When done right, feminist art can lead somewhere endless. A mutating of roles, ideas, expectations, imagery, even politics that fuck you up something sinister is what feminism is, or at least, should be, about. All too often we are embarrassed by the riches of safe shit, politically correct assumptions masquerading as art that are then lauded for it. Not to mention the inability of those not equipped with a literal vagina to make any art about women: we censor, we frown, we disapprove of those equipped with dicks who may have something to say about femininity. It seems especially confining when it comes to film. When I first saw David Lynch’s Inland Empire (TMT Review) on opening night, my idea of feminist art was completely shattered. Amongst tons of other things, Lynch gave us a phantasmagoric depiction of what it’s like to inhabit that space of femininity and brainspeak. I could think of no other filmmaker, other than Catherine Breillat, currently dipping themselves into that kind of murk. And then I saw Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (TMT Review). Gleefully terrified, I laughed my way through it. I left the theater charged with endorphins. I was ready to fuck. Pornography is easy; humor is not. Von Trier’s ability to translate smut and lust to film with wicked senses of humor and disgust is a lot of fun to roll around in, not to mention the other-worldliness of a film so rooted in mythos that it felt spiritual, beyond. If Inland Empire is the pituitary gland, Antichrist is the g-spot. Who knew men would make some of the most freeing art about women?

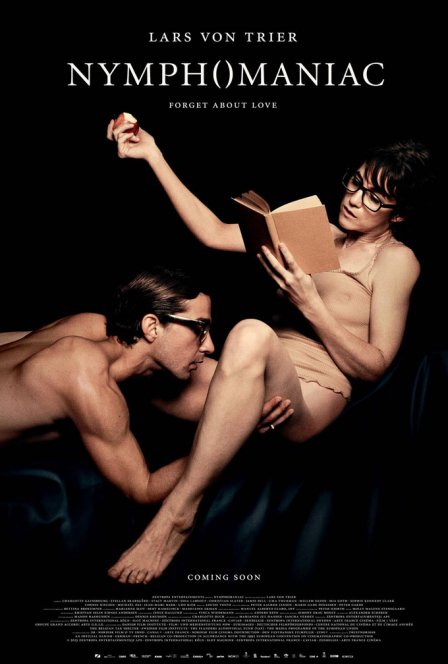

Something like a sexual extension or sister film to Antichrist (there’s even a scene repeated), Nymphomaniac is an operatic orgy of decadent absurdity echoing elements of von Trier’s brand of female sexuality, repression, guilt, and self-hatred. The film’s grandiosity is something to behold. As Antichrist was a witchy romp through visually stunning motifs, Nymphomaniac is a surprisingly thoughtful encyclopedic maze of sex, Bach’s three-part polyphony, Edgar Allen Poe’s delirium, Fibonacci numbers, fly-fishing, and the femininity of cake forks. Wonderfully referential, it is cinematic hypertext, always linking, always breathing an idea into another idea until the rhythm of its jargon becomes a chant constantly wavering between profundity and madness — a narrative quest that is more immersive and haunting moment to moment than it is concerned with any sort of logical, linear plot-line.

The film opens with the sound of dripping water (God bless von Trier’s sound team) and a black screen. We move through a dark alley running with water, snow, little light. Two minutes of nothing but dripping until we’re hit with Rammstein’s “Fuhre Mich” blasting over a shot of Joe (Charlotte Gainsbourg) lying bruised and broken on the street. The thrumming hugeness of this moment is an awesome feeling. Joe is found by Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), a self-diagnosed asexual virgin who has spent his life reading and learning, living alone in a tiny apartment. He offers to call an ambulance but Joe just wants a cup of tea. He takes her to his apartment, and when asked to tell her story, she answers, “It’s long. And moral, I’m afraid.” What follows between the unlikely pair is a four-hour conversation so indulgent in its aura as it’s being created that it’s hypnotic. She starts at the beginning: “I discovered my cunt as a two year old. At an early age I was mechanically inclined. Kinetic energy, for example, has always fascinated me.” From here, we understand Joe as a machine in motion, her physicality a rising and resizing of her capabilities, both destructive and perseverant.

