A Short Homily On 1 Corinthians 13:12-13

For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face; now I know in part, but then I will know fully just as I also have been fully known. But now faith, hope, love, abide these three; but the greatest of these is love.

The New Testament, like the present age, is defined by absent parents: parents who are not parents, and parents who — in absentia — make something of their children. In this way, among others, first century Palestine and 21st century Austria are intertwined.

The gospels, of course, present a curious story about parenthood. For those who are unfamiliar, suffice to say only that a teenage woman is asked to bear and birth the savior of the world. Tradition tells us that it will not be her biological child. The child, himself, will — we believe — see himself not fundamentally in relation to her, but to the heavenly father who sent him. In participating in his heavenly father’s mysterious love — leaving aside for now all theories of atonement — the son is tortured and murdered by the locals. In agony, dying on a cross, he calls out to his father — echoing the cry of the psalmist — “My God, My God, why have you forsaken Me?”

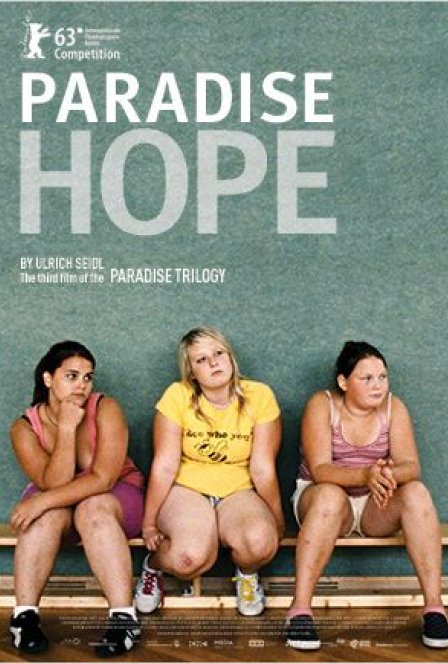

Fast forward, then, to “present day” Austria, in which Ulrich Seidl’s brilliant film, Paradise: Hope, takes place. This is an Austria that, we’ve long since learned (from Bernhard, Jelinek, and Haneke, especially), is struggling to outgrow its shadow, to wane itself from its incomprehensibly brutal past. But Austria, like most western democracies, has simply replaced the ruthless paternalism of fascism with the empty paternalism of experts. No longer do parents need to be parents at all. This is why the children in Paradise: Hope openly mock their parents for befriending them and their friends, for asking permission to buy clothing from The Gap, and even for sending them to fat camp in the first place. The counselors, not the parents, demand discipline, diet, and exercise. Potential mothers, meanwhile, obliviously fuck Kenyans and crucifixes. Thirteen-year-old Melanie, the central (that is, present) figure in Paradise: Hope, is given over by strangers, to strangers. She, unsurprisingly, falls in love with the first adult who treats her like a child. In what appears to be a pedophiliac romance, all that Melanie finally desires is an embrace, that is, to be held, hugged. Instead, she gets only what she forces upon others, or what is nearly forced upon her. And in the end, Melanie is left calling, and leaving a message, to a distant mother who had not yet returned her phone calls. “I miss you,” she says. My god.

While I think Bergman remains our best interpreter of “through a glass darkly,” Seidl is an interesting reader of Paul’s discourse on love in the first letter to the Corinthians. Paul, too, has a different understanding of parenthood, if only because Paul (unlike Jesus, at the time, and Melanie) is on the other side of the narrative: in light of the resurrection, he ascribes purpose to absence. That is, what we don’t see reveals itself in other forms of knowledge. (Think, then, about 1 John, when John equates knowing God with loving, and loving with knowing God.) In previous months, as you hopefully remember, Alex Peterson covered faith and love, undeniably easier themes. (Love, of course, being the “greatest of these,” and faith, no doubt, being the most essential.) Unfortunately, today, I’m left with the difficult task of parsing out hope, that is, hope in a context in which there is none to be found. What does it mean to hope as one who is to live and die in the midst of parental rejection? What does it mean to live in hope when your mom or dad ignores you, and your calls just go to message?

Obviously, there is no meaningful answer to this. It’s cruel to pretend otherwise.

The gospels don’t tell us about heavenly family dynamics. Leave aside all trinitarian conceptions: I’m talking, straight up, about anthropomorphizing the infinite. The gospels don’t tell us how the son reconciled to the father, but only, somehow, that they did. Likewise, Paradise: Hope does not tell us how Melanie is reconciled to her mother, but only that they will be: no camp, save only the most Kafkaesque, is forever. No, all we are left with is the memory of a voice calling out into nothing, for something — something, what’s worse, that’s actually there. I think, in the end, the refusal to deny the silence on the other end of the line is, indeed, its own kind of theodicy, and, even, I hope, a way of hoping beyond hope.