“I don’t use a fig to make a pear.”

– Ermanno Olmi

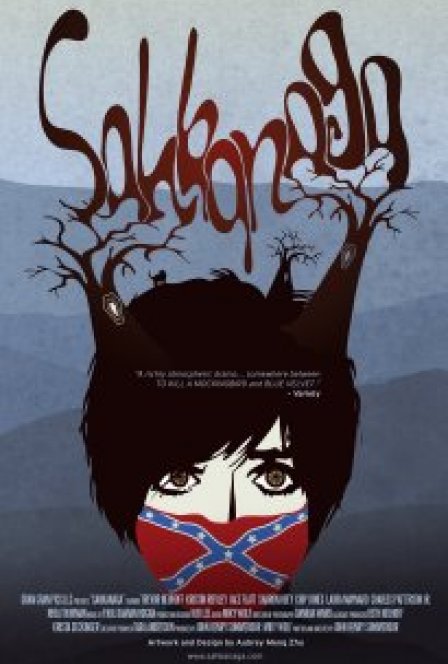

Featuring non-professional actors in a film has always been a fairly risky proposition, fraught with all sorts of potential technical problems. But often enough it yields heartbreaking and/or breathtaking results, so people still do it from time to time. We remember films like Olmi’s Tree of Wooden Clogs and Bresson’s Diary of A Country Priest primarily because these amateur performances have this sublime way of relating the naturally genuine. We tend to forget the unnumbered and utterly failed attempts at verité-by-way-of-featuring-real-people because these films are just too depressing to think about. For whatever reason, it’s vastly more unnerving and embarrassing to watch an amateur fail at playing themselves than a professional fail at playing someone else. Sahkanaga doesn’t ascend to the heights of those aforementioned watersheds of this practice, but taking into account the inherent pitfalls of its method, the film is a fine piece of work in its own right, managing more often than not to transcend the limitations of its cast.

In February of 2002, the Tri-County Crematory in the community of Noble, GA was raided by the EPA, which discovered over 300 bodies in the woods behind the establishment, left to rot in the Georgia sun because the crematory didn’t have the capacity to serve the influx of remains from area funeral homes. The story made international headlines, and the residents of the area are still dealing with the stigma of the ghoulish occurrence. Sahkanaga is an attempt to capture the gravity of that event through the eyes of Paul (Trevor Neuhoff), the teenage son of a funeral director. Paul’s story weaves between coming-of-age, the loss of innocence, and first love, a reach that barely extends the filmmakers’ gasp. The fact that Mr. Summerour grew up in the region isn’t touched upon in the film, but you’d probably be able to guess he did from the intensely personal tone of the film — which honestly makes Sahkanaga that much better.

What’s most remarkable about Summerour’s debut feature is its refusal to moralize the tragedy so central to its action (and his own life). The “villain” of the film, a mild-mannered, helpful sort of man, isn’t treated as an evil or even particularly bad man, just a person who over-promises and under-delivers with a pretty catastrophic outcome. Conversely, Paul isn’t an overly virtuous sort, and can hardly be considered as the hero of the story. Not terribly concerned with assigning blame for the tragic mismanagement of human remains, Summerour is much more interested in how the people of the town handle such a jarring event, and manages to come away with some very compelling, naturalistic performances. The weight of the film exists in part owing to the performances of non-actors, people who actually lived through the story it tells.

Regrettably, Sahkanaga falters when Summerour attempts to tease overt and dramatically resonant emotional reactions from his non-actors. His lingering camera lingers a little too long, and scenes ostensibly meant to depict psychological turmoil come off as forced and awkward, the performers visibly uncomfortable with some of the more drawn out shots. These few missteps aside, the movie is still a compelling rumination on the lingering effects of a gruesome betrayal of public trust, and one which doesn’t require a familiarity with the betrayal itself to be truly appreciated.