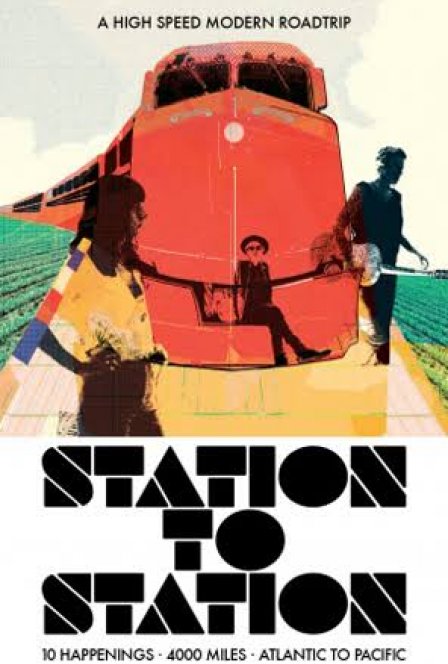

Doug Aitken’s Station to Station is not a narrative film. At least, that’s what Elvis Mitchell kept telling the artist/filmmaker in their discussion following a screening at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art a few weeks ago. Yet debates over whether cinema should tell stories or present a truth in a different form have always been around in some fashion or another. The question really ought to be whether Aitken’s work adds anything to this divergence in film theory. Aitken himself describes the work as 62 one-minute short films about creativity, but this says more about the editing and structure than the subject, themes, or arc. Filmed over the course of Aitken’s train ride across the United States, the work features interviews, performances, and installations with artists, musicians and the occasional randomly encountered individual. Although it’s never stated outright, and often the film incorporates images that can’t possibly have been filmed in sequence, there is a kind of linearity that emerges with each one-minute chapter. The creation of the film coincides with multiple different art “happenings” at stops along the train’s route (hence the title). So in a sense, the film is really a chronicle of a massively choreographed cross-media artistic project. In this respect, it’s certainly a success — there would be little record or reason for these events without the film.

As a stand-alone piece of filmmaking, however, the film never really goes anywhere interesting. Maybe you had to be there at the actual happenings? Perhaps Aitken could have used this to explore temporality in art, the blending of media forms in the digital age, or even something as simple as whether landscape shapes culture. Instead, he tries to delve into the vague notion of modern creativity. Unfortunately, like most discussions with the makers of art, this really never offers more insight than the actual art itself. The film’s revelation is to show how there are different ways of making art and music. Of course, if you have ever walked through a museum or flipped through radio stations, this should be pretty obvious.

This isn’t to say the art or performances are dull in their own right. Sometimes they allow for some captivating visuals, such as the train illuminated in multiple colors of bursting through an over-sized sheet of paper. The cowboy auctioneer who turns his performance into a kind of music or the marching band that performs in an empty warehouse also provide glimpses of American culture we might otherwise miss. Dan Deacon does more to turn electronic music into a worthwhile live performance than pretty much anyone. At the same time, someone like Ed Ruscha has been around since trains were used for actual transit instead of conceptual art. Are we really going to discover something new about his artistic process in 60 seconds or less?

As a chronicle of the larger art project itself, Station to Station provides an interesting yet unsatisfying account (and God forbid anyone say narrative). The images and snippets of conversation offer just enough pith but never enough information. With so many diverse art projects contributing to his conceptual whole, it’s understandable that Aitken didn’t want to do a simple, PBS-style piece. Yet this strands his film between experimental cinema and traditional documentary. He’s not a daring enough filmmaker to do something that stands as an original complement to the overall artwork itself. Perhaps that should have been the last piece, with the artist using his standing to attract a filmmaker with the vision to challenge Aitken’s concept.