The absurd opening scene of Potiche, a new confection from director François Ozon, foreshadows the camp sensibility that will deflate the film’s subsequent hints of seriousness. After a morning jog, chipper housewife Suzanne Pujols (Catherine Deneuve), clad in a goofy red tracksuit, observes with wonder the woodland creatures scampering about her home. The irony is good natured, but it generates neither humor nor sympathy. And while the remainder of the film is more subdued, it unfortunately suffers from the same failing.

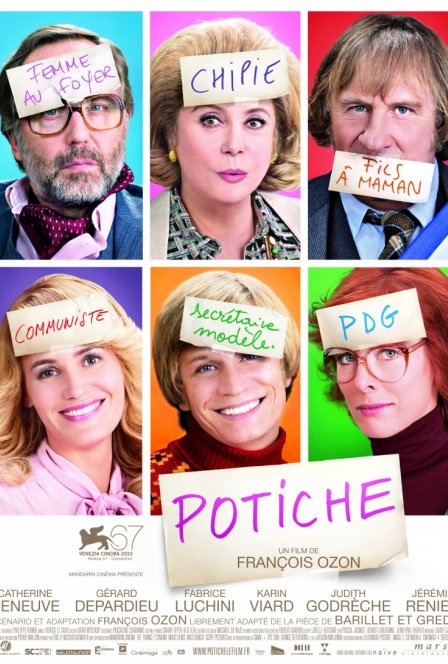

“Freely adapted” from a 1977 play by Pierre Barillet and Jean-Pierre Grédy, Potiche concerns what happens when Suzanne’s husband Robert (Fabricio Luchini), the despotic owner of an umbrella factory, suffers a heart attack and the formerly submissive housewife must step in to run the business. She is aided by her husband’s political adversary — and her old flame — the communist mayor Babin (Gerard Depardieu), who later betrays her. Suzanne’s optimism, goodwill, and common sense result in changes that increase both worker satisfaction and productivity.

Aside from 9 to 5 (1980) — which has a similar plot development — Ozon’s film mostly closely resembles his previous collaboration with Deneuve, 2002’s 8 Women, which also explored feminine roles from a camp perspective. Potiche is more likable, but it’s also blander and less stylish. As in 8 Women, there are moments in Potiche when the characters begin to connect as human beings, but Ozon cues up a score so saccharine it can only be taken as ironic, coming from a director of such studied self-consciousness. It undercuts the performances of a fine cast, in which Deneuve is matched by a comically frazzled Luchini and the bloated but still charismatic Depardieu.

The technique here is arguably Brechtian, but Brecht sought to distance audiences from the characters in order to engage them with the social issues being addressed. Ozon’s brand of camp distances the audience from the characters and the issues. These issues — labor unrest, shifts in women’s domestic and professional roles — are dealt with frivolously. It’s certainly no crime to make a comedy about something serious, but Ozon evinces little genuine interest both in the issues that inform his plot and in producing a farce that’s more than sporadically amusing. In his prolific career, he has been equally compassionate and cruel, sincere and ironic, but here he demonstrates a faux-innocence that he seems to admire but can’t take seriously. It isn’t that he dislikes his characters, it’s that he wants to revel in their artifice, even as his cast struggles to make them real. This makes it a minor film in his oeuvre and a mere footnote in those of its legendary stars.

In the movie’s closing act, when Suzanne runs for mayor against Babin, her naïve optimism transforms into naïve pseudo-populist demagoguery. Ozon actually seems to champion this. Maybe he’s just being ironic, but if he’s not — and I don’t think he is — it’s a strange position to take. I don’t know about France, but in this country, naïve pseudo-populist demagoguery has become a national problem.