As a teenager and young woman (played by Stacy Martin), Joe’s sense of violence and self-annihilation shifts underneath her attempts at understanding what she is, exactly: A hole? A void? A nothing? She starts a club with other girls, nymphs-in-training, a fucking for the sake of fucking organization that seeks to “rebel against love.” They chant “Mea Maxima Vulva” and forbid boyfriends, monogamy, and fucking the same man twice. “For every hundred crimes committed in the name of love, only one is committed in the name of sex. It was rebellious.” There is a bigger anger here simmering beneath the childish and girlish game of doing the fuck for sport. Von Trier treads lightly in these moments, offering absurdity as an adolescent balm. Seligman laughs — he enjoys the young perversions — but Joe maintains a narrative sobriety, hinting at the edgeless destruction that is to come.

And girl, does it come. At first, it comes from between her legs as she stands “lubricating” at her father’s deathbed (played by an almost comically miscast Christian Slater); and then from her one and only attempt at a relationship with the boy who she politely asked to take her virginity: Jerome (Shia LaBeouf). LaBeouf isn’t half-bad in the film, which is mostly due to von Trier writing Jerome as a bit of a shallow prick, so LaBeouf is fine. Initially, Jerome sees Joe as a conquest, and has no knowledge of her roaring, teething, foaming-at-the-mouth sex drive. Joe knows what he’s trying to do and refuses him, delighting in the ability to make him uncomfortable (i.e. she sleeps with all of his co-workers). We never really quite “believe” their relationship, but who cares — Joe is married to the void of her sex, not to a human being. There is, however, a break: “I wanted to be one of Jerome’s things. I wanted to be picked up and put down again and again.” A handling, a possession, an objectification — this is Joe’s brand of love. What follows next is typical: a relationship, marriage, a child that is born with a menacing smile. And yet the thrust of Joe’s story continues to grow larger than any of these formulaic instances. It’s as if von Trier needs the formula in order to distort it.

What’s next is a quick descent into the filthy, ruined forest of Joe’s adulthood and crumbling cunt. It’s quite a thing to watch the second half of the film bubble out of its cracks and seams with a rancid, oily want that was just beginning to boil beneath the surface of the first half. I don’t give a shit about “acting” anymore, mostly because I don’t really believe in it, but Charlotte Gainsbourg is someone I’d take a picture of to bed with me. She explodes, bellows, breaks herself with a sense of desperation that feels transmutative throughout the second half of Joe’s story. One of Gainsbourg’s most defining moments is in the chapter “The Silent Duck,” in which we watch Joe enter the world of BDSM as a very needy submissive to Jamie Bell’s “Master K.” She is given the name “Fido” and, in the middle of the night, comes running to a fluorescent-lit basement room where she is strapped to a couch and flogged, whipped, spanked, etc., until the skin breaks. One night, she receives 40 lashes (1 more than Christ, as Seligman points out), and her eyes roll back in ecstasy. It’s a simple image, but one rich with familiarity for those of us who have ever demanded a new kind of sexual pleasure that looks more like hate, more like us. I think of Isabelle Huppert stabbing herself in the heart in The Piano Teacher. The end is nigh.

The film exhausts itself with a constant stream of sound, texture, motion, stink, and cruelty until it is left seeping like the open wounds on Joe’s inner thighs. And yet, in the end, it still feels awake, open, like it is doing shit to you even when you leave the theater. I have seen Antichrist maybe four times now, and I can still think back on certain scenes and feel injected. It’s incredible wanting that feeling again from when you first see a film, as it seems more and more rare. Nymphomaniac promises this kind of lurking, too, like it’s going to stick to your insides and grow, taking space on and making you full. “Fill all my holes,” Joe repeats throughout the film as a kind of mantra. A request to plug up an uncontainable body that is as large as a lake, a field, a black hole. Von Trier’s idea of what it’s like to be a woman. And I thank him for wondering.