You are what you love, not what loves you. —Adaptation

That quote, whimsical and inspirational as it may be, echoed throughout my head while watching Hitoshi Matsumoto’s R100, a gonzo S&M comedy that’s propelled by humiliation, beatings, and other para-sexual acts. It’s hard to say exactly what Matsumoto’s film is about, as the director engages in multiple tactics to both underline and undermine his own points. He breaks the fourth wall, he makes audiences understand the pleasures of submissiveness only to show them lead to ruin, and he provokes laughter and then pity within the same scene. The countless possible readings of this film all depend on what audiences bring in with them, but the one that resonates strongest is the freedom found through submission. Whether it’s submitting to the whims of a dominatrix, to letting a loved one go, or to the insane machinations of an unhinged filmmaker, submission offers an escape for the willing. If you are what you love, then Matsumoto is a man defined by testing boundaries while trying to say something about modern Japanese society.

Takafumi Katayama (Nao Ômori) is an ordinary salesperson at a furniture store that spends most of his time working and taking care of his son, Arashi, while his wife [spoiler alert, but you like the pain don’t you?] remains in a persistent vegetative state. He seeks out Bondage, a multi-national organization that specializes in dispatching dominatrices with a rather unusual premise. Clients sign a one-year contract, and dominatrixes will show up randomly or at an arranged meeting and mistreat the client — who must remain submissive at all times — in unique and bizarre ways. The clients are not allowed to cancel the contract mid-term and in term find new ways to be humiliated and punished that helps them reach a euphoric rush that no other experience offers.

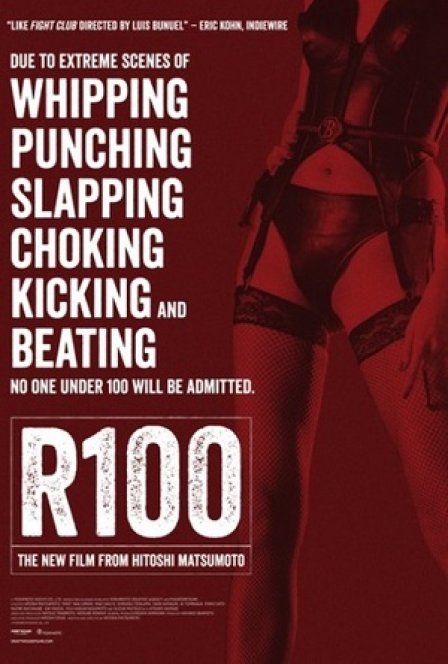

Katayama is soon exposed to all sorts of specialists, each dubbed Queen: the Queen of Voices, the Queen of Gobbling, and, in perhaps the film’s most memorable scene, the Queen of Spitting. But as he is enjoying these increasingly daring and bizarre humiliations, the Bondage club begins to encroach further and further into his everyday life in ways that make him truly uncomfortable. Thus he tries to escape only to be met with renewed resistance from these Queens of Pain. While this is all going on, the film occasionally cuts back to a review board watching the film as we are watching it, trying to figure out how to rate the movie. The director is shown as an ancient man who set out to make a film that would only make sense to people that are 100 years old. (In Japan, R-ratings are followed by the age appropriate for the people to see them, such as R15 and R18; hence the title.)

Katayama’s story isn’t one of a man who learns to assert himself (though he does that a bit, too), nor is it a put-upon man who sublimates a life of hardship into sensual ecstasy (though he does that, too). Instead it’s a man who finds the greatest happiness and joy by giving himself totally over to the whims of another, but still tries to compartmentalize that from the rest of his world. Despite the sexual and emotional fulfillment the sessions provide him, Katayama remains ashamed of his desires, and wants them far away from his family. One scene is a long tracking shot of Katayama entering his house and walking through the darkened rooms to check on his son and reflect on his day before the light switches on and it cuts over to a particular abusive Queen laughing at him and prepared to start a session.

But is our protagonist wrong to compartmentalize? Once Arashi is strung up and gagged, the audience isn’t sure exactly what side we should be on or how to react. Much of the film has comic sequences, and the fourth-wall breaking ratings board voices the befuddlement, but then there are troubling moments that simply occur without commentary on or indication of their emotional intent. It’s hard to figure out just what Matsumoto is saying; that’s the intent. Though none are especially transgressive for anyone with an Internet connection and any knowledge of the kink scene, these encounters are presented as outlets for Katayama, for comedy, and for learning new levels of what one is willing to submit to.

We post “similar films” along with these reviews, but those named above aren’t really like R100. Matsumoto has created a unique work that defies genre, expectation, and various levels of taste. But in doing so, he’s made a brash new film that asks audiences to simply submit to the experience, to see the possibilities in life and the ways we each submit to various indignities throughout it. There’s beauty in our humiliations, things to be gained from our defeats, and joy from giving up entirely. Perhaps that is what can be learned from a century of living, or from a few intense BDSM sessions. Instead of bracing and trying to define what’s happening, perhaps we take the beating and find pleasure. Or maybe the film is just an excuse to watch a heavyset girl in bondage gear dance while spitting food onto a dude trussed up like a steer at a rodeo. Hard to say, really.