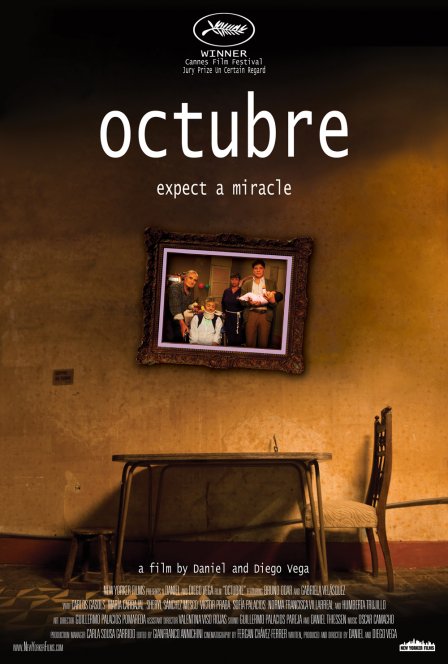

In Daniel and Diego Veda Vidal’s Octubre, the fraternal filmmakers explore the myth of middle-class respectability in modern day Lima. The title derives from the celebration of the Lord of Miracles that occurs in the month of October, with the implication that most residents of the city need a miracle in order to get by each day. The absence of money creates a place in which everyone becomes a criminal or con artist in order to make ends meet in the face of overwhelming poverty. The result is that even those with a good home and the means to enjoy a modicum of luxury acquire such a limited status at the expense of a personal connection to others.

Clemente (Bruno Odar) is a pawnbroker, which, in a society lacking a financial infrastructure, essentially puts him somewhere between a one-man bank, a credit lender, and a loan shark. Clemente himself is about as financially savvy as one can be in this world, though for all the attention he gives to his money, his only use for it seems to be a depressing breakfast of hard-boiled eggs, his TV set, and frequent trips to the local whorehouses. When a baby shows up in Clemente’s apartment, the product of his leisure-time activities, he sets out on a mission to find the mother and return the baby. In the process, he hires his client Sofia (Gabriela Velásquez) to look after the baby. At the same time, Clemente’s own father, Don Fico (Carlos Gassols), a similar master of money and the originator of the family business, blows his retirement savings on a quixotic quest to get his catatonic girlfriend out of the hospital.

Working with a limited scope, the Vidals perform admirably in getting their points across through the three main characters. Although never stating it outright, the filmmakers insinuate that Clemente is reliving his father’s mistakes while ignoring Don Fico’s lunatic attempts to forge a bond with a woman who shows hardly any signs of life. The lack of mentioning a mother suggests that even Clemente himself may have been the product of a brief sexual encounter rather than a happy marriage, just like the baby that Clemente exerts considerable effort trying to abandon. Don Fico’s unexplained attachment to Sofia also serves this general motif of understatement, as though there may have been a similar figure in his past.

Yet for all this subtlety, the Vidals spend too much time constructing their characters rather than simply letting them breathe. Every action is intended to define the protagonists, to clue the audience in on their state of mind. But what might feel like an authentically gritty (although not at all in-your-face) slice of life turns into a modest melodrama. The directors try too hard to squeeze the love story into the portrait they create of ‘middle-class’ society. Still, a complex performance by Oder elevates Octubre. The poignant final shot of him lost among the crowd of those praying for a miracle, having realized he drove away the only “little miracle” life has dealt him, serves as a restrained retelling of Zampano’s primal scream at the end of Federico Fellini’s La Strada.