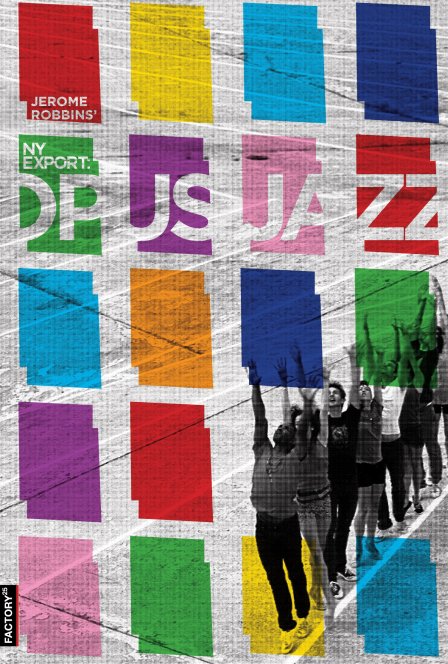

In 1958, Jerome Robbins, already enjoying international fame for choreographing West Side Story, created his “ballet in sneakers.” With this pioneering, bold, and decidedly un-European work, Robbins hoped to capture some of the more interesting and risqué elements of New York City life that Bernstein left out of his Shakespearean masterpiece. Featuring the nuanced and frenetic music of Robin Prince, NY Export: Opus Jazz is essentially a distilled, stripped-down, and rarefied version of everything Robbins found intriguing about his hometown, most especially the brutality and vigor of gang culture and the unbridled sexuality of young urban people with little-to-no money and nothing much to do.

While it’s true to say that an understanding of context and respective cultural norms are absolutely essential components in any rumination on the works of the past, it’s also safe to say that NY Export: Opus Jazz definitely packed way more of a punch upon its release in 1958 than it does now. In Eisenhower’s day, a ballet that featured a dozen or so young people on-stage hypnotically thrusting their pelvises to a frenetic bebop beat could understandably lead to consternation in the stifled audience its creator meant to shake-up. Today, this ballet no longer shocks its audience. Perhaps it’s impossible to experience the same sense of novelty that this ballet was meant to engender, but as a cultural artifact it succeeds in calling to mind the struggles of those whose milieu was a bit more repressed than our own.

G.B. Shaw used to say that dancing was a perpendicular expression of a horizontal desire, and in no place or time does this seem more apropos than in the third movement of Opus Jazz, “Passage for Two.” The movement, an interracial duet set in an abandoned section of railroad at dusk (The High Line Park), features one of the most beautiful and breathtaking representations of coitus you’re likely to see in dance. In 1958, it was quite a scandal. A white girl and a black guy get together, away from their respective social groups, who obviously hate each other, and slowly dance to some of the most plaintive music this side of John Coltrane. The piece, the dance, and the setting all reflect the level of artistry present in the work and those performing it. Watching this and the other movements of the ballet, you get a sense of the absolute joy these dancers take in embodying what is timeless in Opus Jazz.

Inasmuch as it was created to be a celebration of what Robbins thought was unique about NYC, the directors of Opus Jazz, Jody Lee Lipes and Henry Joost, unquestionably picked the right locations in which to shoot. Choosing to stage the movements of the ballet in pre-renovation High Line Park, McCarren Pool, Coney Island, Red Hook, and Carol Gardens was a nod of the hat to quintessentially New York landscapes — culturally significant spaces that continue to inspire, even if some happen to be a little dilapidated.

There is something central to the human condition that NY Export: Opus Jazz is trying to speak to. Prince’s original score and Robbins’ original choreography got to the heart of young New Yorkers’ disdain for the complacency and boredom of the urban 1950s, feeling completely without place in an already too-crowded city. It is easy to find parallels to the feelings of alienation that youth feel today or 50 years before Opus Jazz was written. Bearing in mind the universals that the ballet calls to mind, the film brings everything back to what its makers believe is best about New York, ending with a group of young girls practicing ballet, various shots indicating the cultural exports of the titular city. I could think of no more fitting a representation of this classic work than the one pulled off by the dancers of the New York City Ballet, Jody Lee Lipes, and Henry Joost.