Hampered by the genius of the Coen Brothers’ recent adaptation of No Country For Old Men — also based on a novel by National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Cormac McCarthy — The Road’s continuously delayed release date served the purpose of spreading what the producers must have deemed necessary distance between the two projects (after all, it is unlikely that the Academy would award Best Film to a McCarthy adaptation two years in a row, right?). Ever since Oprah’s crowning of The Road as an official book club title — an honor that must have inspired a Jonathan Franzen-like cringe — suburbanites have been clamoring for a screen adaptation. As for me, I knew The Road was destined for brilliance after the final scene of No Country For Old Men, when Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) tells his wife about a dream he had of his long-deceased father carrying a flame through the dark and the cold. Bell is sitting at the kitchen table, and as he translates his dream, we notice a painting on the wall of a road curving away into the sunset.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the plot of The Road, here it goes: a major (and mysterious) world catastrophe occurs, destroying life and human civilization. The few remaining survivors fall into three camps: they either (a) roam the countryside for food and attempt to survive until their luck runs out, (b) become flesh-eating, zombie-like drones who travel in packs of suppressed, slightly southern serial killers who are in desperate need of some serious dental work, or (c) commit suicide. A man, his son, and his wife are among the survivors, and when the wife chooses option (c), the man and his son are forced to choose option (a) or risk being caught by those who have chosen option (b).

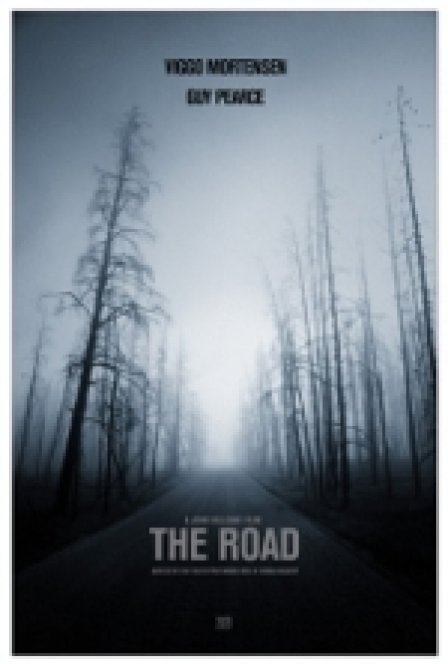

Oprah sure does like her shit bleak. She also likes it mixed with a heavy dose of sentimentality, because her audience is more Rick Warren than Jean-Paul Sartre. Undoubtedly, The Road, McCarthy’s most “tender” novel, explores the relationship between Father and Son as the rest of humankind eats each other. In the novel, McCarthy — who is listed in the film credits as a writer — counterbalances the sappiness of the father-son relationship with a hefty amount of fear and post-apocalyptic paranoia, as murderous cannibals pursue The Man (played by Viggo Mortensen, who pulls off the hunted wet dog look better than anyone else) and The Boy (Kodi Smit-McPhee) through the depths of Appalachia to the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. The Man carries a gun with two bullets. The Boy’s death is a constant thought because of how The Boy will die: will it be Dad behind the trigger or some maniac with sharp teeth? This scenario lends itself to the tremendous love story between The Man and The Boy, and McCarthy challenges the familiar parental love motif by abandoning all hope for survival.

Unfortunately, director John Hillcoat plays down the cannibalism and plays up the paranoia, creating a situation where the outside world is less terrifying than The Man’s inner world. This is a completely backwards interpretation of The Road. The Man is one of the few characters McCarthy has created that retains a solid sense of rationality. The great thing about McCarthy’s other characters — Anton Chigurh, Judge Holden, Lester Ballard — is that they have no sense of rationality, or rather, they make sense in a sociopathic kind of way. And they live amongst us, in the smallest towns, in the desert, in shacks along the highway. They creep under the floorboards and fuck your dead body. In Hillcoat’s version of The Road, I never felt that The Man or The Boy were truly endangered by anything other than The Man’s own paranoia and, in the end, his old age and failing health. Besides, with cannibalistic zombies invading everything from Jane Austen novels to Woody Harrelson’s legal files, I was disappointed to see Hillcoat veer so often from McCarthy’s vision.

Despite the obvious failures of The Road, there are a few small victories, mostly involving the supporting cast. Charlize Theron takes a masterful turn as the aforementioned suicidal “Wife,” and Robert Duvall has perhaps his most significant on-screen moment of the decade as “Old Man,” a blind seer who encounters The Man and The Boy on the road. Fans of the greatest show in television history, The Wire, will enjoy Michael K. Williams as “The Thief,” a man who roams the beach in search of canned peach preserves (though, we all know what he really wants is some of that Honey Nut).

Ultimately, the mediocrity of The Road can be blamed on Hillcoat’s vision. No Country for Old Men succeeded as a film because the Coen Brothers were smart enough to leave most of the novel untouched (excepting the addition of a joke at the expense of a dead dog). Several years prior, Billy Bob Thornton was able to manage a decent adaptation of another McCarthy novel, All The Pretty Horses (though Matt Damon was horribly miscast as John Grady Cole). Hillcoat’s failure lies in his inability to get out of the way and let the true master tell us his story.