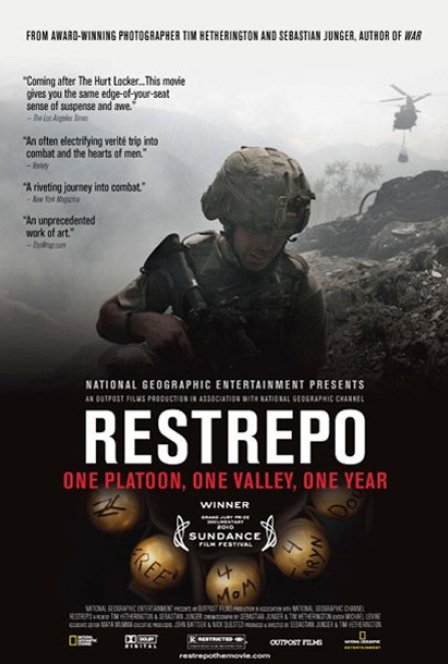

Anything you read about Restrepo will most likely mention its combat scenes. No wonder — it feels as if a bullet might pierce the screen. Directors Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington wield their cameras right alongside a platoon of US soldiers wielding guns of all sorts in the most dangerous outpost in Afghanistan, the Korengal Valley. It’s unnerving to see such raw violence filmed from such a vulnerable perspective. In one scene, a conversation inside an armored vehicle comes to an abrupt stop when it rolls over an explosive device, while the soldiers (and filmmakers) are nearly overtaken by Taliban fighters firing from only a few meters away — moments like these are both incredibly valuable and difficult additions to our understanding of war.

But Junger and Heatherington followed the platoon for over a year, and fighting, it seems, isn’t a 24/7/365 thing. These soldiers play guitar, meet with village elders, dig trenches, fill sandbags, miss their families, wrestle, life weights, and dance to horrible music. They also spend a lot of time being bored. If I really had to chose, it’s these moments, not the fighting scenes, that make Restrepo such an exceptional documentation of modern warfare. In the midst of life-threatening firefights, it’s hard to capture, or even care, about soldiers’ aspirations, emotions, or personalities. While the film’s not long, the directors still manage to take the time to look at how the relatively brief periods of fighting they engage in punctuate the solders’ lives. Really, it’s not combat but loss that gives the film its structure. “Restrepo” was a member of the platoon who was killed before the filming began; footage of him bookends the documentary, and the mountaintop outpost where most of the filming took place was built, and named, in his honor. So, while the cameras never leave the Korengal Valley, it’s hard to say that Restrepo is narrow in its scope.

This attention to the details of soldiers’ lives is, in Restrepo, an end in itself. In that respect, it’s similar to a growing body of film and literature on our other war, most notably The Hurt Locker. The homosocial bonding between the men, especially, is reminiscent of that film. But freed from the conventions of fiction films, where you have to actually craft a compelling story that follows narrative’s — not life’s — conventions, Restrepo does an even better job of separating the experience of war from its clichés, especially the ideological ones. Here, the soldiers don’t have to do anything exceptional; they’re interesting simply because they’re real. More than anything, Restrepo reminded me of Nick McDonell’s recent book, The End of Major Combat Operations, a longform piece of journalism that’s lacking in facts and big on details, like how one soldier “had a plan to move to the beach back in Rio, drink rum, and fuck Brazilian chicks, two at a time, from every direction, balls deep, all day long, forever.” Restrepo has similar talk of banging, and no shit: if you were getting shot at all day, wouldn’t you take comfort in the friendship of your colleagues and daydreams of sex?

Restrepo’s kind of filmmaking is ballsy, but it’s a meaningful stylistic point. Even as the filmmakers claim their movie lacks any political agenda, focusing on the physical texture of the soldiers’ “everyday” lives in Afghanistan is its own politics. These soldier’s aren’t thinking about the absurdity of war, even though the audience might be; they’re too busy burning their own feces and carrying building supplies up a mountain. On the other hand, I don’t remember seeing a single American flag in the film. When the soldiers talk about their thoughts and feelings, patriotism isn’t on the list, either. What is? Their dead friends, how they’re scared, and how they can’t wait to get home and bang their wives and girlfriends.