Young-Chan lives with deafblindness even in his dreams. Soon-Ho, his wife, lives with dwarfism.

Young-Chan reads a fairy tale on a device with a Braille keyboard and 32-cell refreshable Braille display. Soon-Ho asks him what he’s reading by fingerspelling on the back of his hands.

Young-Chan takes an exam in Hebrew with Soon-Ho’s help. Young-Chan removes a spent, ring-shaped fluorescent lightbulb and installs a new one under Soon-Ho’s direction.

Young-Chan’s blind and deafblind friends laugh about the funny figurines he sculpts. Young-Chan counsels his young friend that perfect loneliness is preparation for marriage.

Soon-Ho confirms that Young-Chan knows when the train has entered or exited a tunnel. “Mountains must feel lonely with so many holes,” he says.

Young-Chan follows an actress playing deafblind, correcting her movement. Soon-Ho comments that the actress needs to touch a stranger’s body randomly before finding where his lips are.

“All deafblind people have the heart of an astronaut,” Young-Chan writes. I am almost envious of Young-Chan, and I do not admit that my envy is perverse.

With moving patience and apparent imagination, Young-Chan hugs, caresses, and talks to a tree. Soon-Ho tells Young-Chan to throw pine cones at the cameraman; one finds its target.

After discussing death and the possiblity of an end to their interdependence, Young-Chan goes to school without Soon-Ho for a day. After meeting him at the shuttle drop-off, Soon-Ho explains her sensation of feeling colder without him: “Everybody is lonely, I guess.”

“And one is getting old, unaware of the world,” Young-Chan writes. The long history of western metaphysical skepticism is exposed as a frail obsession of the sighted compared to Young-Chan’s haptic epistemology.

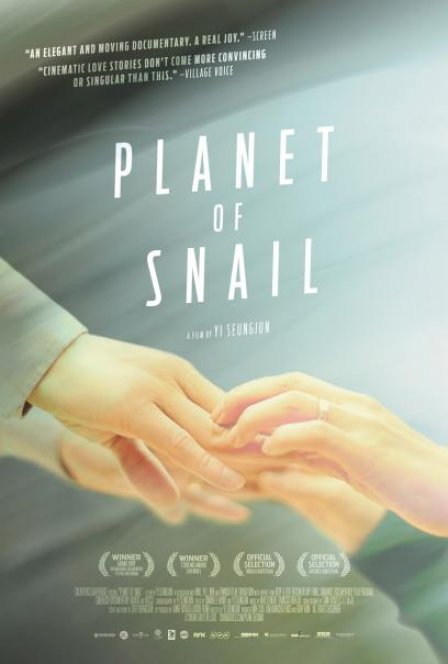

Planet of Snail is a beautiful and beautifully scored film. Strange to think that cinema is perfectly inaccessible to Young-Chan, that the only experience of it he could have would be in description.