It was only a matter of time before someone made a movie about Barney Rosset, the man who once said, “I feel personally there hasn't been a word written or uttered that shouldn't be published.”

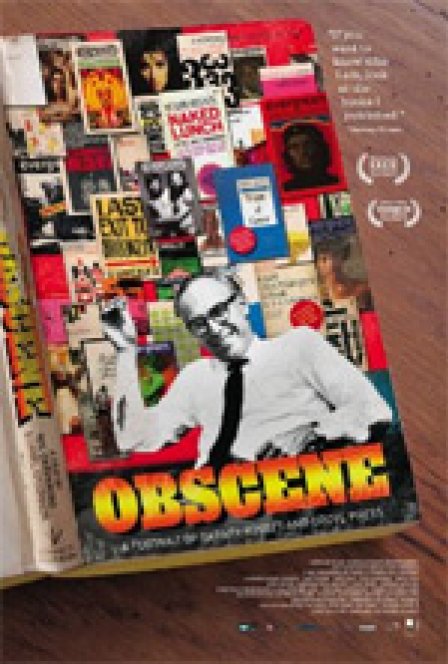

Unsurprisingly titled Obscene, the documentary tells the story of Rosset, who, for over 30 years, headed Grove Press, the publishing house that first brought Lady Chatterley's Lover, Howl, Tropic of Cancer, Samuel Beckett, Tom Stoppard, and Malcolm X to American readers.

Directors Neil Ortenberg and Daniel O'Connor have known Rosset for over 20 years and witnessed his dismissal in 1985 at the hands of Grove's new owners. (Along with a group of investors and publishers, they failed to buy back the company for $10 million.) First-time filmmakers, Ortenberg and O'Connor sought to bring some attention and admiration to their mentor and his work -- so don't expect an evenhanded appraisal.

Rather, Obscene is a loving biography of a man who did, after all, stretch out the straightjacket of 1950s literature. It's delicious watching the hearings on Lady Chatterley's Lover and the army of cultural notables -- John Waters, Betty Dodson, Gore Vidal, Amiri Baraka -- who weigh in on Rosset's career. Particularly moving are the scenes in which Rosset, now 86 and flat broke, sits alone with recordings of a long-ago radio broadcast, his old bones hunched over an ancient tape recorder. Rosset climbing the stairs of his fourth-floor walkup makes for uncomfortable viewing.

The bulk of Obscene, however, concerns the publisher in his prime, fighting the courts to save Lady Chatterley and “the best minds of my generation” and fighting the feminists who bombed his offices. (Rosset maintained they had been hired by the F.B.I.) In the 1960s, he bought Che Guevara's diaries with a suitcase of money and put the famous screenprint of the revolutionary guerilla leader's face on the cover. Rosset also lived on the edge of bankruptcy, losing acres and acres of Hamptons real estate. At one point, he was using 90% of his publishing resources defending Henry Miller in court. “I didn't do that to save humanity,” he says. “I did it to save the Tropic of Cancer.”

Yet there is this nagging question throughout Obscene: why? Why the fierceness about the First Amendment? Given that D.H. Lawrence and Allen Ginsberg are now staples of the English classroom, the filmmakers have less of a battle convincing the audience of Rosset's heroism -- or at least his historical rightness. Even if we are sympathetic, however, we might wonder why they treat Rosset's career path as a foregone conclusion. At one point, he explains, “I would very much have liked to publish Hemingway or Faulkner, but somehow they were already being published.” This can't be the whole story.

But if Obscene is a biography, it is also a chronicle of a cultural era, one in which literature and art and music went a little crazy. To evoke the period, the directors pack their film with the music of Bob Dylan, The Doors, and Warren Zevon, giving the whole show a revolutionary frisson. Animation transitions between the scenes, half television-era Batman, half trippy album cover (although, when it plays under the narration of Howl, the cartoons get a little cheesy). And then there are the books, a mind-boggling list of iconoclastic authors and works that confirm the directors' thesis: Rosset shaped what we read and how we think about art.

Is our anything-goes culture the result of crusaders like him? Perhaps. Are we overlooking a masterpiece today because of a few naughty pages? Perhaps not. Obscene reveals that old saw: one decade's trash is another's treasure.