Sleepovers are some of the most natal and banal activities you can experience in the confusing swamp of adolescence. You lounge about with your best buds, watch a movie, maybe sneak in a beer or two, until you’re left wrapped up in a cocoon of your own warmth. They’re generally pretty chaste and unexciting, and what’s interesting about David Robert Mitchell’s debut film is that it wouldn’t want to convince you otherwise. Rather than attempt to mythologize the sleepover, the director simply posits it as a place to be, a social rite of passage in which not very much happens. And indeed, his characters feel like so much time has passed. They’re always looking, searching, for that special something that perhaps once caught their eye — usually outside their grade level — and to get out of their own cocoons for a bit. The sleepover is simply a means to an end. Your friend’s hot sister is taking a bath upstairs; the stuff of memories is made when you walk into that bathroom.

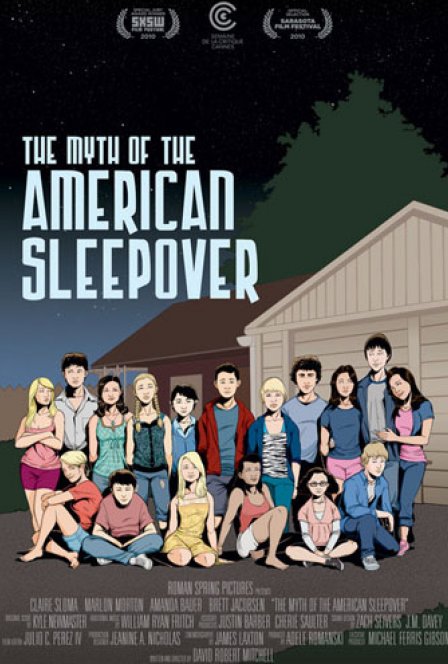

But instead, they just keep looking. As it turns out, this is hardly a film about sexual awakening, despite the tension in each lingering, barely stolen glance. Mitchell’s unhurried pace keeps the film mostly non-confrontational, ostensibly leaving the muddled “confusion” of teenage years to speak for the characters’ listlessness. It’s the last weekend of summer, and there’s a boy that shorthaired blonde Maggie (Claire Sloma) wants to hook up with. Meanwhile, pigtailed Claudia (Amanda Bauer), mildly unenthused with her senior boyfriend, decides to make good on her invitation to a slumber party. Shy Rob (Marlon Morton) can’t stop thinking about a certain blonde girl he sees at a supermarket, while college boy Scott (Brett Jacobsen), home on vacation, remembers his infatuation with some foxy identical twin sisters. As they all head into the night, these intertwined stories all convey a palpable sense of longing and bring their characters somewhat further towards the unknown.

Yet while Mitchell admirably keeps his story within the confines of reality, his world is languid to a fault. The characters end up learning very little, or at least confirming what they already know, and it’s here where this Myth disappoints. In all of its sneaked glances and moments of earnest affection, the movie lacks subtlety; its characters’ pallid, single-minded perseverance becomes less charmingly awkward than dully transparent. Claudia is easily the most mature and compelling character in the film, simply because her baggage is the most concrete: a quick perusal of the party host’s diary informs her that her man is cheating on her. Sitting on the porch in a drunken stupor, she witnesses a hunk emerging out of the dark of the woods, signaling opportunity knocking. This is as mythical as the film gets. One almost wishes Mitchell indulged in a bit more faux-magical realism to shake up the proceedings (though it’s pretty surreal to see Scott not totally weird out his crushes upon confession).

While the film’s narrative progression doesn’t satisfy, the crisp camerawork remains sharply observant throughout. In one scene, Mitchell ends an innocent exchange between a pack of girls and boys, cutting between their post-encounter reflections as they walk in opposite directions. Rob is clearly spinning a few amorous lies to impress his friend, while the girl seems merely to be sharing an embarrassing story about him. Relative truths aside, it’s an evocative juxtaposition, showing how verbal affirmation in gender-specific friendships can sound different but ultimately serve the same purpose: we’re all in this together. Perhaps there is a thing or two to those sleepovers.

Films with similar plots like American Graffiti energetically capture that sense of teenage abandon, where the last day of summer seems very much like the end of the world; but it’s clear here that Mitchell is going for a more general idea of transience that these young characters are learning ever so slowly. In the end, though, we feel less respectful of their naiveté than wanting to throw a cup of cold water in their face. We want them to be dumb, rather than slowly approaching the idea of being dumb. One scene takes place in a make-out maze, where faces are purposely shrouded, for the reason that “you’re not supposed to see what you’re doing.” If only the characters — budding scholars of the teenage gaze — all made good on such risks.