I hope I die before I get old. Like, actually. Can you even imagine getting old? I don’t mean kids-and-a-mortgage old, but like approaching-death old. Half a flight of stairs tires you out, your teeth fall out, your body decays, you forget where you are, no more boners. On top of all this, the world undergoes radical changes — a resentful youth takes over with their own wishes and standards, making you an enemy and an outsider. And when they talk to you they call you “young man” or “young lady” in seemingly innocent and kind ways that are really just patronizing and deprecating. But what’s worse than all of this is the empty time that comes from a life of retirement. Time that can be spent on reflection — regrets and guilt have more time than ever to manifest in horrible and destructive little ways. The best you can hope for is that you die before your partner (if you’re lucky enough to have a lifelong partner), or at least that you die before your loved ones grow tired of caring for you.

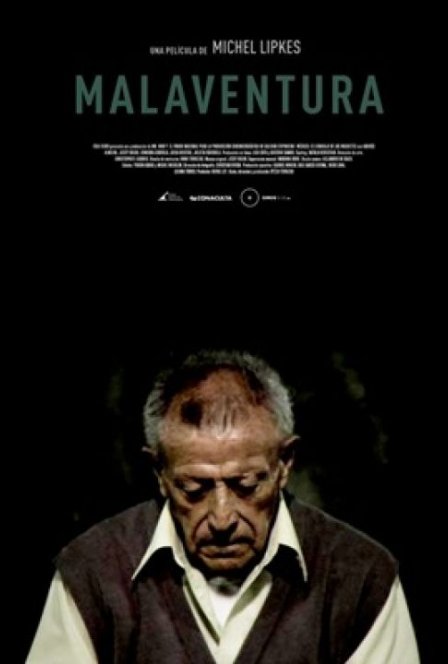

Malaventura is first-time director Michel Lipke’s examination of old age, oncoming death, life and regrets. The film spans the events in a single day of an unnamed old man left alone in the world (and manages to cover those themes with much more grace and dignity than the opening paragraph of this review). The very first scene establishes the tone and pace for the entire film: over a single, static shot lasting nine minutes, the old man wakes in his bedroom and completes his morning routine. Actions unfold deliberately but slowly, with patience and a sense of routine throughout. The rest of the film continues this way, as the old man wanders the streets of Mexico City.

The first scene that really breaks with the idea of routine is one inside the porno theater. The old man arrives at the theater, probably “inspired” by the beautiful, youthful girl he saw on the train earlier in the day. But within moments, as soon as the film he’s watching becomes sexual, shame and embarrassment take over. He hangs his head and slowly exits the theater. The scene continues to play in the background; the combination of pleasure moans (screams) with fragmented images of pubis and penetration creating an uncomfortable experience. (Note: the scene is especially effective if you’re watching at home, in a dark bedroom, with your roommate and his girlfriend listening across the hall.)

Scenes like this, along with a later one taking place at a bar populated by elderly patrons where a man recites lines from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, showcase non-actor Isaac López’s many somber expressions. The film, which hinders on his ability to silently convey guilt, terror, sadness, and disgrace, gains tremendously because he brings his own experiences and memories to the performance. There are memories there, under his skin, but they are left ambiguous to the viewer. As the film reaches its finale, the old man’s guilt and shame escalate until they reach a violent and surreal apex, breaking with the otherwise mundanity of the film. But it’s too little too late: the film’s reliance on fragmented, minimalist narrative leaves little in the way of understanding the tragic ending. Then again, maybe that’s the point. With age, you finally come to terms with the fact the world is an indifferent place and you can’t and won’t understand everything. Man, I don’t wanna grow up.