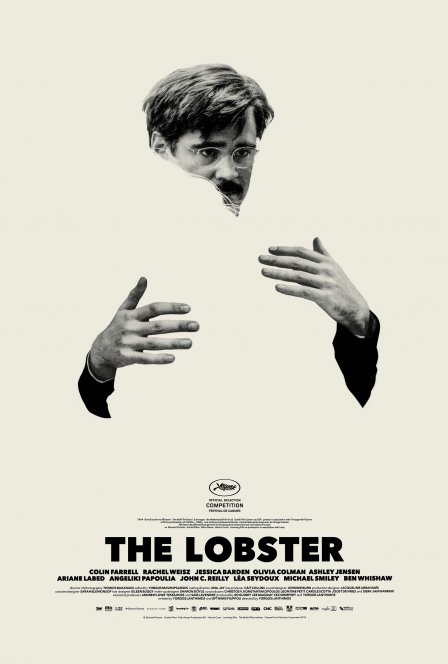

Recently split from his wife of eleven years, David is once again thrown into dangerous singledom, and the countdown begins until he joins his brother (and much of this world’s population) in a new life as an animal. The hotel in which he searches for love has all the amenities for romance: uniform rooms and dress, eerily milquetoast entertainment, therapeutic hand jobs from the staff, endless rules and regulations. There’s squash games and the nightly outing of hunting “loners:” outcasts who have opted for life in the woods over governmentally mandated domestic bliss. The love peddled in the hotel is one comically mechanized, where a potential meet-cute is most likely in the discovery of a shared physical flaw. Limps pair with limps, lisps with lisps, chronic nose bleeders with others who know their way around oxyclean. David, paunchy and sad-dad mustachioed, can’t seem to find anyone with his particular set of characteristics, so he adopts the implied sociopathy of a potential partner. As she presciently notes, “love cannot be built on a lie,” and their romance ends in a tragic (and very disturbing) turn that leads David to escape amongst the hunted loners.

There, he meets his suitable partner in Rachel Weisz’s nameless loner, who shares his short-sightedness. Love is strictly forbidden amongst loners, and so the pair formulates a silent language to organize their trysts and learn about each other. In a film where language flounders like me on a first date (check your local bathrooms for my number), their secret tongue is the only communication that works. Much of the talk surrounding love in the film is built on lies and legend — delivered in unrelenting deadpan — but written in the clunky declaratives of a robot or a child or an undergrad scripting a one-act. It is this that makes it so hard to distinguish truth from lie, fact from myth, callousness from simple detachment. Weisz’s insistent voiceover narration, both wholly omniscient and comically redundant, draws attention of the inability of language to account for the nuance of connection that ties idea to actuality. So when language becomes purely gestural, David and the short-sighted woman can finally speak, cultivating a bond that goes beyond their shared inability to read small print. And in the logic of the film’s loose allegory, loving pre-linguistically is a neat loophole between animal and human couple. Does that mean they can make it work though? Probably not — you see how gloomy that trailer is? SEGUE SEGUE CUE CINEMATOGRAPHY, BABY: It’s beautiful to look at, but the visuals carry the same note of redundancy as the narration. The now-cliché shorthands for the uncanny of alternating center-framed minimalism and kitsch, of vignetted performers, of lush forestation in sparing slow-motion compose a visual corollary to the committed detachment of the story. It’s pleasing but unoriginal, like the hotel-art matter-of-factness of the dialogue.

There are a lot of fucked up love stories that could use The Lobster’s clever and endearing make-under. I-I-I-I I thought of that, uh, old Woody Allen scene — you know, in Annie Hall — where the piece of shit human gets the girl by fooling generations of women into thinking that love need be a fumbling adventure in rescuing an art-damaged puppy. It’s a dangerous notion, and one that The Lobster evades by having nothing like “the lobster scene” or any other iterations of the endless examples of crazy, stupid love. Nothing about love in The Lobster’s universe is ineffable until David discovers that he needs a new language to express it. The Lobster’s love is not a concept but a wholly articulated and tangible thing, like a hunting trophy or prescription glasses. To hear it put so bluntly seems like a callous dismissal of connectivity, but is instead a call to love “love” less and each other a bit more. Pardon the gooey-ness, but an hour and fifty-some minutes of deadpanned “I love yous” and dead dogs has me overcompensating emotionally. The standards to which we hold love are silly, short-sighted things, that negate the possibility of being just two short-sighted pups or lobsters or me and you, reader (seriously call me), in love.