There’s something miserably intoxicating about engaging in an affair with an older lover: You know the hourglass sand is falling, grain by grain, until time has run out and one of you realizes it will never work. You learn your lessons in carnality and are expected to apply them to someone more appropriate, someone your own age, someone with whom you have a future. But the sad truth is that no one else will take your hand and show you how it’s done, leaving you breathless and amazed at what can happen to you in the hands of a more mature lover. Falling in love for the first time is itself an intense lesson in human behavior, but falling in love with a 30-something year old when you're much younger brings its own unique revelations. An older lover comes wrapped in a messy package of disappointment, lost loves, cheated hearts, and faded happiness. It’s all too much, too soon -- a young masochist’s dream.

Until you realize that said lover is actually a war criminal and worked a stint at Auschwitz. Hey, it happens.

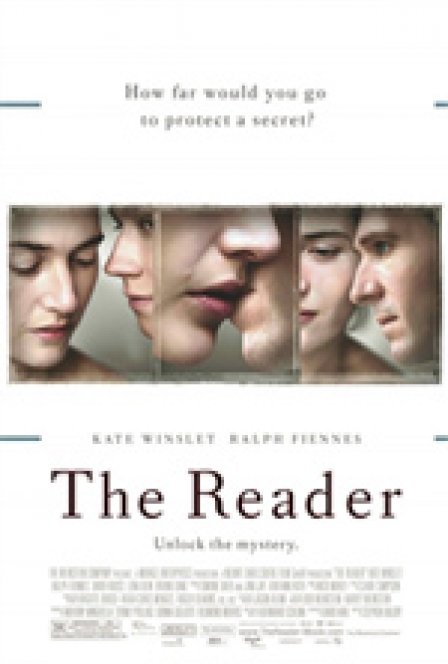

The Reader tells the story of Michael (David Kross), a 15-year-old German youth who has a summertime affair with an older woman, Hanna Schmitz (Kate Winslet). They meet in an alleyway one rainy day as Michael is throwing up his lunch. Although a stranger, Hanna helps the boy home. Michael is diagnosed with scarlet fever and is put on bed-rest. Once he is healthy again, Michael jumps on his bike, and his skinny legs pedal furiously to Hanna’s flat to thank her for her kindness. What follows is abrupt, awkward, and kinda sweet: Hanna takes Michael to bed, setting in motion an affair that is rigged with sadness and desperation.

After they have sex, Michael reads aloud to Hanna. She finds the language he speaks through literature to be both mysterious and exhilarating. Homer, Chekhov, D.H. Lawrence, and other high school-required readings are Michael’s books of choice. He is in love, but we know Hanna is not. She is coarse with Michael, and there’s a hardness to her that suggests a previous life of misery and hardship. But there are also moments of vulnerability and kindness, as Hanna listens to Michael read, sometimes even weeping in his arms. Winslet dominates the role, from her heavy-footed walk, each movement embodying a serious sense of purpose, to her look of stern confusion when Michael asks, “Do you love me?” I fell in love with Winslet all over again at that very moment, as her eyebrows furrowed and a quiet grimace fell across her face, as if Michaeul were speaking in Icelandic. It is an expression that implies love is foreign to Hanna. It’s subtle but significant, explaining so much without the obligatory flashback (unlike Michael’s story which is told completely in flashbacks) or extensive explication. Thank you, Ms. Winslet.

Hannah inevitably ends the affair and disappears from Michael’s life. Michael matures into sideburns and nervous smoking habits as he earns a law degree. His class visits a trial one day, and, lo and behold, there's Mrs. Robinson herself, Hanna, a former SS guard. Michael watches helplessly as she is sentenced to life in prison for her job at Auschwitz. A prisoner testifies that Hanna used to order Jewish children to read to her in the camps, leaving Michael with a twisted feeling of déjà vu and the realization that his ex-lover is illiterate.

And this is where the story goes horribly wrong. The film attempts to draw a parallel between Hanna’s illiteracy and her guilt, suggesting that her illiteracy is an excuse for her moral bankruptcy. But illiteracy isn’t an excuse; it’s a symbolic manifestation of her guilt and ignorance of what was going on in the camps. Historically, it’s also the willed ignorance of the German people. “We had no idea” is the excuse we hear from German citizens forced to walk past camps after the prisoners were liberated by Russian armies.

But director Stephen Daldry never really develops this thesis of willed ignorance, opting instead for the impossible equation of relationship melodrama and mass genocide. Michael and Hanna's relationship in the first 45 minutes of the film was worth a story, but it descends into absurdity when the Holocaust comes between them. It seems like Hollywood is only capable of either exploiting the Holocaust beyond reason (see Schindler’s List, The Boy in the Stripped Pajamas, Life is Beautiful) or turning it into muzak.