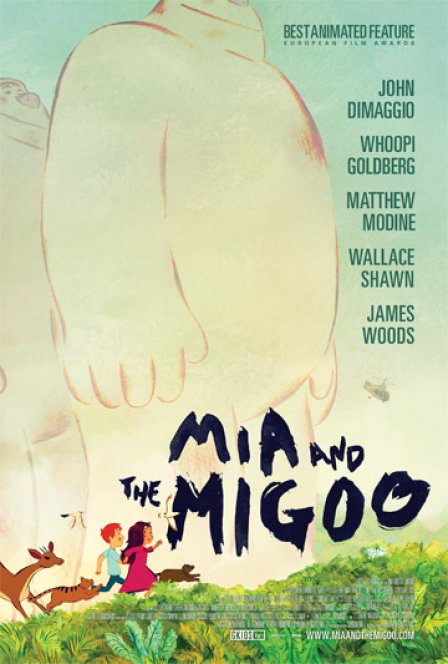

The problem with marketing a French film to American audiences as having “won Best Animated Feature at the 2009 European Film Awards,” but first pitching it to American distributors as “the film that won a European ‘Oscar’ with all-new voice performances by hacky American actors and the guy who does Bender on Futurama” is that the latter sort of cancels out the former.

But while the US version of Mia and the Migoo smacks of pandering, Wallace Shawn and (if only for a brief cameo) Whoopi Goldberg deliver great performances. And the presence of James Woods and Matthew Modine cannot be construed as a creative ‘choice’ by director Jacques-Rémy Girerd; it was clearly some kind of ‘precaution.’ Sure, there’s something unsettling about Woods attempting to play anyone or anything other than himself, but he is fine in his brief role. And while DiMaggio tends to thrive as a voice actor when he’s allowed to play utterly unredeeming and psychopathically evil characters, he does well for his part.

The story is intriguing. DiMaggio’s character, Jekhide (it’s a ‘joke’ — get it?), is a wealthy industrialist/giant man resembling Magilla gorilla heading up a vaguely defined, multi-million dollar, ecologically questionable construction project in the south of France, one that seems to be turning the local waters a sickly toxic orange. When Pedro (Jesse Corti), a worker on the site, is buried alive and left for dead after a tunnel collapse — which may or may not have been the work of meddlesome giant monster-saboteurs that are said to inhabit the enchanted mountain region! — his daughter Mia (Amanda Misquez) telepathically senses his distress and sets out to rescue him.

Having breached the mountains, she meets the Migou (all of whom are played by Shawn), shape-shifting, transmigratory, telekinetically-gifted, absent-minded, cuddly sasquatches, and whom she easily befriends. But around this time, the mad Jekhide and his (unintentionally) cloying and obnoxious son Aldrin (Vincent Agnello) have arrived with a gang of munitions to extirpate the lovable oafs and their live-giving tree once and for all. A given Migou’s inability to differentiate between himself and another is, for the viewer, a constant source of both amusement and confusion, with Shawn infusing his roles with a childlike whimsy that’s alternately funny and genuinely moving. But this holism of identity may also be the key to Girerd’s environmental message, because the Migou’s sole purpose is to protect their source of life: an upside-down tree whose roots are exposed to the open air, a concept open to any number of grim, depressing habitat-in-decline metaphors.

But the single most striking feature of Mia and the Migoo, and perhaps any traditional “2D” animated film of the past decade, is its animation, made up of 500,000 staggeringly beautiful, hand-painted cels, coursing a grand sweeping history of the French visual tradition, from childrens illustration, caricatures, and cartoons, to Cézanne, Monet, and full-blown abstraction. All of this is a real treat when one considers that, historically, the attention paid to the look of animated features was limited by the constraints of money and time. But, within a reasonable period of time, and working primarily with pencil and watercolor, Girerd and his team have crafted a lush, visually resplendent world in no way mitigated by the even peskier ‘precautions’ of mawkishness and aesthetic uniformity: his is a visual universe of free expression.