Early in The Portuguese Nun, the main character, after discussing what she and her new male acquaintance should do for the rest of the night, exclaims, boldly, “Let’s do as modern life says.” It is this line that rattles around my head more than any other in the film. In many ways, it speaks to what director Eugène Green is trying to do differently with this film, his fourth feature length scattered among a sampling of brilliant shorts. Green has never been afraid to take the piss out of himself and the intellectual stain his films carry (viewers of 2003’s Le Monde Vivant may remember reference to the “Lacanian Witch”), but every joke holds a kernel of truth, and here the director seems to be inching away from the methodical framing and distanced performances that characterized his previous films and allowing, for better or for worse, moments of sentimentality to creep into the fabric of his work.

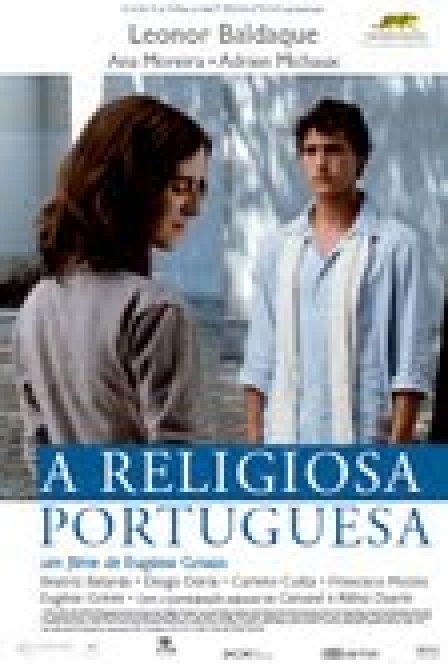

But change comes slowly, which is to say that The Portuguese Nun is unmistakably a film by Green, from first frame to last. The film opens with Julie de Hauranne (Leonor Baldaque), an actress on location in Lisbon to participate in a loose adaptation of Letters of a Portuguese Nun, the now-believed work of fiction in the form of letters from the 1600s generally thought by historians to be written by Gabriel de Guilleragues. Since the film being made is said to be “unconventional” by her director, Denis (played by Green), and because they’ll spend hours shooting around the city with no actors, Julie has the freedom to wander though the city she feels close to, but has never visited. Art mirrors life, and through a series of encounters, most notably with a young local boy and a nun, Julie discovers a purpose and place for her life to go that she never expected.

While a simple plot description of The Portuguese Nun comes off as utterly pedestrian, in the hands of a filmmaker as unique and confident as Green, it’s anything but. The Bressonian distance and humor his films run on — a combination easily misinterpreted as intellectual reticence — here allows for greater emotional impact through simplicity and the opening up of visual space at crucial moments. The location seems to have particularly loosened up the camera, so at moments where Green would normally hold a long shot, he will instead pan or employ an elaborate (for this filmmaker) crane shot that cuts through the simplicity. Another key to this device is the way Green focuses, rather forcefully at times, on the eyes of his main actress. Big, round, and seemingly unable to blink, always looking right at the camera, right at us, effectively breaking up the rigid formalism of the world the film presents. Her eyes speak in silence what is inaccessible otherwise.

What is inaccessible, and sticks in the craw of most viewers, is not sentimental platitude, but a romanticism that’s harder to pin down and ultimately rewarding for that reason; the combination of the objectivity and self-reflexive humor central to his films is something the director has been working toward, most notably in his previous feature, Le Pont des Arts (2004). The optimism these films build up to, moment by moment, seems a reaction to a certain tendency in French cinema, or rather the reception to a certain strain of said cinema. The characters may be lost in the world, drifting from one encounter to the next, but we’re positive they’re forging some kind of path.

But for all the metaphysical back-and-forth, The Portuguese Nun remains a simple film, conveying “big ideas” without branding the words on the filmstrip. This is assured filmmaking — formally and emotionally — and for that itself it must be applauded. That The Portuguese Nun is the work of a director who is still obviously growing is something to be excited about.